Medellín’s Bright Future Is Tangled Up With Its Dark Past

Decades after the end of the narco era, a Colombian city wonders if it is better to forget.

In the mountains above the sleepy Colombian suburb of Envigado, there’s a startling, quetzal’s-eye view of the city of Medellín, nestled in a bowl-shaped valley, studded with red and white skyscrapers, and laced with public gondolas that climb into hills to serve neighborhoods once thought too dangerous to visit. A few years ago, monks from a Benedictine order acquired this lofty site—called “La Catedral” (The Cathedral)—and transformed it into a monastery and senior citizens’ home. There’s a spare hilltop chapel, statues of saints, and quaint red-tiled living cottages. La Catedral feels today like a meditation retreat, halfway to the clouds.

A blank wall beneath a concrete overhang prompts my Colombian guide, David Rendon, to pull out his phone. “Look,” he says. He shows me a picture he took just months ago of the same wall—covered with a blown-up photo mural of drug lord and native son Pablo Escobar and the message, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Cautionary and repentant though the message seemed, the monks have since removed it. “They don’t want to be related to it anymore,” Rendon says. A few feet away from the newly blank wall, there’s another banner that proclaims, “Atone for our sins, and we will save our souls.”

If there is a sin that the city of Medellín still feels the need to atone for, it is named Escobar. Half a lifetime ago, La Catedral was his notorious pleasure-palace-cum-prison. In 1991, he presented himself here for a negotiated prison term that was supposed to last five years. But it was incarceration on his terms, and the South American jungle is only just starting to reclaim the final remains of the excesses of what was called “Hotel Escobar.” There’s a frayed soccer net, a wooden stable that once housed prize horses, and a plaque that reads, “Ruins of one of the pleasure rooms, with its round and rotating bed.”

La Catedral’s evolution reflects Colombia’s uneasy relationship with its past and its doubts about the future. Understandably, many Colombians resent the way Escobar and his fellow criminals have come to define their national identity. Some are eager to move on, to transform, to escape a gawking, bloody tourism in favor of something more enduring or inspiring. “Our presence here means that we are committed to cleanse the face of Envigado, to apologize for that turbulent past, not only here but throughout the city and the country,” a priest from the monastery, Gilberto Jaramillo Mejía, told Colombian daily El Tiempo when it was established.

But plenty of people are comfortable in Escobar’s shadow; he was beloved by some and his legacy remains a source of vicarious thrills and very real profit. Foreigners, high on the narco mythos, take selfies at his grave. Locals, especially those born after his 1993 death in a shootout, aren’t immune, either. Teens still ask a former cartel assassin, Jhon Jairo Velásquez Vásquez, for his autograph in the street. And the cocaine trade persists, though more fragmented, more tolerated, more quietly. Cocaine production has been rising steadily since 2012, which is one factor that pushed voters to president Iván Duque, who ran on a law-and-order platform.

It’s impossible to tell exactly what the future of Medellín will look like, but today there seem to be two cities, superimposed atop one another: one still infatuated with the thrill of transgression, and another attempting to face down its own worst impulses.

There is a well-trod route for the narco-obsessed visitor. It includes the Monaco Building, where Escobar and his family occupied the penthouse, the rooftop where he was gunned down after “escaping” La Catedral, and the streets of Envigado itself, where he grew up. Some enthusiasts even pay a visit (and an entry fee) to Pablo’s brother and narco-accountant, Roberto, who maintains a cartel-era museum in his house. T-shirts featuring Pablo’s famous mugshot—charming smirk and all—go for about $10.

This is, in an academic sense, called “dark tourism.” It involves fascination with criminality or violence, and also the catharsis gleaned from once-dangerous places where peace again reigns. Americans in particular, according to Anne-Marie Van Broeck, a dark tourism scholar at Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, have a long-standing obsession with outlaw individualists. Escobar fits that profile, alongside Ma Barker and Al Capone.

For Colombia, responding to a new swell of international interest in Escobar means finding some kind of balance, which other nations have negotiated with varying degrees of success. In Poland, the national mood about maintaining memorials to victims of the Nazis is conflicted. Some death camp sites, such as Auschwitz, have been well-kept, while others, such as Chelmno, have been all but forgotten. And in Cambodia, the development of a memorial attraction at the Choeung Ek Killing Fields has upset many. Reportedly, some guides have even dug up bone fragments to give to visitors. (Escobar’s crimes are on a different scale than these, but his cartel’s body count is in the thousands. Cartel wars resulted in the murder of a staggering 4,367 Medellín residents in 1990 alone.)

In Medellín, many, perhaps most, people are disgusted by the renewed focus on El Patron, as he was known. It’s hard to find a person who survived the era who doesn’t have some sort of connection to one of its victims. The wounds are fresh enough, Rendon says, that lots of people give him a hard time for showing visitors anything to do with Escobar. “The other day, a guy said to me, ‘I can’t believe you’re showing them this part of the city.’”

Other residents turn to an irritated silence. Near the rooftop where Escobar was killed by Colombian soldiers, an old woman sits in her front yard breathing from an oxygen tank. Rendon tells me she lived here during the height of the drug wars.

“Does she remember anything?” I ask.

“Of course she does. She doesn’t like to answer questions,” Rendon says. “A lot of times people just hide, or they close the doors.” A few moments later, I notice the woman has gone inside.

For Diego Buitrago Pérez, a 20-something local who works at a hostel in Medellín’s El Poblado neighborhood, total silence feels over the top. He happily talks about how the cartel wars shaped present-day Colombia, but also he’s happy to move on. “I don’t like to stand in the past,” he says. “It’s a new country now.” He sees people looking to make a quick buck off of tourists’ sinful fantasies, which is not the Colombia he wants people to see. “It’s okay if you want a piece of that story. But not too much.”

In the mid-’80s, when Rendon was about nine years old, his family moved to suburban Long Island to escape the violence. But every six months, he and his parents returned to Medellín for visits, and the contrast was jarring. “I would come back here, and I wouldn’t even be able to go in the streets after six.” These days, when fellow Medellín residents call him out for teaching visitors about the cartels, he pushes back. “This is part of our history,” he says, “and we should share it.”

Tourism expert Van Broeck agrees with Rendon, saying that fascination with the malign can eventually lead tourists to fuller, more nuanced perspective of a destination. “You’ve never had a better promotion for Colombia,” she says. “Say, ‘Look at our past, and look at how beautiful it is now.’”

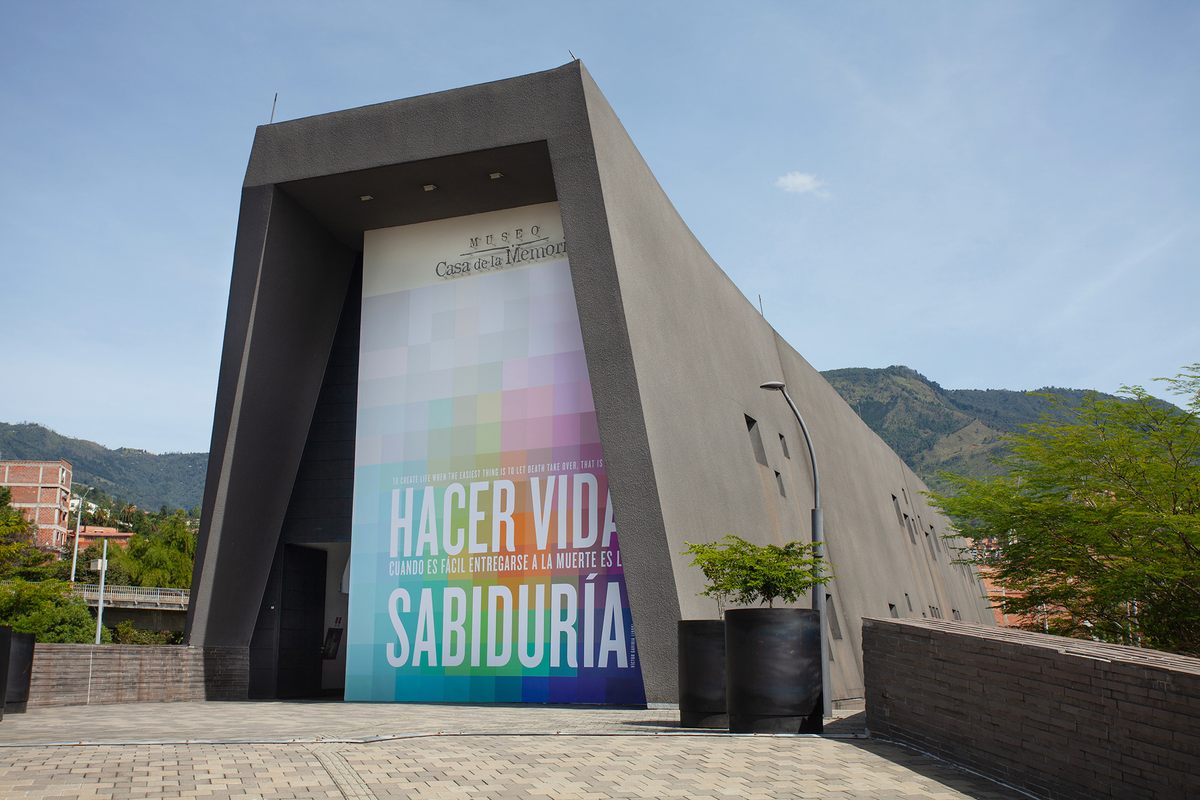

Perhaps the next stage in this process, after indulgence, is reckoning. The most obvious site for this in Medellín is the Memory House Museum (Museo Casa de la Memoria), tucked into an unassuming residential neighborhood.

Opened in 2013, the museum spotlights the victims of violence in Medellín, rather than its perpetrators. Inside, stark angles destabilize viewers, and dark panoramas are pierced by narrow beams of light. In the largest exhibit room, screens play video testimonies from people who lived through the country’s bloodiest escapades, and in another, photographs of victims light up one by one, then disappear, evoking a starry night sky.

The Memory House isn’t packed the day I visit, but it hosts a steady stream of visitors. “We have to be aware of what happened to families,” says teenager Brenda Zapata of Medellín, who is sitting outside with some friends. She sees the reality of the violence as important, in part, because some of her peers still equate Escobar-style vice with glamour and success. “There are many young people who want to be involved in crime,” she says.

While the murder rate has dropped by more than 90 percent since the narco years, Rendon agrees that there are still plenty of reasons to keep the history alive as a cautionary tale—to get people, and especially the city’s youth, to confront the reality and risk of corruption today. “We’re exporting more cocaine now than when Pablo was around,” he says. The difference is that politicians are more involved, he asserts, and rotate out of office every few years so no single criminal figure emerges. But despite his concerns about the ongoing rot, Rendon is optimistic.

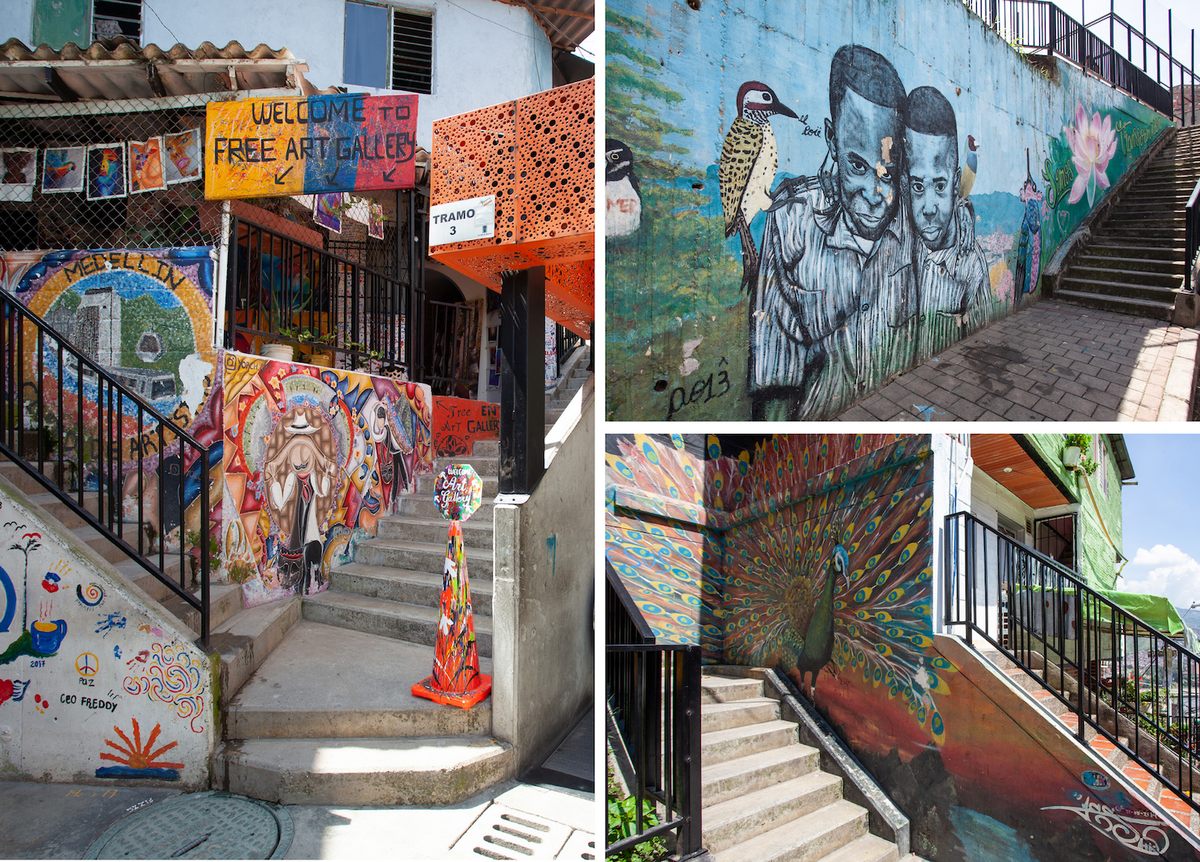

That turn is evident in the Comuna 13 neighborhood, once a place where Escobar chose and groomed his loyal assassins, known as sicarios. Thirty years ago, “it was so common to see bullets flying around the neighborhood,” Rendon says. “People took out white sheets to demand peace.”

These days Comuna 13 has evolved into a cultural hub. Laws stipulate that Medellín’s major utility provider, EPM, must plow about a third of its profits back into the municipal government. This windfall has fueled all sorts of civic initiatives, including a cultural center called Casa Kolacho, named after a local hip-hop artist who was murdered. As I ascend into Comuna 13’s steep hills, I pass a dizzying assortment of larger-than-life street murals painted by local artists. One striking example depicts a woman with an entire terraced neighborhood—characteristic of the city—sprouting from her head. “We have a big-time artist movement going on right now,” Rendon says. “That opens up the doors for kids to get out of the streets.”

Walking around Comuna 13, with its transformed physical and moral landscape, it’s tempting to agree that maybe the past is best left alone. It’s easy to say that clear-eyed remembrance and wrangling with the moral failings of the past is somehow cathartic, like eating your vegetables. But that’s not always the case, according to David Rieff, a global policy analyst and author of In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and Its Ironies. Rieff writes that collective memory weighted with trauma can lead “to war rather than peace … and to the determination to exact revenge rather than commit to the hard work of forgiveness.” And that’s not even considering the very personal pain and loss many Colombians feel when Escobar even comes up in conversation. “You can say people have to remember,” Van Broeck says, “but who has to remember? They, or the tourists? Do [they] necessarily have to tell this story about the conflict, about the pain, to somebody outside?”

The experience of some countries underscores Rieff’s warning. In Germany, where swastikas are banned and World War II–era guilt is so thick you can breathe it in, far-right movements have sprung up, in part as an angry reaction to the weight of collective remorse. But it’s also possible to err on the side of forgetting. Francisco Franco’s forces killed more than 100,000 during and after the Spanish Civil War. It wasn’t until 2008 that Spain declared Franco guilty of crimes against humanity, and the lack of a sustained national reckoning or effort toward reconciliation has festered.

For Rendon, the Memory House and its communication of Colombia’s past is a fertile starting point for renewal, so long as it’s balanced with a fair accounting of the present. As one of Van Broeck’s Colombian interview subjects told her during her fieldwork on dark tourism, “We’ll reach the point … to have a tour that talks about our past, but include[s] the transformation. That’s how we will structure this past, which harmed us very much, but which also gave us so much strength to build [the] present we are building.”

At places such as La Catedral, the act of rebuilding speaks louder than any words. The monks’ chapel is built in a simple log-beam style. When we arrive, we are the only visitors, but most days, Rendon says—especially on weekends—the wooden pews are occupied by spiritual seekers, some of whom ascend along a harrowing bike path to get here. One of the icons at the altar is Maria Desatadora des Nudos (Mary, Untier of Knots), who also appears as a stone statue on the grounds. She’s a poignant choice, undoing earthly problems and—in some depictions—treading on a knotted snake representing the devil.

The entire outdoor space is blanketed in green and quiet. There are no car horns, no loudspeakers—scarcely even a human voice, since the monks live in seclusion. In the midst of such a sanctuary, it’s difficult to imagine what was once here. When Escobar arrived in 1991, he viewed the place as a sanctuary, too, safe from cartel foes and DEA agents. But his nature wasn’t about to change, and he soon began conducting new orgies of excess and violence. While still at La Catedral, he smuggled in two disloyal underlings, Fernando Galeano and Gerardo Moncada, and had his men torture and kill them. This grisly operation prompted the Colombian government to take over La Catedral, but as troops began storming the jail, Escobar fled.

These past horrors are undeniably present here, but evidence of atonement is on the terrace below the chapel, where the senior citizens’ residence is located. Looking down on its brightly-colored mosaic walls, tension recedes temporarily into the background. The site has been reimagined in the context of community, instead of the rogue pursuit of power and profit, and that gives it a kind of momentum. But the newly blank wall that once held the Escobar mural declares something else, too: that some kinds of renewal—some kinds of remembrance—may thrive best outside a villain’s shadow.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook