The Greatest Unsolved Heist in Irish History

Scandal, conspiracy, and cover-ups in the theft of the “Irish Crown Jewels” from Dublin Castle.

Dublin, 1907.

Arthur Vicars was 45 years old in July 1907, just a few weeks from his birthday. His entire life at the time was wrapped up in his job as Ulster King of Arms. This put him in charge of the rules and regulations regarding heraldry and family trees—a very important position in early-20th-century Ireland: He was the arbiter of inheritance. “Most land, power, and wealth were vested in the hands of the aristocracy,” says William Derham, a curator at Dublin Castle, “and the question of who was the legitimate heir to an estate and a title carried with it the question of who would inherit a great deal of money,” in addition to a seat in Parliament. Vicars, from his spacious office in Dublin Castle, was well paid, well respected, and passionate about heraldic history and genealogy.

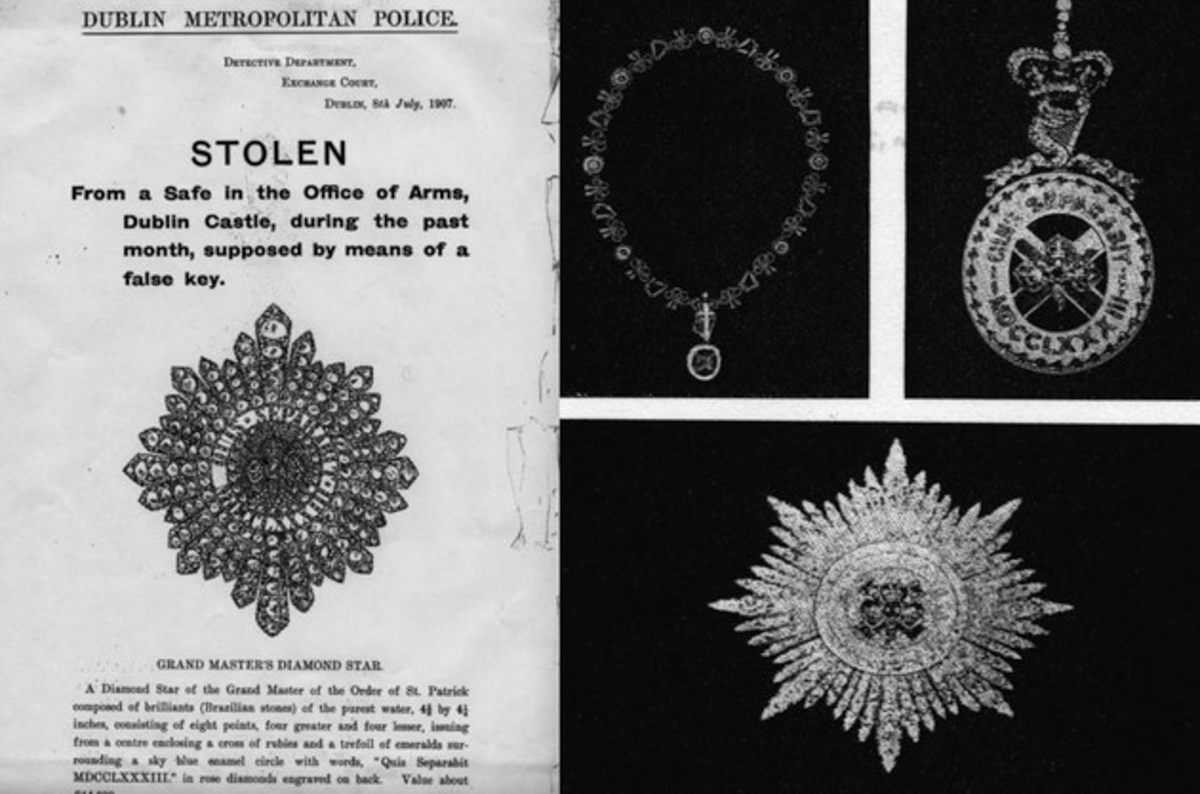

His job also included guarding what would become known as the Irish Crown Jewels, consisting of a heavily jeweled star, badge, and collars. The star, an eight-pointed wonder about four inches across, featured dozens of pristine Brazilian diamonds, described that year as being “of the purest water,” meaning the highest quality known. That star surrounded both a shamrock made of emeralds and a cross of rubies. The badge was similar: diamonds, emeralds, and rubies, set in silver. The value of the pair, according to a police notice, was, in today’s money, somewhere north of £3 million, or $4.5 million. Vicars did not particularly like this part of his job, but if being in charge of these jewels would allow him to continue his heraldry research, he would put up with it.

The jewels mostly stayed locked in a safe at a jeweler’s, in Dublin. That jeweler had been the official watchmaker for Queen Victoria, and valued security tremendously, to the point of counting the spoons they had provided to the royals, to ensure none had been pilfered. If the King, Queen, or their representatives visited Ireland and had call to wear the jewels, they would be moved to a safe that sat in Dublin Castle, an ancient complex that then served as the seat of the government in Ireland for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Dublin Castle was full of military and police agents, as it was the headquarters of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, and the safe in which the jewels were kept had only two keys. Vicars, almost universally described as a pedant and nitpicker, wore one on a chain around his neck or in his pocket at all times. The other he hid in his home in Dublin. The castle, and especially Bedford Tower, where the jewel safe was located, was considered one of the most impregnable, well-defended, and heavily observed buildings on the island. From The New York Times, in 1907: “Bedford Tower is the one building in the castle into which the most enterprising burglar would find it hopeless to effect an entrance unobserved.” And the jewels weren’t even taken out of the safe very often.

The summer of 1907 had been a busy summer for the Irish aristocracy and government, which were often one and the same. The Irish International Exhibition, a grand world’s fair, had opened in May and was scheduled to run through November. The massive event featured a Japanese tea garden and an entire Somali village among hundreds of exhibits, and drew around 2.5 million visitors during its run.

King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, and Princess Victoria were due to visit on July 10, to make an appearance at the exhibition and perform some various royal duties. The political relationship between Ireland and Great Britain was fraught, with a rising tide of Irish nationalism competing with unionists who wanted to remain loyal to the Crown. There had already been debate about how Irish—or British—the International Exhibition should be. (There were separate pavilions for Ireland and Great Britain; the Irish War of Independence would erupt just over a decade later.) On top of that, the king’s nephew, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Prussia, had just months before endured a massive political scandal. King Edward was sensitive to controversy. He needed this visit to go smoothly.

It did not go smoothly.

Four days before the king was due to arrive in Dublin, the jewels went missing. The story of this theft would eventually involve a sex scandal, conspiracies that pointed the finger at both sides of the political spectrum, the occult, drunken pranks, bankrupt celebrities, sham trials, and an incredibly effective hush campaign from the top rung of the political ladder.

The jewels have never been recovered.

The Target.

The Irish Crown Jewels were not really referred to as the Irish Crown Jewels while anybody still knew where they were. That name was given to the collection afterward, during the wild media coverage of the theft. They were technically Irish crown jewels in that they were jewels, in Ireland, owned by the Crown, but they were not quite like the English equivalent, which are worn at coronations.

Instead, the Irish Crown Jewels were an insignia of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, the most important chivalric order in Ireland; they were worn by the most important person in the Order, which was usually the sovereign, at the Order’s most important ceremonies. A members-only club, founded in 1783 with the English sovereign as its head, it was made up of the highest-ranking members of the Irish aristocracy. Most importantly, it was a pro-unionist group, and support of the Crown and its policies was a prerequisite for membership.

The insignia was crafted in 1830 at the order of King William IV, who provided the stones from the collection of his mother, Queen Charlotte. (Some of Charlotte’s other jewels found their way into the Crown Jewels of England, as well. She had a lot of jewels.) So the Irish Crown Jewels were important as a symbol of Ireland’s place within, and as a part of, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The first decade of the 20th century was a time when the future, at least the political future, was slowly coming into focus. This is prior to the Troubles, but the major political players all knew that Ireland was headed for a major reckoning about its identity. “There is definitely a change in the air,” says Shane Browne, a historian at University College Dublin who just finished his doctorate, focusing on Ireland during the period around World War I. The island had yet to fully split or radicalize into those seeking independence and those wanting to remain part of Britain; instead everyone seemed to be kind of leaning in one direction or another, but hesitantly. The nationalists, who wanted more autonomy, weren’t really seeking full independence yet, but instead advocating for home rule, in which Ireland would remain tied to England, but would have its own Parliament for domestic policymaking.

That said, it was becoming clear that the conflict was accelerating. Irish cultural movements were burgeoning; in 1904, Gaelic was successfully included in the Irish school curriculum. The first iteration of Sinn Fein was founded in 1905, on the nationalist side; on the unionist side, the Ulster Unionist Party began importing guns in preparation to fight against home rule, starting on a large scale in 1910. The Ranch War, in 1906, was a major protest by the agricultural lower classes against landlords who controlled the agricultural land, and the issue of landowning equity is as obvious a signal of an independence movement as any (see: Cuba, India, South Africa, and dozens of others). Once landless workers, or poor smallholders, start demanding to be able to own land, the writing is pretty much on the wall.

In response, those in power were treading very, very carefully. Even the Irish Members of Parliament, who were mostly major landlords themselves, started talking about land reform. The jewels, as a somewhat multifaceted symbol of Ireland and Britain, were a tantalizing target.

From 1831, when the jewels were delivered to Dublin, until 1903, they typically resided at West and Son, a prominent Dublin jeweler. But when they were needed, most often during the “castle season”—a couple of months of balls and events—they would be transferred to Dublin Castle. When they weren’t being worn, they were stored in a wall safe in the castle’s Bermingham Tower, in the office of Arthur Vicars’s predecessor. But Vicars decided to make some changes when he took over.

The Location.

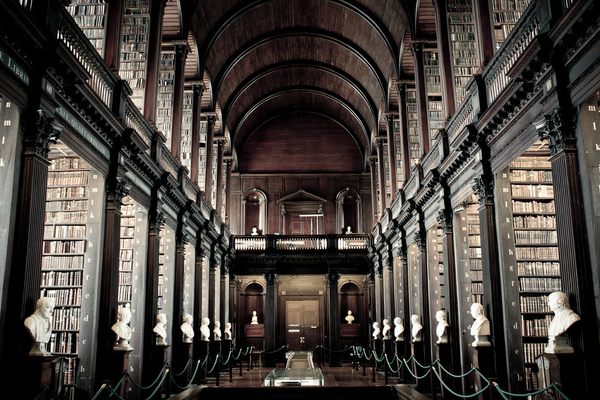

Around 1901, it was decided that the office of Ulster King of Arms would be moved deeper within the complex of Dublin Castle, from Bermingham Tower to Bedford Tower. Vicars, according to the excellent 1967 book Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown Jewels, was delighted at this possibility. He proposed that he should get a (free) apartment in the new building, and also that the safe holding the jewels should be housed in a strongroom. The Board of Works at Dublin Castle didn’t give him that free crash-pad, but it liked the idea of a strongroom that could hold the jewels as well as the castle’s collection of valuable manuscripts.

This tale is about equal parts comedy and high drama, and the comedy comes first. The workers who renovated the new Bedford Tower office went to move the safe into the brand-new strongroom, but found that their measurements were all wrong. The safe wouldn’t fit through the doorway. Bonk. Having already endured months of renovations and faced with the possibility of having to knock down walls to fit the stupid safe through the stupid doorway, or having to go through tons of stupid red tape to get a stupid smaller safe that would fit through the stupid doorway, Vicars and the Board of Works decided enough was enough. They opted to place the safe in the library, with a sentry outside. This would just be temporary until they figured out a solution to the doorway problem. Besides, the heavy safe wasn’t going anywhere, and it was designed to be burglar-proof anyway, according to correspondence from the Chairman of the Board of Works.

In 1905, Vicars wrote some revised statutes for his office, which included stipulations that the jewels must be kept in a safe, which must be kept in a strongroom. Vicars seems to have been extremely passionate about heraldry and sort of annoyed that he also had to guard these jewels, and he never got around to actually moving the safe from the library. This was a problem. Francis Bamford and Viola Banks, the authors of Vicious Circle, describe Vicars during this time as “a completely happy man existing upon the very edge of a volcano.”

The library in question wasn’t exactly tucked away. It was also the waiting room for Vicars’s office, which meant that there was a steady stream of visitors hanging out in the same room as the jewels. The library also had several doors, not all of which were guarded, and the sentry could not actually see the safe from where he was stationed.

The Heist.

In summer 1907, security at Bedford Tower experienced a series of escalating incidents. They were all ignored.

On June 28, Vicars discovered that his key to the front door of Bedford Tower was missing; a guard had to let him in. On July 3, one Mrs. Farrell, who cleaned Vicars’s office, found that the front door was unlocked. She told the sentry, who told Vicars. Vicars did nothing. He did not check the safe, and he did not ask a locksmith to change the locks. This was considered rather unusual for a man who known to be prissy, particular, and detail-oriented.

On the morning of July 6, that same Mrs. Farrell, on her morning cleaning rounds, found that the outer door to the strongroom—the one that didn’t contain the jewels—was unlocked. The inner door was still locked, but not very well—the key was still sitting in the lock, on a ring with other keys, to bookshelves and printing presses in the building. She wrote a note for the sentry, whose name was Stivey, and left the keys for him. When Stivey read the note, he took a look around the strongroom, found nothing amiss, and waited for Vicars to come into work to tell him what had happened. Vicars, still stressed about the king’s upcoming visit, again took little notice, and proceeded up the stairs to his desk.

Later that same day, a messenger arrived from West and Son. They had been doing some alterations to one of the gold collars used by a member of the Order of St. Patrick, which was normally stored in the safe with the Crown Jewels. The completed piece was ready, and the messenger was delivering it. Vicars, absorbed in his work, handed Stivey a key and told him to go down to the library and place the gold collar in the safe.

Stivey placed the key in the lock and was confounded: The key would not turn in the direction he expected it to. He turned the key the other way, and tried the handle. The safe wouldn’t open. It was locked. Realization came to him. If turning the key that way had locked the safe, then that must mean that before he arrived …

Stivey raced up to Vicars’s office and told him the safe had been unlocked. Vicars followed him to the library, opened the safe, and found that nearly everything was gone. All of the gold collars worn by all of the Knights of the Order of St. Patrick. Gone. A case containing a bunch of jewels owned by the Mahony family, into which Vicars’s own mother had married. Gone. The Irish Crown Jewels. Gone.

Well, not entirely. There was a ribbon.

The Ribbon.

The badge of the Irish Crown Jewels had a very small hook on it that was attached to a sky-blue ribbon. The ribbon was mounted on the hook by a clasp, fastened with two very small and finicky screws. A thief could simply have yanked the badge out, most likely breaking the clasp, but who cares about a ribbon clasp when you’re stealing a jeweled badge worth millions?

But the ribbon was still in its box, in the safe. It had been carefully unscrewed and removed from the badge. Vicars estimated that this task could not have been done in less than 10 minutes; he was likely exaggerating, but it certainly would have required some effort. In addition, all of the tissue paper and cloth holding the various jewels and valuables had been refolded and placed back in their boxes. This was no smash-and-grab job. It was downright fastidious. Why would a thief take that much time, and that much care, in the middle of committing the biggest heist in Irish history up to that point?

The Keys.

Vicars immediately called the Dublin Metropolitan Police. They found that the doors to the front door of the tower, the strongroom, and the safe had not been forced, and had none of the tell-tale scratches that would indicate a hastily copied key. It would have taken a few days to make a proper key, but that was one of two possibilities. Either the locks had been opened by professional copies, or someone had the original keys.

There were seven keys to the front door of Bedford Tower, held by Vicars, Stivey, Mrs. Farrell, and a few others who worked in or around the Office of Arms. There were four keys to the outer door of the strongroom, two keys to the inner door, and two keys to the safe. All keys within each set were identical.

Of the four outer strongroom door keys: one each to Vicars, Stivey, one of Vicars’s assistants (his nephew, Pierce Gun Mahony—cool name), and Vicars’s secretary, though that one had been given back and placed in the strongroom.

Of the two inner strongroom door keys: one in Vicars’s office upstairs, and one that was habitually kept in the door lock itself, except when Stivey left his post, at which point it was placed in a nearby drawer in case staff members needed to access the strongroom and its manuscripts.

But, as we recall, the safe wasn’t in the strongroom, anyway.

Of the two keys to the safe: one Vicars carried on his person at all times, and one he had hidden in his house, under some uninteresting papers, in a bookshelf drawer.

The Investigation.

Upon the discovery of the theft, the king’s visit to Dublin Castle was postponed. He was furious. “Politically it was a huge embarrassment. These things were emblematic of British rule in Ireland,” says Derham. “So their loss became symbolic of the disappearance of the British reins of Ireland.” A reward for £1,000—around $140,000 today—was issued. It was never claimed.

The Dublin police began an investigation but got nowhere, so the big guns were called in: Scotland Yard. An inspector named John Kane arrived on July 12. After his investigation, he sent to the Dublin police a report identifying who he thought had committed the theft. Kane was himself Irish, and he was convinced that it had been an inside job. He was particularly obsessed with the sky-blue ribbon.

Kane’s report was roundly rejected by the Dublin police, and Kane and his team were sent back to London immediately. The report has never been found. Newspapers at the time declared this an obvious indication of a cover-up: Kane had found too much, an answer that was unpalatable to those in power, so he was taken off the case.

Vicars, during this time, maintained vehemently that nobody on his staff would have done such a thing, and that the Crown Jewels might well show up on their own. The substantial reward, as might be expected, led to plenty of tips—and plenty of dead ends. One went directly to Vicars himself: A woman working at the exhibition sent him a letter stating that her daughter had had visions about the theft. Vicars was intrigued, but sensitive to the weirdness of the optics. He asked his good friend, Francis Shackleton, to contact her and set up a seance.

At the seance, Vicars was told that the jewels had been buried at a cemetery in a small town outside of Dublin. The spiritualist was not perfectly clear; her instructions could have applied to either of two cemeteries. Vicars eagerly traveled to each, and dug around several tombstones. No jewels were found, but the story did make it into the press, making Vicars a greater subject of mockery than he had already become.

The Staff.

Arthur Vicars had three assistants—suspects, or links to suspects, to all those following the proceedings in the papers—in addition to Stivey and the cleaning staff. These positions were unpaid and largely honorary, though they came with lofty and incomprehensible titles—and access.

The Charmer

Francis Shackleton was the brother of Ernest Shackleton, who was a mega-celebrity in Britain at the time for his voyages to the Antarctic. Francis was an incredibly charming man, handsome and clever and witty, and operated as a man-about-town in the upper echelons of both Dublin and London society. He was a stockbroker of sorts, but it’s unclear whether he was actually good at it. He had gone bankrupt at least once. Partying seemed to interest him more.

Shackleton spent most of his time in London, but he did come to Dublin sometimes, and had an arrangement with Vicars to stay at his house. In fact, despite only spending a month or so per year in Dublin, Shackleton paid half of Vicars’s rent and bills. “It was assumed it was just because he could afford it and liked throwing his money around,” says Derham.

Shackleton was also widely known to be gay, at a time when it was completely taboo in Irish society, not to mention illegal. But, says Derham, “You can get away with most things if you have money. He was pleasantly humored in polite society.” Shackleton’s lover was a man named Captain Richard Gorges, whose service in South Africa was described as violent, bullying, and criminal by an Irish Member of Parliament. Gorges, as a somewhat prominent military man, would have been known to the security forces at Dublin Castle.

Also in Shackleton’s social circle was Lord Ronald Gower, an aristocratic sculptor and biographer who had been implicated in a raid on a male brothel in 1890 and who is generally believed to have been the inspiration for a few of Oscar Wilde’s characters. Another was John Campbell, the Duke of Argyll, who was heavily rumored to be gay as well, and who was, definitively, the king’s brother-in-law. Shackleton was connected.

The Ally

Pierce Gun Mahony was the son of Vicars’s half-brother. A decade younger than Vicars, Mahony belonged to a very old and very wealthy Irish clan, which allowed him to live a life of leisure. Vicars and his half-brother, Pierce’s father (also named Pierce, though he spelled it Peirce), were close despite their differing politics: Vicars was a unionist, and the elder Mahony an ardent nationalist, who served in Parliament.

As a favor to his half-brother, Vicars gave his nephew this honorary position, which would confer some status within Dublin society. The younger Mahony had few responsibilities, but felt a great deal of loyalty toward Vicars for the gift of this job and title (his was “Cork Herald”). An earnest young man, Mahony spent much of his time in England, but still spent more time in the office of the Ulster King of Arms than Shackleton did.

The Wild Card

Francis Bennett-Goldney was descended from a line of antiquities scholars, which made him very wealthy as well. His family collection, expanded upon by his own purchases, was impressive. He eventually displayed much of it in a museum in Canterbury. Bennett-Goldney ended up the Honorary Director of the museum as a result of his donations and activity, and moved to Canterbury, where he joined the town’s upper echelons. He was elected to the town council, then became mayor, and eventually was elected to the House of Commons.

Bennett-Goldney was an ambitious and direct man, used to getting what he wanted. He met Vicars in 1905 at a meeting of antiquarians. Vicars was really only interested in antiquities as a means to learn about heraldry and family trees, while Bennett-Goldney was more of a generalist. He outright asked Vicars for a position within the office of the Ulster King of Arms. Vicars, a little put out by the aggressiveness, asked for a proper recommendation, which Bennett-Goldney, thanks to his aristocratic connections, could accomplish easily.

The Duke of Bedford supplied the recommendation, but it took a while for Bennett-Goldney to achieve his position (“Athlone Pursuivant”). A change in the position of Lord Lieutenant, the king’s representative and in some ways the highest-ranking position in Ireland, delayed Bennett-Goldney’s appointment. He was officially sworn in in May 1907, just two months before the theft.

He also possessed a secret, which nobody would discover until his death.

The Aftermath.

Following the theft, the king demanded that Vicars resign his position as Ulster King of Arms. Vicars refused, saying he had done nothing wrong, and blamed the Board of Works for their screw-up with the whole safe-is-too-big-for-the-doorway fiasco. Vicars wanted his story to be heard and to defend himself in as public a venue as he could create. He asked for a Royal Commission, a trial in which he could call witnesses and defend his good name.

He was refused this, and instead given a sham Viceregal Commission trial, which allowed no witnesses, barred the public and press, and took as its mandate not an investigation of the crime, but of Vicars’s performance of his duties. Vicars and his lawyers, upon hearing these terms, silently stood up and walked out of the room without a backward glance.

Without his presence, the Commission found Vicars delinquent in his duties, based on the statutes he had himself written in 1905, including the one that stated that the safe must be located in the strongroom. Because the safe remained in the library, Vicars had failed in the duties he himself had set out. He was fired.

But rumors had begun swirling, and had reached the new Lord Lieutenant, Lord Aberdeen. Mahony, Vicars’s nephew, was all in on defending Vicars, and used every tool at his disposal. He reached out to Members of Parliament he knew. When Mahony asked why they declined to help, he was told that Vicars was known to have associated with men of “undesirable character.” Eventually, Mahony learned that this Member of Parliament wasn’t the only one who knew about Shackleton and his friends. The king himself knew.

The king, Aberdeen, and their cronies were already hard at work to make this story go away, which seemed to take priority over recovering the jewels. This crew offered Vicars a full pension—a strange move after firing him for negligence—but only if he would stop asking for a public trial. And they also put the pressure on Irish newspapers not even to hint at the possibility of a sex scandal within the Irish government.

They were remarkably effective at erasing any mention of homosexuality from the Irish press, but the Irish-American press was more free-wheeling, and widely read among the Irish diaspora, which would become extremely influential in the Troubles, especially via funding. The Gaelic American ran a bombshell story in July 1908 stating that Shackleton and his crew “were men suspected of unspeakable and disgusting offences.” The story also repeated rumors about orgies involving government officials at Dublin Castle itself.

One reason why King Edward VII was so unnerved by these rumors was the Eulenburg Affair, a massive scandal in Germany in 1906 and 1907. The German journalist Maximilian Harden, a fierce critic of Kaiser Wilhelm II, repeatedly accused several members of the Kaiser’s cabinet and social circle of homosexual acts. The scandal was named for one of the accused, Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg. He, like Shackleton, was deeply involved in the spiritualist and arts communities, but Philipp also happened to be the Kaiser’s closest friend. Accusations bounced back and forth—McCarthyish—and many in the Kaiser’s inner circle were forced to resign. Wilhelm was King Edward’s nephew, and although Edward hated Wilhelm and probably enjoyed his struggles, he absolutely did not want to suffer a similar scandal himself.

More news began to trickle out. Mahony sat down with the publisher of a newspaper for a nice luncheon, and told that publisher a story. Vicars, he said, was a legendary lightweight of a drinker. The parties at Bedford Tower weren’t orgies, he explained, but rather wholesome pranks.

At one of these parties, said Mahony, Vicars got so drunk that he passed out in his office. His drinking buddies got themselves an idea. They rifled through his clothes and found the keys to the safe. Then they went downstairs to the library, opened the safe, took out the Irish Crown Jewels, tiptoed back upstairs, and replaced the keys where they had found them.

It had been a prank, not a theft. Vicars would have gotten quite the surprise, a few days later, when he got a package in the mail containing the Irish Crown Jewels. This might explain why, for at least a week after the real theft, Vicars maintained that it was all no big deal, and that the jewels would just show up.

Knowing this, the newspaper writers said, is it so hard to believe that somebody could have swiped the key to the safe for a real theft?

Like all scandals, even ones this monumental and implicating, it soon began to blow over in the Irish and Irish-American papers. The New York Times ran many stories, mostly little updates on the latest gossip, including the suggestion that the British government was hushing up the crime for fear of scandal. From a 1912 article: “One of the most powerful means for fostering crime in high places was the boycott placed upon its exposure by the legitimate press. Any crime among the poor was paraded and magnified, but the character of the wealthy and official class was treated as sacrosanct, and any word infringing upon it was ruthlessly suppressed.”

The government’s tactics eventually worked. The stories faded out of the headlines. The reward was never claimed. The tips became increasingly preposterous. And the jewels remain missing, over a century later.

The Theories.

With no prosecutions, no confessions, and no jewels, historians and conspiracy theorists have created many different constructions of what may have happened. These come from a wide variety of sources: newspaper articles, a few books, whispers among historians. Some are trustworthy. Some are transparently not. Some are both.

Theory I

Francis Shackleton plans the theft. He always needs money, is regularly borrowing from and failing to repay his rich friends, and lives an expensive lifestyle. He testifies that in 1907, he was so broke that he had to borrow money from a loan shark. He knows that the jewels are fairly easy to steal. Shackleton somehow gets one of Vicars’s keys and makes a copy, and he does have access to Vicars’s house, where the second key sits. He then goes out of town to London, making it a point to meet with London aristocracy to cement an alibi. His lover, Gorges, commits the theft, as he is able to get in and out of Dublin Tower without suspicion, thanks to his military background. Shackleton instructs Gorges to make the theft look obvious by leaving doors open and such, so that the time of the theft is clear and his abili rock-solid. (That didn’t work; the theft could have taken place anytime between June 11 and July 6 because of how rarely Vicars carries out his guard duties.)

Shackleton then breaks the Crown Jewels apart—popping out jewels and melting down the metal—for anonymous sale in Antwerp or Amsterdam. This, some believe, was the conclusion of the report from Kane, the Scotland Yard inspector. But the king and his cronies, fearful of scandal, allow him to get away with it. Kane is sent back to London, while Shackleton is too politically radioactive to be the subject of a public trial.

Theory II

Shackleton is blackmailed. His homosexuality is widely known in polite society, but that is very different from, say, a scandalous article being published in a newspaper, as he relies on a delicate balance of silence, risk, and elitism to survive. In exchange for Mystery Thief/Blackmailer’s silence, Shackleton uses his access and knowledge to procure one of Vicars’s keys, but does not participate in the crime beyond that. He does his best to help Vicars track down the thief. His seance might not have been particularly helpful, but it is earnest.

The king and his cronies hush up the theft owing to Shackleton’s involvement.

Theory III

A clique of unionist officials steal the jewels to embarrass Lord Aberdeen. Aberdeen is a known nationalist and advocate for home rule. The unionists fear that home rule would result in Catholic dominion over Ireland. As Protestants, they are the minority, and do not wish to be treated as such; they are also pretty happy with the status quo, being landlords and other upperclass folk, and don’t want things to change.

To deal with Aberdeen, they hatch a plan to steal the Crown Jewels, which they hope will result in his dismissal for poor management of Ireland, and in turn taint the entire concept of home rule. (This does not work; Aberdeen is not blamed.) Perhaps they blackmail Shackleton into obtaining a key. Perhaps Vicars provides a key, as he also is a unionist.

What happens to the jewels afterward is unimportant to the unionists, as they don’t need the money and can’t risk being caught selling them. Maybe they place them in a security box at a bank, where they remain there to this day.

Theory IV

A group of nationalists want to embarrass the king and demonstrate what a farce English rule over Ireland is. To do this, they plan to steal the Crown Jewels, an Irish treasure that is only worn by the English, and a symbol of the king’s power.

These nationalists steal the jewels, again perhaps by blackmailing Shackleton. The plan, effectively, works. The king is suitably embarrassed, the tide of Irish nationalism continues to rise, and the Crown’s management of Ireland is questioned. The jewels, probably, remain intact, somewhere, in a safe place.

Theory V

Bennett-Goldney is—according to several reports—a thief, a fact that was not discovered until after his death. While preparing the late Bennett-Goldney’s belongings for auction, ancient manuscripts purloined from the city of Canterbury were found in his house, along with a fairly valuable painting. Only Bennett-Goldney could have taken the manuscripts, owing to his privileged position as mayor. His interest in antiquarian objects did not respect legal boundaries.

So then, perhaps, Bennett-Goldney obtains the key, either by himself or with the aid of Shackleton. He creates an alibi, heads out of Dublin, and orchestrates the theft, just a few months after joining Vicars’s crew of honorary assistants. Perhaps this is done with the aid of Shackleton and Gorges, perhaps not.

Bennett-Goldney is not generally suspected, as he has an airtight alibi and is also known to be quite wealthy and not in need of cash. This allows him to subtly steer the investigation. His remarks to detectives are coy and ambiguous, but point them to Shackleton and his sexuality.

In fall 1907, Bennett-Goldney, according to a 1999 history called The Magpie Tendency, had an oddly large gas tank affixed to his car, just before a road trip to Amsterdam, one of Europe’s biggest jewel markets. He traveled there with his friend, J.P. Morgan, who is also believed to have been involved in art and antiquities theft. (Morgan would, in 1911, be questioned in connection with the theft of the Mona Lisa.) Bennett-Goldney may then have sold the jewels into the anonymous stream of Dutch commerce.

Untimely Ends.

None of these theories has really gained traction over another, in large part because the jewels, or any other pieces of incriminating evidence, for that matter, have never been found. Some of them have major problems. Theory III, for example, might have backfired spectacularly. Theory V relies on an awful lot of Canterbury town hearsay found in a book that was self-published 90 years after the theft.

Even though none of the characters in this story were actually convicted, or even tried, for the theft of the Irish Crown Jewels, disaster seemed to follow them.

Francis Shackleton declared bankruptcy in 1910, owing the truly astounding amount of £85,000, well over $10 million in today’s money. He fled to Portuguese West Africa, but was there accused of cashing a widow’s checks, sent back to London, and sentenced to 15 months of hard labor. In 1913 he was charged with conspiring to steal hundreds of thousands of dollars from his old friend, Lord Ronald Gower, by purchasing “stocks” that didn’t exist and pocketing the money. He changed his name, moved in with his sister, and died broke.

Richard Gorges fell hard into alcoholism and in with hard-line nationalists, and began both drinking from morning until night and carrying a revolver around in his pocket. Eventually, detectives tracked him down for “illegal sexual practices.” A scuffle erupted in the house Gorges was renting, and he fatally shot one of the officers in the chest. He served 12 years in prison for manslaughter, and while there, he attempted to use supposed knowledge of the theft to gain release. His information was ignored. Released in 1925, one source says he was struck and killed by a train in London shortly after confessing to the theft in 1944, and that coroners could not identify whether he was killed by accident, suicide, or homicide. Vicious Circle says he lived into the 1950s, but there is not much documentation either way.

Pierce Gun Mahony moved to a family home in County Kerry, where he remained close with Vicars. Vicious Circle claims that the 1908 Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans” was a thinly veiled riff on the theft of the Irish Crown Jewels. In it, a character who may or may not be based on Mahony is murdered in an extraordinary way which at first appears like suicide, related to the theft of priceless government property. In 1914, Mahony was due to have tea with some neighbors. He planned to get there by rowing a boat across a pond. As the pond had many waterfowl, Mahony took a shotgun with him. His body was discovered the next day, near the boathouse. He had been shot through the heart. Foul play has often been suggested, but has neither been proven nor disproven.

Francis Bennett-Goldney was elected to Parliament in 1910, and in 1917 was appointed attache in Paris. In 1918, he was involved in an unspecified motoring accident and died of a renal hemorrhage. A year later, his secret life as a thief was revealed.

Arthur Vicars was disgraced, fired from the job that was his life’s work, and left penniless after he refused a pension that seemed to him like hush money. He relied on money from his brother-in-law and a bit of cash that he got from suing the Daily Mail for libel—the paper admitted that it had invented a story about a Vicars mistress being behind the theft. He insisted on his innocence to his death, and even his will showed that he never got over the incident.

During his later years, at one of his relative’s houses, he continued to act as a unionist, even offering food and shelter to British soldiers who, by the 1920s, patrolled the countryside. Vicars was warned against doing this. In 1921, around 30 armed men broke into his home, pulled him from bed, and shot him several times. A sign was placed around his neck: “Spy. Informers beware. I.R.A. never forgets.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook