The Rise and Fall of Britain’s Biggest Pram Collection

One devoted Englishman accumulated hundreds of historic baby carriages.

Jack Hampshire could never say no to a pram.

Dozens of prams—otherwise known as buggies or baby carriages—hung in rows from custom-built racks on the walls of his barn. In his large 15th-century manor house, complete with a moat, you couldn’t walk without tripping over a Victorian push-chair or an Edwardian baby carriage. He had at least 10 prams in his bedroom alone, his favorite standing at the end of the bed. Antique dolls waved mutely from some of the prams, but most were empty, and all bore the hand-painted number he assigned them on their underside.

“I have always been a keen collector and I hate to see antique objects destroyed,” Hampshire told the Kent & Sussex Courier in 1976. That year, his collection of baby carriages, wheeled bassinets, and coach-built prams surpassed 260. “My collection is a serious attempt to save something from the past,” he said, “and the pram is something no one else seems to want to collect.”

Hampshire, who died in 1996, remains a legend in the “prammie” community. “I would think we would have been lost … without his interest,” says Christine Horne, a pram collector and organizer of the annual “Pramtasia” convention and parade. But in 1976, Hampshire was right: No matter how beautifully made, or how long they’d been in the family, or how important an object of social history they were, no one cared about prams. His mission to save as many prams as he could became a mission to save a history that was fast being lost to landfills and dumps.

Prams were invented in the early 18th century, when British aristocrats who had coaches for themselves decided their children should have some, too. They commissioned beautiful, ridiculous miniature carriages to be pulled by servants, dogs, goats, or small ponies. Victorians transformed what was an affectation of the rich into a necessity. By the turn of the century, prams were cheaper to make, increasingly rolling off assembly lines rather than out of workshops. In post-World War II Britain, more disposable income and the suburban housing boom meant that nearly every family could both afford and needed to have a pram.

When Hampshire started his collection in 1970, the coach-style pram was nearly extinct—parents no longer needed a sturdy pram on a sprung chassis, they needed something that could fold up and be stowed in the back of the car.

Hampshire found his first pram, a Victorian coach-style model bound for the bonfire, at the back of an antique shop in a small town. He’d bought it for his wife, Vicki; they both loved antiques and he thought it would look nice in their home. He repaired its sprung chassis, cleaned it up, repainted it, and was hooked. Hampshire, his son, Nick, said, had always been the clever sort of person who liked to take things apart to see how they worked, who could fix just about anything. After a stint with the Royal Air Force during World War II, “he wasn’t the same person, it did change him a lot,” says Nick. “He was quite a nervous guy and dependent on other people. He was not well for a long time.” Hampshire did odd jobs, building hi-fi systems and doing television repairs for his friends.

“And then he found prams, unfortunately,” says Nick. “It was a bit embarrassing as teenagers, bringing your friends back with lots of prams everywhere. Probably a bit strange for them, fair comment.”

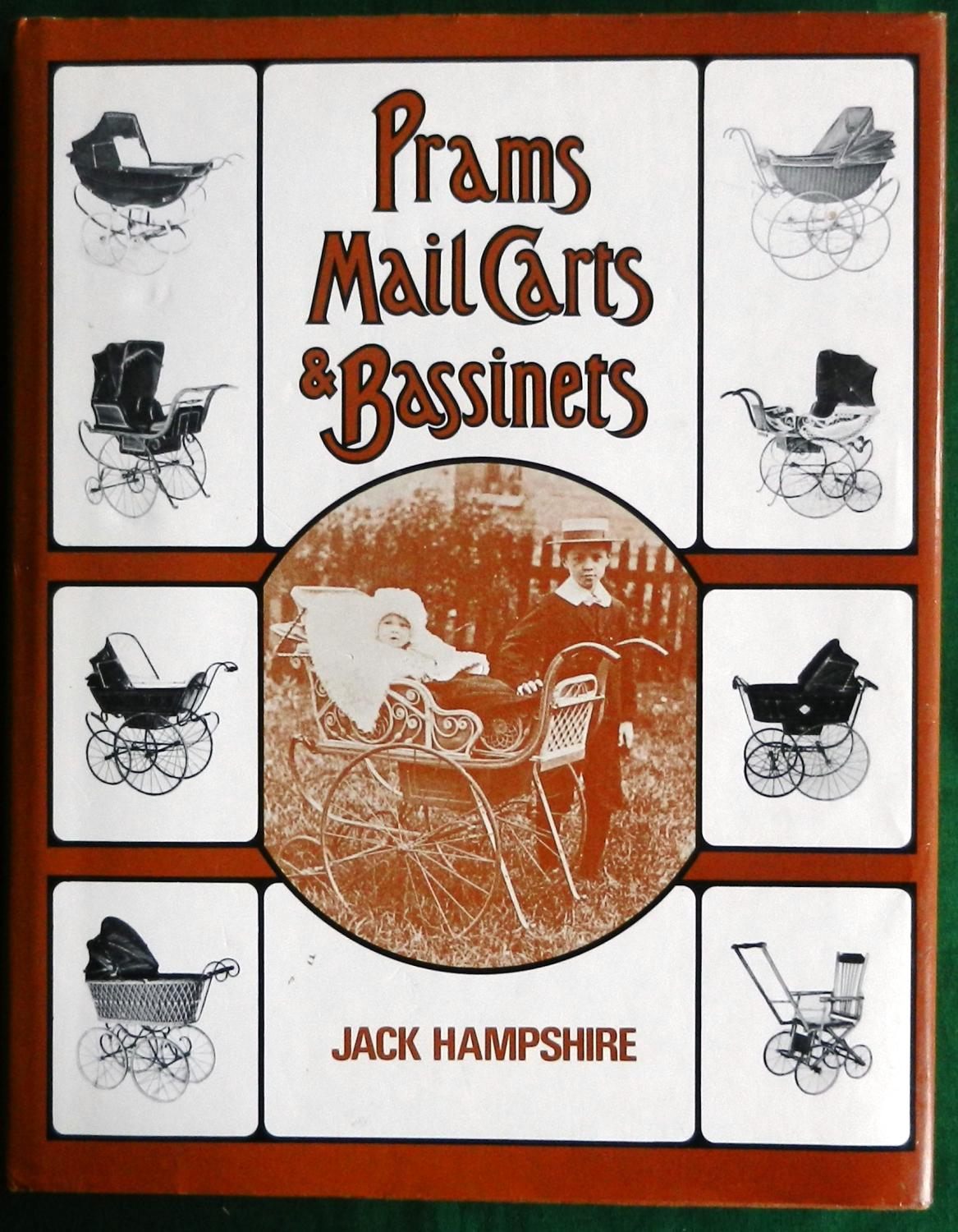

Hampshire became, in an astonishingly short period of time, the world’s leading (and quite possibly only) authority on coach-built prams. He claimed to not know exactly why he loved prams, but they became his obsession. After the death of his wife Vicki in 1976, Hampshire’s collection ballooned to 350. A keen photographer, he’d take pictures of each one and try to compile a history of its use, where it was made, and how. His attraction was largely to their design and how they were made, but he was also frustrated that few people could see the value in preserving an object that had such an impact on the lives of so many. In his 1980 book, Prams, Mailcarts, and Bassinets: A Definitive History of the Child’s Carriage, Hampshire wrote of the pram as a place of discovery: “It is most likely that our very first sight of the open sky with clouds, trees and all the other wonders of the outside world were seen and puzzled over as we lay in our Prams.”

Following Vicki’s death, Hampshire’s eldest son, John, and Nick took over half of the house, declaring it a “pram-free zone.” But the rest of the house was restyled as the Bettenham Manor Baby Carriage Museum, open to the public by appointment. Each year, hundreds of people made that appointment—Nick remembers “coachloads” of people descending on the house to view the prams and to talk to Hampshire.

In 1994, at age 80, Hampshire suffered a stroke that took his voice. By then he’d put the prams, numbering more than 450, into a charitable trust. Hampshire’s hope was that his collection would stay together, telling the story of the British coach-built pram and its intersection with everything from class divisions to women’s rights to international trade. But it was next to impossible to find anyone that could take them all, his three children told The Independent in 1995. Even museums dedicated to childhood didn’t have the desire nor the space necessary to store hundreds of prams.

After Hampshire died in 1996 and his children sold Bettenham Manor, control of the trust and the collection went to a couple from Norfolk, Angela and George Lynne, who collected vintage children’s clothes, toys, and equipment. Nick and his family didn’t keep a single pram, which he regrets.

In 1999, heritage pram-maker Silver Cross took possession of the collection, but passed the prams on after a few years. From Hampshire’s original 460 prams, 68 made it to the Baby Farm, a baby goods retailer in Warwickshire. Its museum was housed in a barn and, like Hampshire’s original museum, operated on an appointment-only basis. But in 2013, the Baby Farm decided to close its showrooms and concentrate on its Internet business; the pram collection again had to move.

“It just got passed around and passed around after his death,” Janet Rawnsley, an amateur pram historian and Hampshire’s neighbor and friend, told me in 2017. “I don’t think anyone could deal with the size of it and the condition of it.”

Rawnsley managed the dismantling of the collection, selling some at auction to private collectors and donating others to the few museums that would take them. But though some museums do have prams as part of their collection, including the Victoria and Albert Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green, none “tell the story” of prams, Rawnsley said. Only Hampshire’s collection, vast and unedited as it was, did.

But though the entire collection didn’t end up in a museum as Hampshire had hoped, the history of prams survived, thriving in the small online groups of dedicated collectors and restorers. “Jack Hampshire” prams, marked by the number he painted on them, go for hundreds on eBay. To collectors, Jack Hampshire is a kind of hero: “It’s an amazing thing to think that this gentleman compiled this history of prams … Jack Hampshire was so amazing and such a character,” says Beccy Meadowcroft, a professional pram restorer. “There isn’t another like him.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook