The Teetotaling Couple Who Filled Their Home With Novelty Whiskey Containers

For decades, Jim Beam made decanters shaped like Elvis, the Mount St. Helens eruption, and more.

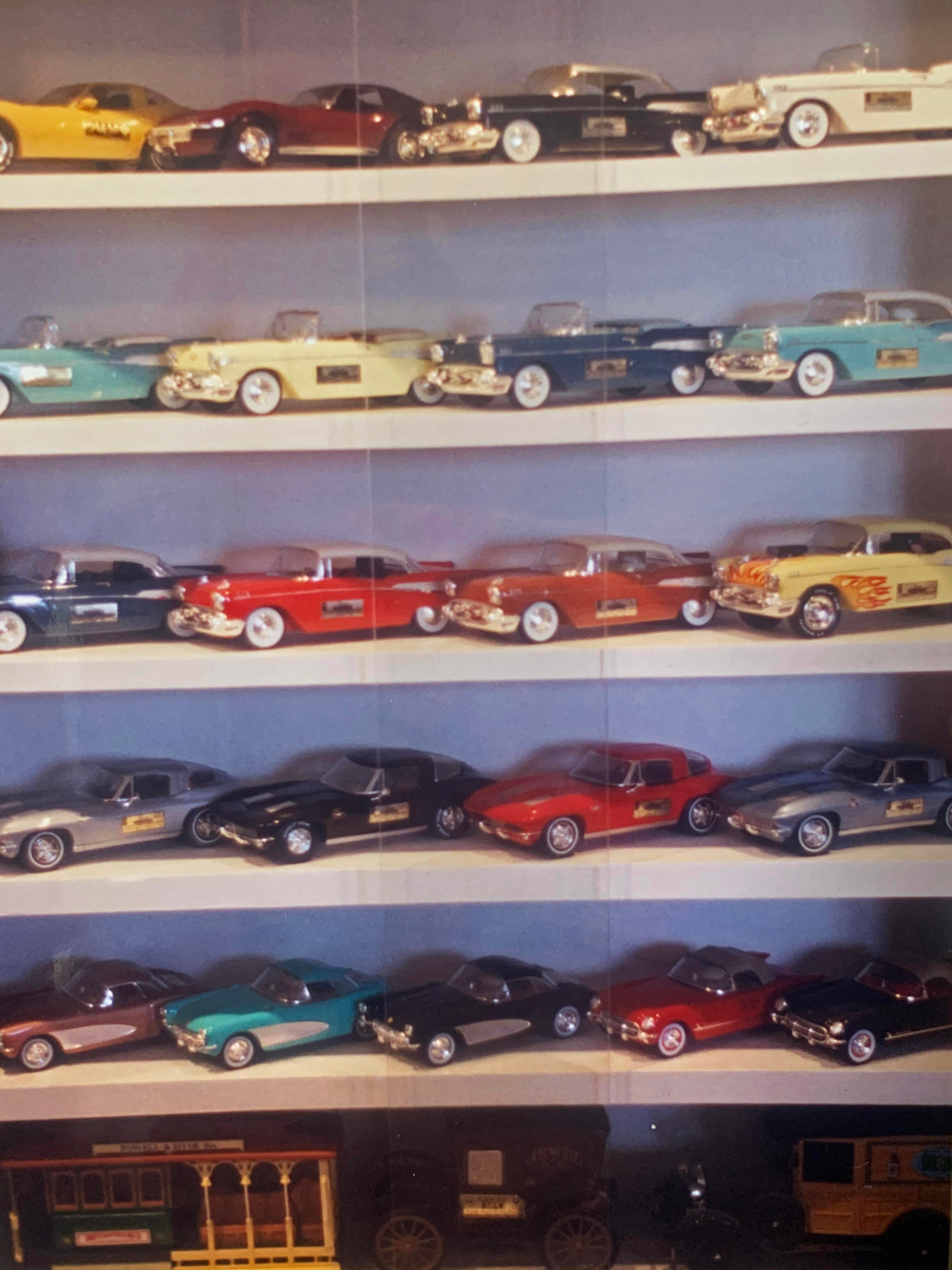

Charles Barrett can rattle off the more than 200 cars in his collection like a waiter might list salad dressings.

“There’s a 1908 black Oldsmobile, a 1909 Thomas Flyer in both blue and ivory, a 1978 blue Corvette, a 1970 Dodge Challenger, a 1957 Thunderbird, a 1964 Mustang, a Jewel Tea truck, a covered wagon,” Barrett says. “If you can think it, I probably have it.”

His armada has never transported a single person, though. Each of the 14-inch-long model vehicles in his fleet are decanters. They’re hollow and, at one point or another, were filled with a fifth of Jim Beam whiskey.

In the 1950s, Jim Beam was looking for a way to sell excess eight- to 10-year-old liquor. Vodka companies were staking a claim on the American South, and whiskey sales were plummeting. So Jim Beam needed a gimmick to get people to buy the alcohol they were aging in expectation of big paydays.

Enter campy ornamental decanters. Unlike the sleek, understated crystal decanters widely sold today, these decanters were often ceramic statuettes, meant to be collected and displayed.

It wasn’t just classic automobiles. Between 1955 and 1992, Jim Beam collaborated with the Illinois-based ceramics company Regal China to produce thousands of decanters. While other bourbon and whiskey companies, including Jack Daniels and Sazerac Company, the makers of Old Rip Van Winkle, manufactured their own versions, none came close to the breadth of Jim Beam or the zeal of its impassioned collectors.

Barrett can tell you all about the Jim Beam decanters. Because he has just about all of them. He has decanters that look like Elvis and Hank Williams (both senior and junior), Paul Bunyan and Santa Claus. His shelves are crowded with woodland critters and circus animals and decanters that evoke decades of current events, from an early personal computer to the Mount St. Helens eruption, complete with a vial of ash from the 1980 explosion. Oodles of them are niche models made for conventions or causes. He even has eight-foot-long train sets, where each piece is its own decanter. Barrett keeps his collection meticulously organized in his Tennessee home, grouped by theme and arranged, an inch apart, by size and color. A dedicated dusting schedule keeps each piece show-ready.

In 1980, Barrett and his late wife, Betty, came across Jim Beam decanters for the first time. “We didn’t know anything about them, we just liked them,” Barrett says.

Their first eight depicted states. They scooped those up with the intention of collecting all 50, but the company never got around to making every state.

“One thing led to another, and once you get 10, you want 20, and once you get 20, you want 50,” Barrett says. “We just kept collecting.”

Their first real indoctrination into the Jim Beam collectors’ world was at a flea market in Nashville. Amidst 3,000 vendors, Barrett spent most of his time talking to another couple that had twin tables of decanters for sale. The proprietor told Barrett there was a bottle show happening in the basement for the Jim Beam Bottle and Specialty Club. There, the Barretts found their people.

Beth Hellwig, the current president of the International Association of the Jim Beam Bottle and Specialties Club Collectors, says during their organization’s heyday there were more than 7,500 paying members and likely thousands more casual collectors. Zealots had their prefered decanter dealers, and rivalries could be fierce, since the Jim Beam company stoked the consumerist fire by frequently releasing rare items. Now the roughly 500 remaining members, most of them octogenarians, have mellowed with age, like a nice whiskey.

Barrett has always done his tchotchke hunting on the road. Each Saturday for a decade, he and Betty got up early and drove towards Knoxville, Nashville, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Birmingham, or Chattanooga, hopping between flea markets and antique stores. While many of their finds are valued between $5 and $50, their four rarest decanters are worth a combined $68,000, at least in the eyes of collectors like Barrett. Now 84, Barrett says he’s never wanted the Internet or a mobile phone, not even for collecting. Much of the appeal was the time spent with his wife.

Though the Barretts didn’t attend international conventions in recent years due to Betty’s heart issues, they are well known because of the magnitude of their collection. Barrett says he’s sure he has the biggest in the country. In fact, they built an addition onto their home just to display it all.

“Betty told me when we started, ‘I don’t care how many you buy, but you’re not going to stack them up on the floor or put them in boxes,’” Barrett says. “She said, ‘If you’re going to have them, you’re going to display them.’”

Their 900-square-foot addition is filled with 52 custom-made, all-glass cabinets. Each one is 34 inches long, 76 inches tall, and full of Jim Beam decanters. He says he has more than 1,650 decanters and 1,000 more auxiliary Jim Beam trophies, such as decorative plates and statuettes.

Although the decanters could hold more than 330 gallons of whiskey (roughly the holding capacity of a hot tub), Barrett lives in a dry county, and he doesn’t drink. For him and Betty, it was purely about collecting. Of all those in his vast collection, Barrett says his favorite decanter is always “the next one I don’t have.” According to Barrett, he’s only missing two Jim Beam decanters, which he hopes to get this summer on his way to the 50th National Convention of the Jim Beam Collectors. His new favorite, he’s sure, will be a model of the shuttle used for tours at the Jim Beam distillery.

Betty’s favorite was a space shuttle, modeled after NASA’s The Enterprise. Her least favorite was one of King Kong. “I could never figure out if she didn’t like it because it was ugly or because a pretty flight attendant gave it to me,” Barrett jokes.

Barrett doesn’t do as much hunting anymore—it’s not as fun without Betty riding shotgun—but he still enjoys it on occasion, even though he rarely finds something he doesn’t already have. Barrett is also trying to find a home for his collection, which he doesn’t want sold off in pieces after he’s gone. He’d rather donate it all so others can enjoy this piece of Americana history.

“I’m real proud of our collection,” Barrett says. “For a long time, this was a way of life. And it was wonderful.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook