Medieval Africans Had a Unique Process for Purifying Gold With Glass

And scientists in Illinois have recreated it.

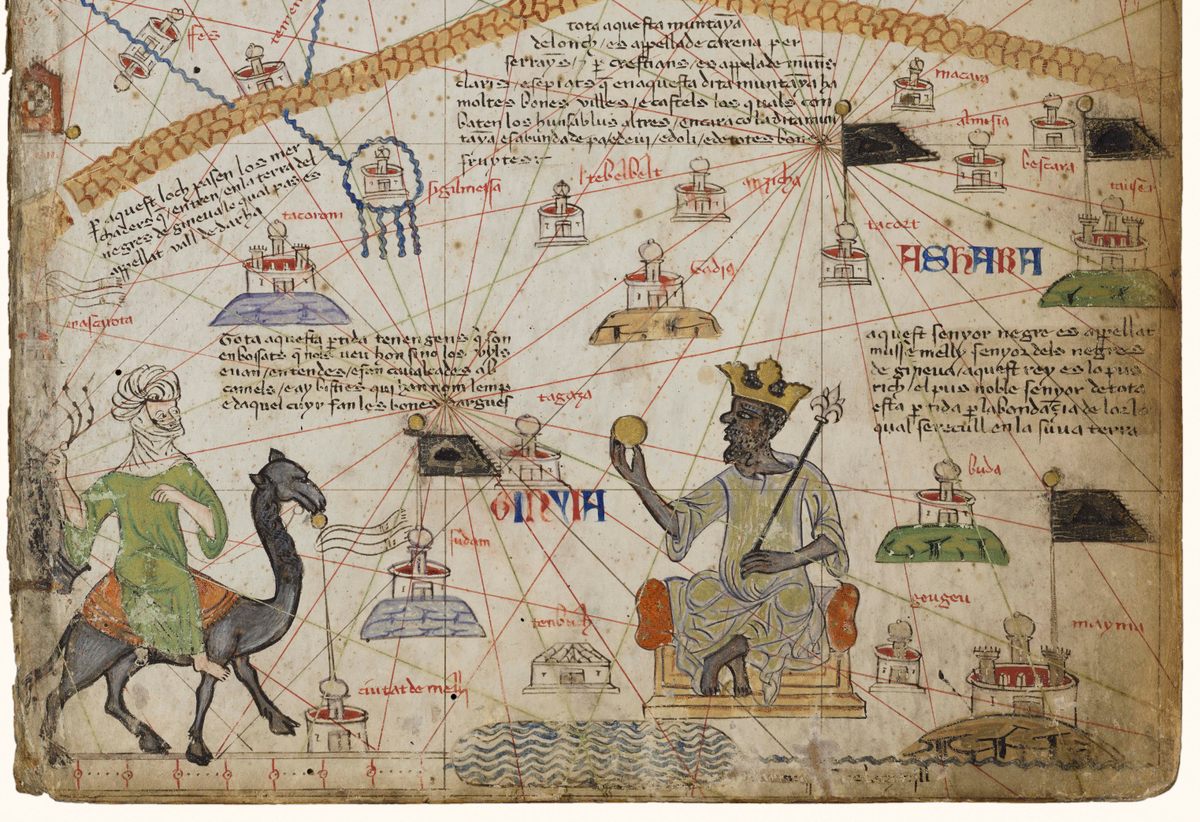

When Sam Nixon, an archaeologist with the British Museum, excavated ancient coin molds in Tadmekka, Mali, in 2005, it triggered a several-year exploration of how medieval Africans purified the gold they were using for their currency. Nixon had found little droplets of highly refined gold left over in the molds—which have been dated to the 11th century—as well as curious fragments of glass. Now scientists have recreated the advanced process behind the purification method they used then.

“This is the first time in the archaeological record that we saw glass being used to be able to refine gold,” says Marc Walton, codirector of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, a collaboration between Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago. “The glass appeared to be material that was [actually] recycled glass materials … so it really shows the industriousness and creativity of the craftsmen, who understood the properties of gold and glass enough to [use them for] this process of refining gold.” The recycled glass materials were remnants of broken vessels. Tadmekka was a town right in the middle of the trans-Saharan caravan route, so Nixon uncovered several types of material culture that had to do with trade, namely molds for “bald dinar,” or coins that hadn’t been stamped with the name of a mint (or a 10th-century equivalent of one).

According to Walton, Europeans in the 10th and 11th centuries purified their gold through cupellation, a process in which lead is mixed with gold laced with impurities, and then heated in a furnace until the droplets of purer gold can be skimmed off. But in the case of medieval West Africans, “They were taking the ore and other raw materials from the river and mixing it with glass,” says Walton. Since gold is inert, it doesn’t fully dissolve into melted glass, while impurities and other materials do, making this “a really novel way of using recycled glass material.”

Walton’s team at the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts replicates a lot of ancient technologies. To get to the bottom of how medieval Africans purified gold so successfully, they also made do with what their environment provided them. “We bought gold dust from a chemical supply company and then we mixed it with local Lake Michigan sand and then we made our own synthetic glass,” says Walton. “We heated it up, were able to dissolve the minerals in the sand, and were left behind with gold.”

Though Walton and his team updated this small-scale, bespoke process for purifying gold to modern times and adapted it to their environment in Illinois, their results show that the medieval Malian technique was both clever and sophisticated.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook