This British Colonial Report Offers a Rare Glimpse Into India’s Historic Cannabis Cuisine

And a description of some very stoned canines.

Thick, sugary, and creamy, rich with saffron and almonds, bhang thandai is so sweet that at first it’s hard to pinpoint the drink’s secret ingredient. After a sip or two, however, the telltale taste lingers: spicy and slightly musky, it’s the signature whiff of cannabis. After a few minutes, the high comes, dreamy as the rainbow play of Holi colors. An Indian festival staple, drunk especially during North Indian Holi celebrations, bhang thandai is part of a long history of South Asian cannabis culture.

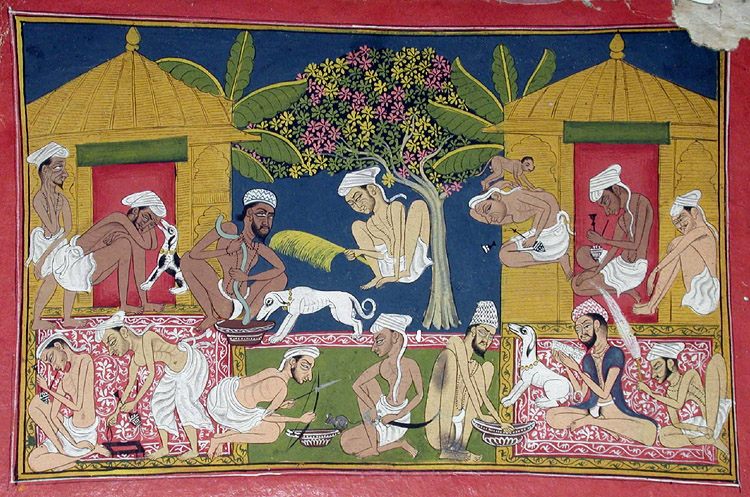

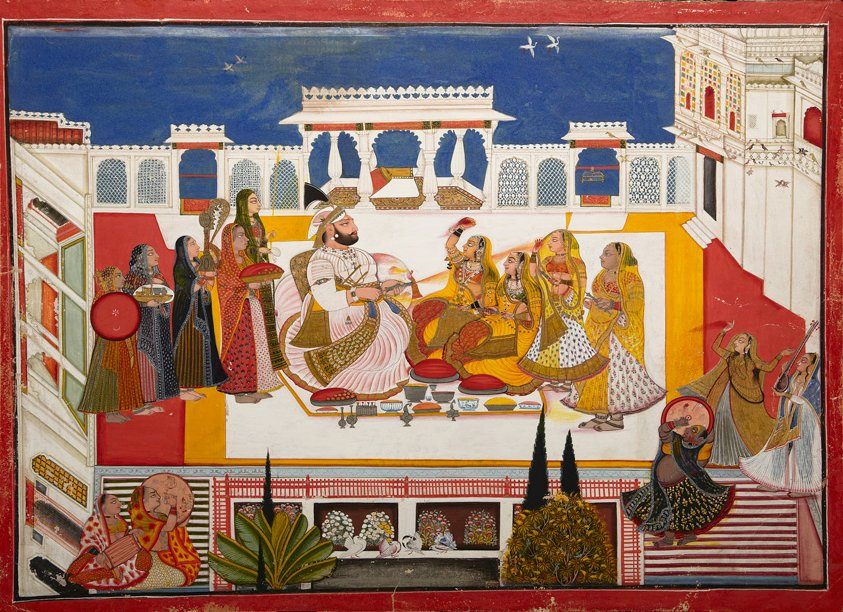

Mentions of cannabis in South Asia date back to at least around 1500 BC, where it makes an appearance as one of five sacred plants in the Atbarva Veda. Beloved by Sikh soldiers and Mughal kings, cannabis has also long been part of spiritual practice across South Asian religions, from Shiva devotees who smoke the god’s treasured herb, to Sufi seekers who use hashish as a tool to unite with the divine. Today, bhang recipes are widely available, and the drink, made from the leaves of the plant, is legal and broadly accepted. Yet British colonialism dramatically shaped modern attitudes toward cannabis in South Asia and, in turn, around the world.

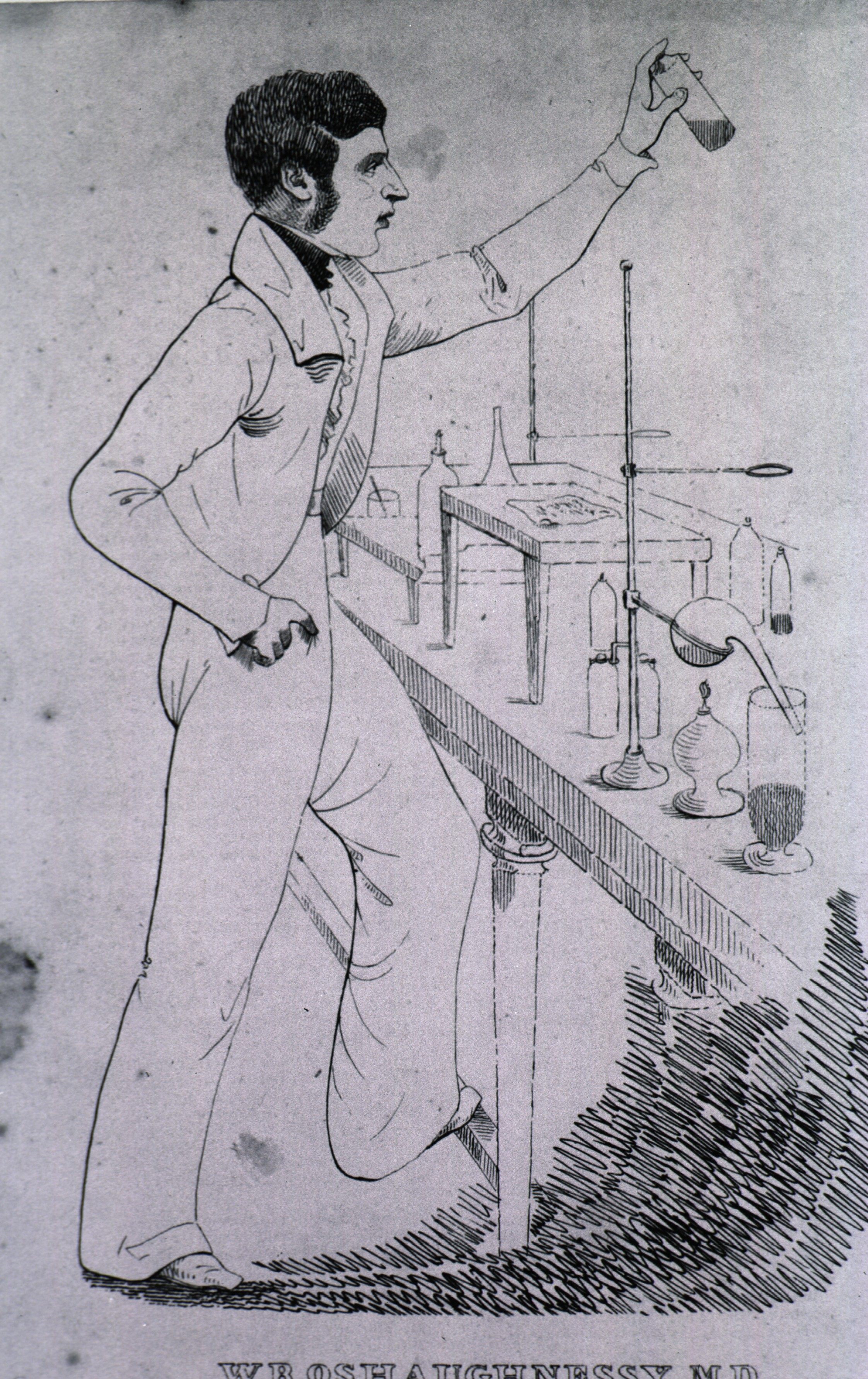

William Brooke O’Shaughnessy could have given you a bhang recipe or two. In early 1830s England, O’Shaughnessy, a young Edinburgh graduate, had gained recognition as a clever chemist. But when he found himself unable to acquire his license in London, he followed in the footsteps of many a young British lad unsure of his next step, and hightailed it to the colonies.

At that time, India was still controlled by the East India Company; it wouldn’t be officially “transferred” to the British crown until 1858. But in the colonial capital of Calcutta, British elites, often in collaboration with elite classes of Indians, had embarked on a grand scholarly mission. Their aim was to learn everything possible about the subcontinent, from its history and languages to its flora and fauna, in order to better understand—and thus, better control—the Indian population. O’Shaughnessy, the bright, young Irish physician, was no different. Upon his arrival in Calcutta, he took up a post at the Medical College Hospital, where he turned his attention to studying a unique aspect of Indian medical and culinary culture: cannabis.

At the time, cannabis use was uncommon in England, and British colonials regarded the drug with suspicion. They had long feared that cannabis could cause madness, and 19th-century colonizers considered its use a threat to colonial power. “Murderous assaults by individuals under the influence of Indian hemp have been somewhat frequent,” declared one Bombay newspaper in 1885. As a result of this violent influence, an Allahabad newspaper opined, “The lunatic asylums of India are filled with Ganja smokers.” This was true, but not necessarily because the drug caused madness. Instead, officials running “native-only” colonial asylums sometimes admitted Indian people suspected of being habitual ganja smokers for the mere fact that the system regarded them as unruly.

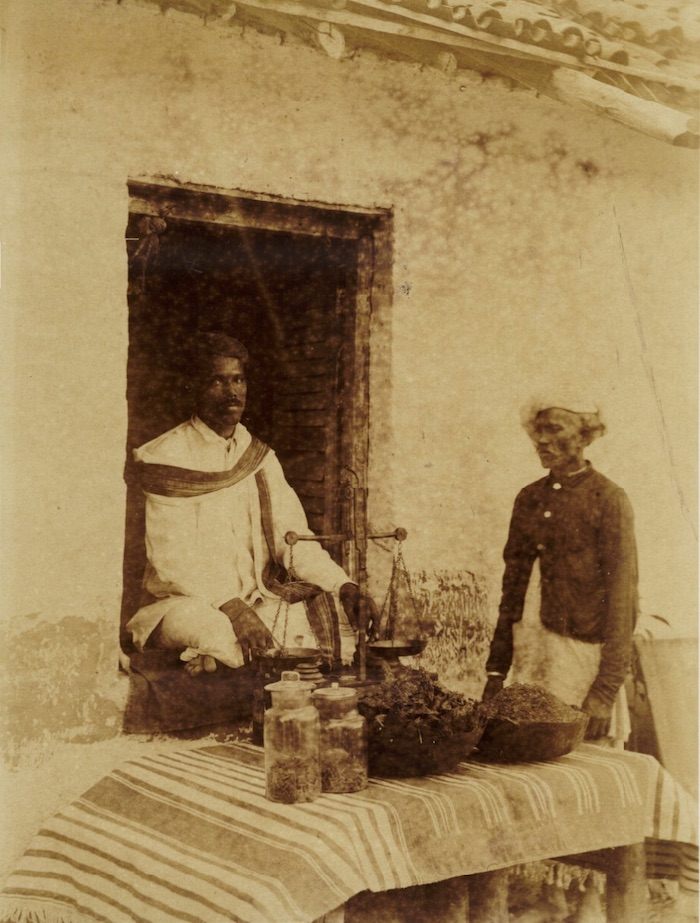

But British colonials were interested in anything that could yield knowledge about the colonized population. So in the 1830s, O’Shaughnessy set out on a rigorous program of research, detailing his inquiries in his 1842 The Bengal Dispensatory. Drawing from interviews with Indian colleagues, The Bengal Dispensatory provided—among descriptions of hemp plants and hemp-related literature in Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian—several cannabis recipes detailed enough for an ambitious home chef to attempt today.

To make sidhee, subjee, or bhang—drinkable cannabis preparations similar to bhang thandai—O’Shaughnessy writes: “About three tola weight [of hemp seeds] are well washed with cold water, then rubbed to powder, mixed with black pepper, cucumber, and melon seeds, sugar, half a pint of milk, and an equal quantity of water. This is considered sufficient to intoxicate an habituated person. Half the quantity is enough for a novice.”

He provides similarly detailed descriptions of majoon, or ma’jun, a cannabis-infused milk-based sweet that was a favorite intoxicant of the Mughal emperor Humayun. After providing a recipe for weed ghee that would make any contemporary brownie-baker proud, O’Shaughnessy details, “The operator then takes two pounds of sugar … when the sugar dissolves and froths, two ounces of milk are added; a thick scum rises and is removed.” Finally, the chef adds the cannabis butter, pours and cools the mixture on a pan, cuts it into small slabs, and enjoys. While O’Shaughnessy labels the consumption of these delicacies a “vice,” he also notes that the effect of bhang intoxication is “of the most cheerful kind, causing the person to sing and dance, to eat food with great relish, and to seek aphrodisiac enjoyments.”

O’Shaughnessy would know. Aside from collecting cannabis recipes, he decided to run experiments to understand the effects of the drug first-hand. From his post in the Medical College Hospital, O’Shaughnessy recruited patients (sometimes with dubious ethical standards: his subjects included children and some very stoned dogs) to be part of what Sujaan Mukherjee, a research scholar at Kolkata’s Jadavpur University, argues were the first clinical marijuana experiments of modern Western medicine. In articles published between 1839 and 1843, he details the results of his investigations into the potential of cannabis to treat seizures, rheumatism, and cholera.

His study notes are high comedy. Half an hour after giving a dose of Nepalese hash, dissolved in spirits, to a “middling sized dog,” O’Shaughnessy records, the dog “became stupid and sleepy, dozing at intervals, starting up, wagging his tail as if extremely contented, he ate some food greedily.” Besides puppies with the munchies, O’Shaughnessy gave his tincture to several human subjects, one of whom “became talkative and musical, told several stories, and sang songs to a circle of highly delighted auditors.” Intriguingly, O’Shaughnessy found that hemp was effective in treating “infantile convulsions”—over 170 years before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration came to a similar conclusion.

By the 1894 publication of the British government’s Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, the notion that cannabis caused murderous madness had been partly put to rest. Analyzing the results of a survey of over 1,000 British and Indian sources across the subcontinent, the Report concluded that while “it may be accepted as reasonably proved in the absence of other cause that hemp drugs do cause insanity,” cannabis consumption could be acceptable in moderation. “As a rule,” the report concluded, “these drugs do not tend to crime and violence.” In the final decades of their reign, the British government, considering cannabis use too culturally significant to ban and too difficult to regulate, put their attempts to outlaw the drug to rest.

Yet the legacy of Western ambivalence toward marijuana would come back to haunt South Asian countries even after they gained independence. Western skepticism toward cannabis, which countries like the United States and Britain associated with populations of color, persisted after decolonization. In 1961, the World Health Organization commissioned the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, part of the worldwide push toward narcotics prohibition. Classifying cannabis in the most dangerous and restricted category, the Convention perpetuated Western beliefs about the dangers of marijuana—in contrast to protest from South Asian signatories, who reserved the right to regulate cannabis on their own terms. Today, Indian law reflects a kind of compromise, influenced by both global drug policy and the historical belief of some elite Indians that edibles are more socially acceptable than smoking. Consuming the leaves of the marijuana plant, used to make bhang, is legal throughout much of India, but smoking the resin and buds is mostly forbidden.

This ambiguous legal status hasn’t stopped the popularity of South Asian cannabis culture. From the smoky ablutions of wandering Shaivite sadhus to everyday ganja smoking on the street, from tall glasses of bhang lassi to rose-scented thandai, cannabis continues to enjoy an exalted position in many South Asian communities. With marijuana legalization leading to a rise in cannabis cuisine across the United States, it seems that—almost 200 years after William O’Shaughnessy compiled his rudimentary cannabis cookbook—the West may have finally caught up.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook