Meet the Father of Modern Space Art

Chesley Bonestell knew what he was doing.

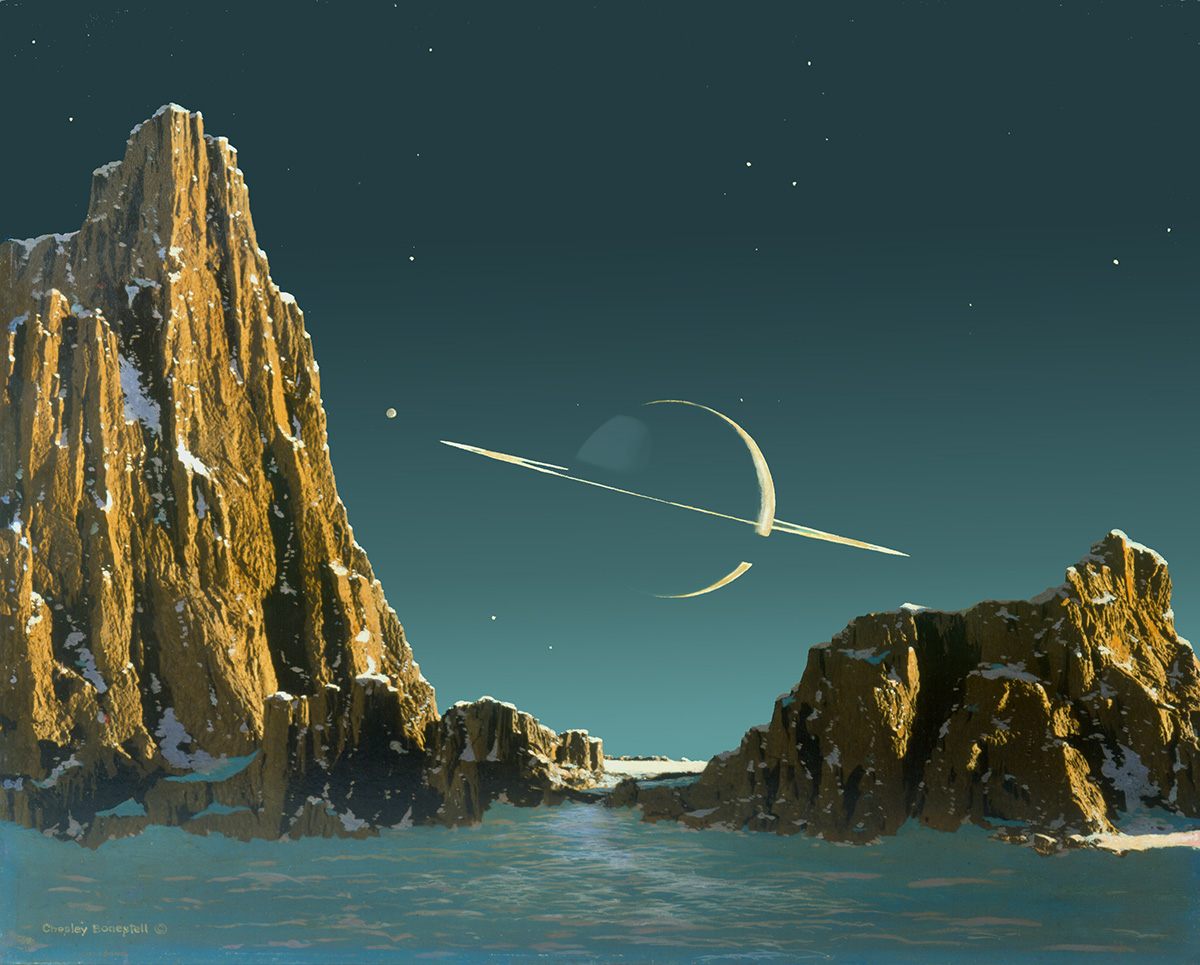

Saturn as seen from Titan, 1944 (Photo: Reproduced courtesy of Bonestell LLC)

Twenty-five years before Neil Armstrong set foot on the lunar surface, Chesley Bonestell showed humanity a view from Saturn’s moon. The image, which showed Earth as a distant speck—or was that just another star?—was an astonishingly beautiful painting titled Saturn as seen from Titan.

Space art had been seen before, but never as cinematically as this. The painting, published in Life, was a sensation, and the man behind it would go on to paint many more inspiring images of the as-yet-unexplored universe.

Saturn as seen from Titan combined Bonestell’s long-standing passion for astronomy with his experience as an artist for the silver screen. Born on New Year’s Day in 1888, spending his childhood years in San Francisco and looking up at the stars and drawing what he saw. Once, he went to an observatory in San Jose and saw Saturn. Then, as a teen, he drew it.

After attending Columbia University, and leaving without a degree, Bonestell became a working architect, contributing to the Chrysler Building and the Golden Gate Bridge. Before he turned his talents to space art, Bonestell was a matte artist, painting backgrounds for a string of movies in Hollywood’s golden age. In our current era of special effects, the art of matte painting is a bit forgotten, but for decades, until at least the late 1990s, it was essential to Hollywood filmmaking. The Death Star’s laser tunnel, the Statue of Liberty emerging from the sand in Planet of the Apes, the city of London in the background to a gliding Mary Poppins: all of these were matte paintings.

Bonestell churned out mattes for every major studio in Hollywood, at a time when they were an essential and cost-effective way to build scope. His work can be seen in such cinema classics as 1939’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and 1941’s Citizen Kane. (That wide shot of Xanadu? That’s Bonestell).

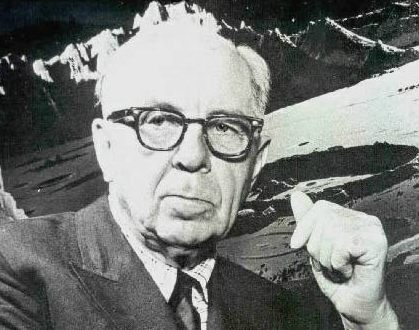

Chesley Bonestell (Photo: Wikimedia)

Nearly 40 years after drawing Saturn as a teen, Bonestell drew it again. But this time it wasn’t from the perspective of the Earth, but from Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Bonestell submitted the image, unsolicited, to Life magazine. It was published in the May 29, 1944 issue, along with several other Bonestell paintings. Life then was an American institution, with a circulation well over a million, and Bonestell’s work hit the public “like an atomic bomb,” Bonestell biographer Ron Miller wrote.

How did Bonestell do it? As Miller writes, Saturn was meticulously planned. Bonestell’s process started with a sketch, and then a real-life model, which he photographed, enlarged, and used to paint the artwork. As it turned out, the science of the painting was wrong—you’d likely see nothing but a thick haze if you were actually standing on Titan, not a clear view of Saturn—but that hardly mattered. The image blew up.

Bonestell would go on to publish dozens more paintings in various magazines, science fiction or otherwise. In 1949, many of those paintings were compiled into a book: The Conquest of Space, which showed, in 58 illustrations with near photo-realistic detail, astronauts actively exploring our solar system. (That book also helped inspire a movie of the same name.)

In 1952, there came an influential series in the now-defunct magazine Collier’s, just before Congress was beginning to think about how to fund the space program. Five years after that, the Soviets launched Sputnik, and the Space Race was on. It’s hard to say with any certainty just how influential Bonestell’s paintings were in initiating humans’ drive to shoot for the stars, but his artwork certainly made an impact on those dreaming of space travel.

“Chesley Bonestell not only changed my life,” G. Harry Stine, the creator of amateur model rocketry once said, “but motivated two generations of people to start the human race on its way to ultimate freedom of the stars.”

The early 1950s, for Bonestell, was one of the most productive of his career. He produced space painting after space painting, depicting imagined parts of the universe in all its forms, in addition to man’s (then still-hypothetical) attempts to explore it. Look, there’s a colony on Mars! And, look, the surface of Mercury! And here we have the assembly of “moonships” above Hawaii!

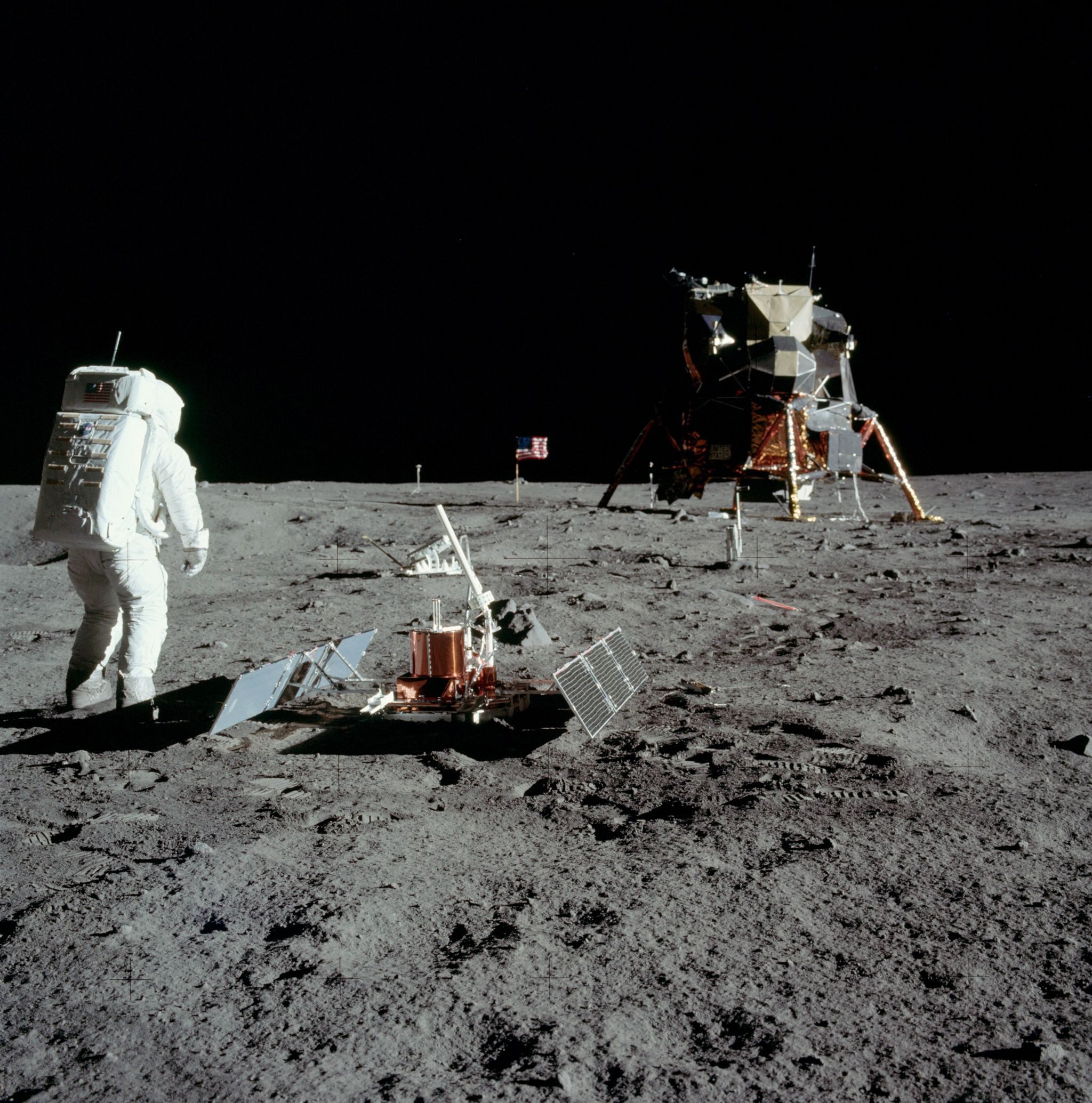

Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon. (Photo: Neil Armstrong/Public Domain)

How accurate were these paintings? Bonestell got a few things right; he seemed to know, for example, the importance rockets would have in space travel, in addition to how rockets would burn in stages before separating. And his lunar landers were also reasonably realistic, for having been imagined in 1951. Elsewhere, though, he missed the mark, as with his depiction of a circular space station, or a “baby satellite,” that, for some reason, still has a rocket nose cone attached.

Still, Bonestell, who died in 1986 at the age of 98, was an exacting and demanding artist and collaborator, sometimes clashing with those who questioned his vision. He complained bitterly, for example, to the director of 1955’s Conquest of Space that the movie’s landscape of Mars, a smoothed-out panorama of red dust, was not craggy enough. (The director’s vision, in fact, turned out to be closer to reality.)

“My file cabinet is filled with sketches of rocket ships I had prepared to help in his artwork—only to have them returned to me with penetrating, detailed questions or blistering criticism of some inconsistency or oversight,” Wernher von Braun, who collaborated with Bonestell on the Collier’s series, once said. “I have learned to respect, nay, fear, this wonderful artist’s obsession with perfection.”

Bonestell is generally credited as the father of modern space art, but he definitely wasn’t the first. That title goes to Lucien Rudaux, a French astronomer and space art enthusiast who Bonestell discovered in London in the 1920s, when Bonestell was still a relatively unknown illustrator. But Rudaux’s paintings of the Moon, made in the 1920s and the 1930s and compiled into a book called Sur les Autres Mondes (On Other Worlds), might have just been too realistic. While Bonestell’s Moon contained dramatic peaks and valleys, Rudaux’s were more restrained, reflecting a surface of the Moon that Rudaux rightly expected was closer to the real thing.

“Rudaux’s lunar landscapes might have been more correct scientifically,” Ron Miller wrote in Melvin H. Schuetz’s A Chesley Bonestell Space Art Chronology (1999), “but they were also, unfortunately, as boring-looking as the Moon itself turned out to be.”

In the 1960s, when Bonestell finally saw pictures of the real thing, he was disappointed.

It looks, he said, according to Miller, “for all the world like the Berkeley Hills.”

This article has been updated to clarify the author of A Chesley Bonestell Space Art Chronology.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook