Every Day at 5:00, Japan Tests Its Disaster Warning System With Folk Tunes

The “5 pm chime” has taken on many meanings over the years.

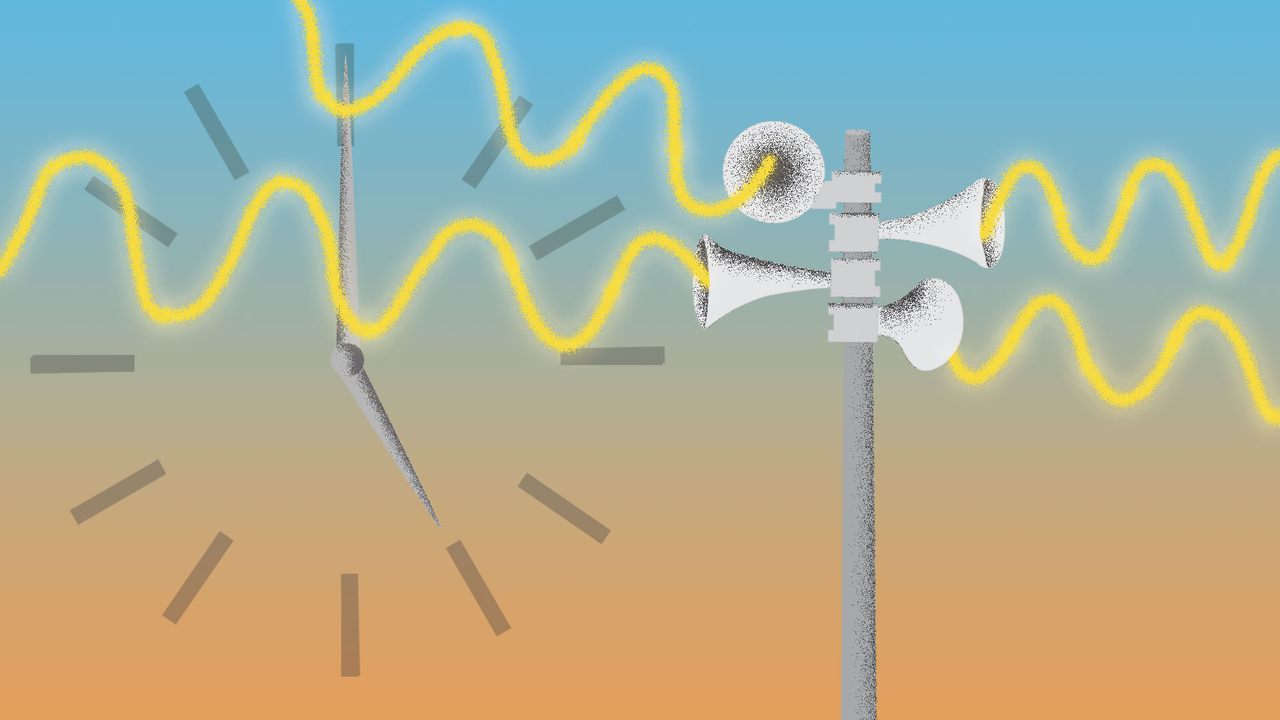

While it is a modern and safe country by most objective measures, Japan nonetheless faces the persistent threat of natural disaster. The nation is entirely located in the seismically active Ring of Fire, making earthquakes an obvious hazard, in addition to the typhoons that have wrought havoc in recent years. As a result, Japan is a country that takes pains to be ready for the worst. Accordingly, dotted throughout most municipalities in the country are banks of loudspeakers mounted on poles, part of a broadcast system that stands ready to alert residents to impending natural disasters or other large-scale civil emergencies.

This network of local warning systems is known as shichouson bousai gyousei musen housou—or bosai musen (“disaster wireless”) for short. Similar to the American Emergency Alert System, the bosai musen network can raise advance warning of earthquakes or provide other vital information in an emergency, allowing residents valuable seconds to find a safe place.

The system is dutifully tested, nationwide, every weekday at 5:00 pm. If you’re imagining a nerve-shredding Klaxon, think again. Rather, the speakers play a collection of Japanese folk tunes or other melodies known informally as the “5 pm chime.” It is part of Japan’s practice of turning otherwise humdrum infrastructure into whimsical works of civic art.

Many municipalities have upgraded to advanced digital systems that allow two-way communication from within homes or designated evacuation points, but the cornerstone of the bosai musen network remains the ubiquitous loudspeakers. Resembling classic air-raid sirens, they’re not much to look at, but Japanese authorities have nonetheless managed to bestow them with a little flash of personality.

For the tests, to avoid unduly jangling nerves, most towns play soothing 30- to 60-second melodies from Japanese folk tunes. A common choice of melody is “Yuyake Koyake,” a folk song popular among schoolchildren. One town, the mountain hamlet of Kanna-machi in Japan’s central Gunma Prefecture, has adopted the “Colonel Bogey March” from The Bridge on the River Kwai as its chime—a curious choice considering the film largely takes place in a Japanese forced labor camp for British POWs. Other municipalities, such as Tokigawa-machi in Saitama Prefecture, play versions of their towns’ peppy, distinctive anthems.

The timing of the tests, which is sometimes adjusted in the warmer months, also serves as punctuation for the day. For some, it signals the end of work. For children, it is an unofficial “go home” announcement. It also reminds drivers to exercise extra caution during and after sunset. Many jurisdictions also append local announcements to the chime. These can include reports on upcoming town events, local news, and reminders for responsible citizenship. In smaller communities, birth and death announcements are also made.

While the tests are designed to be friendly and perhaps a little twee, the network has definitely proven invaluable in emergency situations. In many cell phone videos shot by citizens following the Great Tohoku Earthquake in March 2011, announcements from the disaster wireless system are clearly audible in the background, directing citizens seek higher ground ahead of the approaching tsunami. Piped through the loudspeakers and other devices, warnings from Japan’s sophisticated earthquake warning detection system can provide up to notice before a temblor hits, often the difference between life and death.

The system is not without its flaws and detractors, however. After the 2011 earthquake, there were reports of citizens simply shrugging off the warnings, perhaps out of familiarity or complacency or the belief that the situation was not so serious. The bosai musen system has also been criticized as noise pollution with systems broadcasting at 85dB at a distance of 50 meters (comparable to the noise of a freight train passing by at 15 meters). Indeed, unsuccessful lawsuits have been launched over issues with the volume of the daily tests.

Others take issue with the frequency of the tests, especially since it is not uncommon for municipalities to play the town song and make announcements at 7:00 am and noon, in addition to the usual early evening chime. Still others dislike the length and content of some announcements—it is, after all, largely irrelevant to many and entirely un-mutable.

A search of municipal governments’ FAQ pages reveals the bousai musen system to be a common source of complaints. “There was a tax-payment reminder broadcast recently,” complained one resident of Kadoma City, “Is this the purpose of the system?”

“Can you reduce the number of public relations announcements?” asked another in Yamagata Prefecture.

There are those, however, that take a cue from other fans of Japan’s civic infrastructure, and dutifully catalogue examples of the wide range of bosai musen melodies from across the country.

Detractors and enthusiasts aside, the bosai musen network remains an important piece of the country’s civil infrastructure and an unavoidable facet of Japanese life. Tiring or not, it is another clever way that Japanese insert a little whimsy into the typical architecture of daily routine.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook