How Two Oz-Obsessed Midwesterners Made Judy Garland’s Birthplace a Museum

“This is as important to me as any President’s house.”

On a cold and snowy March day in 1938, Judy Garland took a train from Chicago to Minneapolis and set off on the three-hour drive to her birthplace: Grand Rapids, Minnesota. She was 16. The following year, The Wizard of Oz would make her famous as the girl with the red slippers, but she was already well-known as a child actress and singer. John Kelsch, the co-founder of the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, says that a crowd marveled as she stepped out of the car in a leopard-skin coat and hat. Some apparently asked, “Who is that?”

“It’s a swell state, Minnesota,” Garland said after her trip. “I’m proud it’s my home, and I know a few hundred thousand of us who feel the same way.”

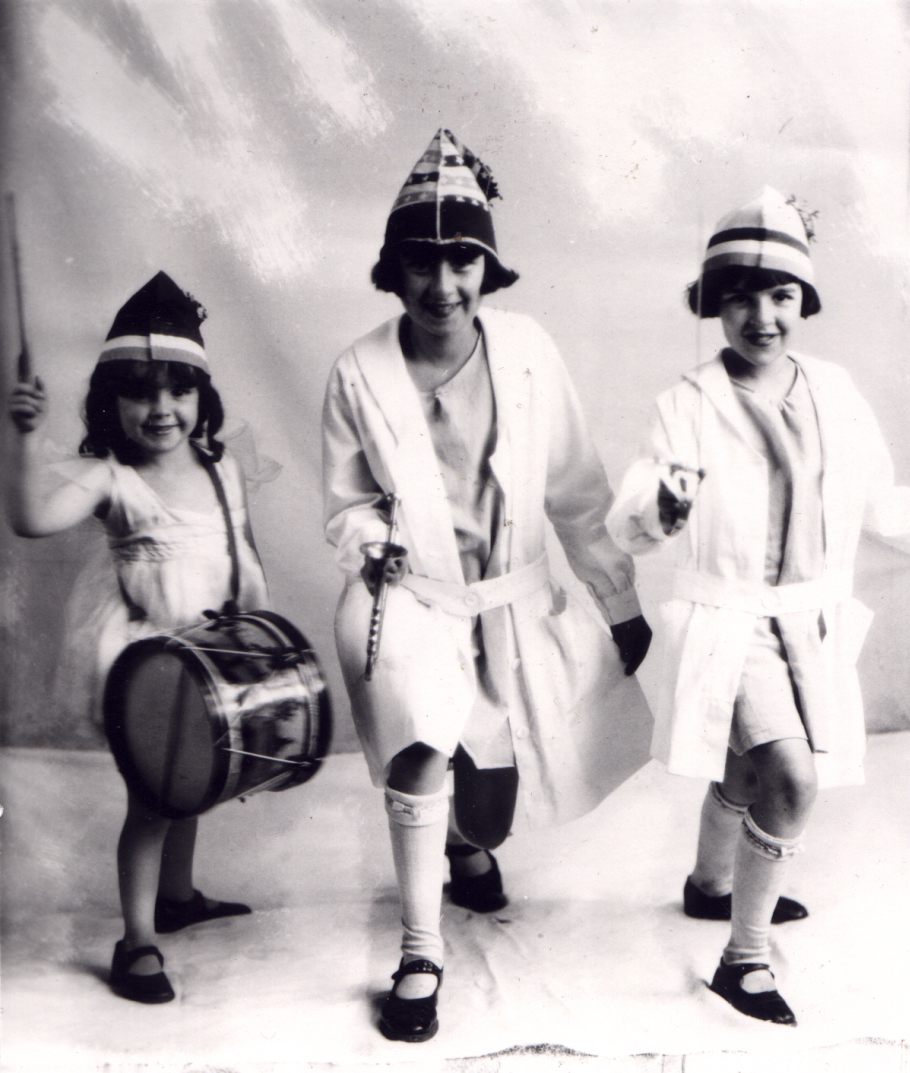

Today, a glass case in the museum houses the very hat and scarf that Garland wore on that cold evening when she climbed out of the car. It’s displayed alongside an Andy Warhol screen print of Garland, props from The Wizard of Oz, dolls, and original photos of Garland and her three sisters. They’re collected in the wood-frame house where Garland was born in 1922, a structure that was built by a steam boat captain way back in the 1890s.

“In terms of American history, and the fact that The Wizard of Oz is one of the most watched movies of all time, this is as important to me as any President’s house,” Kelsch says, walking around the enchanted garden on the south side of the building. Passing cutouts of munchkins, and others of Dorothy and her companions strolling down the yellow brick road, Kelsch goes further: “Does anyone know who Grover Cleveland is? Would they want to visit his house?” (Not particularly, he says.) Garland’s childhood home remains an attraction, in part because so many children knew her as Dorothy. The wooden house even looks like the one that landed on the Wicked Witch of the East more than 80 years ago.

Judy Garland was born Frances Ethel Gumm in 1922. Her parents were vaudevillians who ran a theater, which provided an escape for the working-class population of this northern Minnesota town. Once, when she was very young, she sang at her father’s theater, Kelsch says. The song was “Jingle Bells,” and she sang it over and over, each time receiving a raucous applause. Her dad eventually had to come and cart her off the stage, according to Kelsch. In her later years, studio executives liked to play up Judy’s small town upbringing as a way to enhance her image as the wholesome girl next door—an image that helped her land the role of Dorothy.

Kelsch has devoted half of his life to preserving Garland’s legacy in the town. In 1986, he graduated from New York University with a masters degree in museum studies, but he says he had no interest in the politics of a big museum. “I want to get things done,” he says, dressed in red flannel, jeans, and sneakers. Kelsch looks more like a carpenter than a museum’s executive director. Almost as if he doesn’t want to overshadow Judy’s legacy.

In 1989, Kelsch was working for the Itasca County Historical Society, maintaining a collection that included the history of the town’s logging industry. He says that the society had a few dusty scrapbooks that chronicled Garland’s four years in the town, but nothing substantial. (A precursor of the Judy Garland Museum, founded by Jackie Dingmann, had been set up in a former high school built from local stone.)

That’s when Kelsch was introduced to Jon Miner, a former Minnesota printing magnate who was interested in preserving Garland’s legacy. In 1991, Miner purchased Garland’s childhood home. He also bought the carriage that Dorothy and her companions rode through the Emerald City, along with one of the dresses she wore in the movie. “I paid $13,000 for a dress,” Miner says with a laugh. He claims that it’s now worth millions.

Shortly after he purchased the house, Miner entrusted Kelsch with the day-to-day operations of the museum. They’ve been partners ever since, and Miner says he’s invested millions in Garland’s legacy. He’s even been after the city council to change the slogan of the town from “It’s in Minnesota’s Nature” to “There’s no place like home,” he says, complete with an image of the ruby slippers. “Brainerd has Paul Bunyan,” Miner says. “We have Judy Garland.”

The road leading to Grand Rapids is no yellow brick road, but it is beautiful. Not in a 1940’s technicolor kind of way, but the kind of slow beauty reserved for those who endure the brutality of the state’s winters: sweeping views of lakes, fields of red and gold leaves. The two-lane road from Minneapolis hugs Lake Mille Lacs, which is known for wild rice and walleye. Winds whip the waters of the lake, tossing small boats about. Small bait shops are still doing a brisk business, and diners offer home cooked-food and charm.

It looked and felt quite different in Garland’s day. In the 1920s, Grand Rapids was still a rough and tumble logging town with lots of Finns, Swedes, Norwegians, and Germans. Many were farmers and lumberjacks well versed in hard, blue-collar work. During that time, Christmas was a tradition brought from back home, and many people spoke the languages their grandparents had spoken.

Judy Garland’s house used to be located near the town center, not far from the antique shops, variety stores, and Old Central School building that occupy the area today. But the house has moved three times over the years, and today it sits with an adjacent children’s museum on Pokegama Avenue, near some strip malls, a small hotel, and the occasional farmers market.

“Grand Rapids is no Emerald City, to be sure,” says Bill Convery, of the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul. “But Judy Garland visited Emerald City, and I think Grand Rapids is proud that they have someone who kind of touched that dream. And I think they have every reason to be proud of that.” He points out that for locals, Judy Garland is not only a historical figure, but also a symbol. “In many ways the Judy Garland Museum is about history, but it’s also about our hopes and our dreams.”

At the same time, Convery isn’t sure how institutions like the museum will sustain themselves over time. “I wonder how people are going to remember Judy Garland,” he says. “We’re getting to a time in our history where I think more and more people who went to Judy Garland movies as kids are passing away.” Future generations will have to discover her by looking back—several books about Garland have come out in recent years, and a biographical film called Judy, starring Renée Zellweger, comes out this month.

Not all the memories of Judy Garland are as shiny as the ruby slippers she wore in The Wizard of Oz. (The museum had one of the original pairs on loan, until the shoes were stolen in 2005; the museum replaced them with replicas that fans sent in, and the originals were recovered in 2018.) At the entrance to the museum, there’s a long description detailing Garland’s struggles with addiction, her relationship issues, and the challenges she experienced in her career.

Kelsch felt it was important for the museum to address those complexities at the very beginning. “We didn’t want to hide anything,” he said. The story of Garland’s untimely death, to an accidental overdose in London at the age of 47, still casts a shadow over many stories of her life. End of the Rainbow, a 2008 play that has been staged on Broadway and on West End in London, is set during the difficult months before her death.

But Kelsch and his fellow fans don’t remember her that way. He still remembers when he heard one of Garland’s recordings, on a cassette tape in his hometown of Bismarck, North Dakota. “I just couldn’t believe anyone could sing like that,” he says. He remembers that his mother asked him, “Are you sure you want to spend your life in a small town?” His answer was yes.

Maintaining the museum, for him, is a labor of love. “I do everything,” he said. “I raise the money. I help build the exhibits and I keep the lights on.” Garland seemed to remember Grand Rapids as the place she lived before her life began to be corrupted by show business. Her time under contract at MGM Studios was often brutal. The hours were long, and studio executives ragged on her for not being pretty enough, not being thin enough. In a way, life in Grand Rapids must have represented a place she could hold on to, the place where she first began to dream of the success she ultimately achieved.

“Basically, I am still Judy Garland,” she wrote to a fan in 1958. “A plain American girl from Grand Rapids, Minnesota, who’s had a lot of good breaks, a few tough breaks, and who loves you with all her heart for your kindness in understanding that I am nothing more, nothing less.”

There is history as it was, and history as we wish it could be. The Judy Garland Museum contains a bit of both. Judy Garland was an actress, a singer, a star—and, like the Wizard of Oz, she was a maker of myths. Garland’s evening gowns, her makeup kit, the gifts given to her by other stars like Frank Sinatra—all these items invite visitors to participate in that same myth-making. In her childhood home, even Grand Rapids can start to feel like the poppy fields of Oz.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook