Mumbai’s Students Take to the Streets—to Study

In India’s biggest city, schoolwork can be easier to do on quiet public corners than in loud, cramped apartments.

“This is my second home,” says Kasim Motorwala, pointing proudly at the S.K. Patil Udyan (Study Garden) on Charni Road in Mumbai.

Barely 650 feet away from a noisy railway station, the semicircular 70-seat enclosure is a bastion of calm and quiet. Students bend over books or compare class notes in a hushed huddle, backpacks bulging with thick volumes on engineering, law, or statistics. The study area they’re seated in, next to a public garden, is equipped with a plastic canopy, water dispensers, and ceiling fans to beat the sticky heat.

Motorwala, a 22-year-old law student who works part time, has spent many long nights studying here, battling mosquitoes, sleep, and humidity. “I came here during [my] three years of college, pulling all-nighters during exams,” he says. “It’s a necessity for students like us who come from small homes.”

The uncomfortable, metal-backed chairs at S.K. Patil do a good job of keeping you awake, says Hemantkumar Jain, a former student who now works in Dubai as a change-management consultant. A sign on a wall spells out the rules: No loud talking, no charging electronic devices, no mobile phones off silent mode. The calm is broken only occasionally, by the barking of stray dogs.

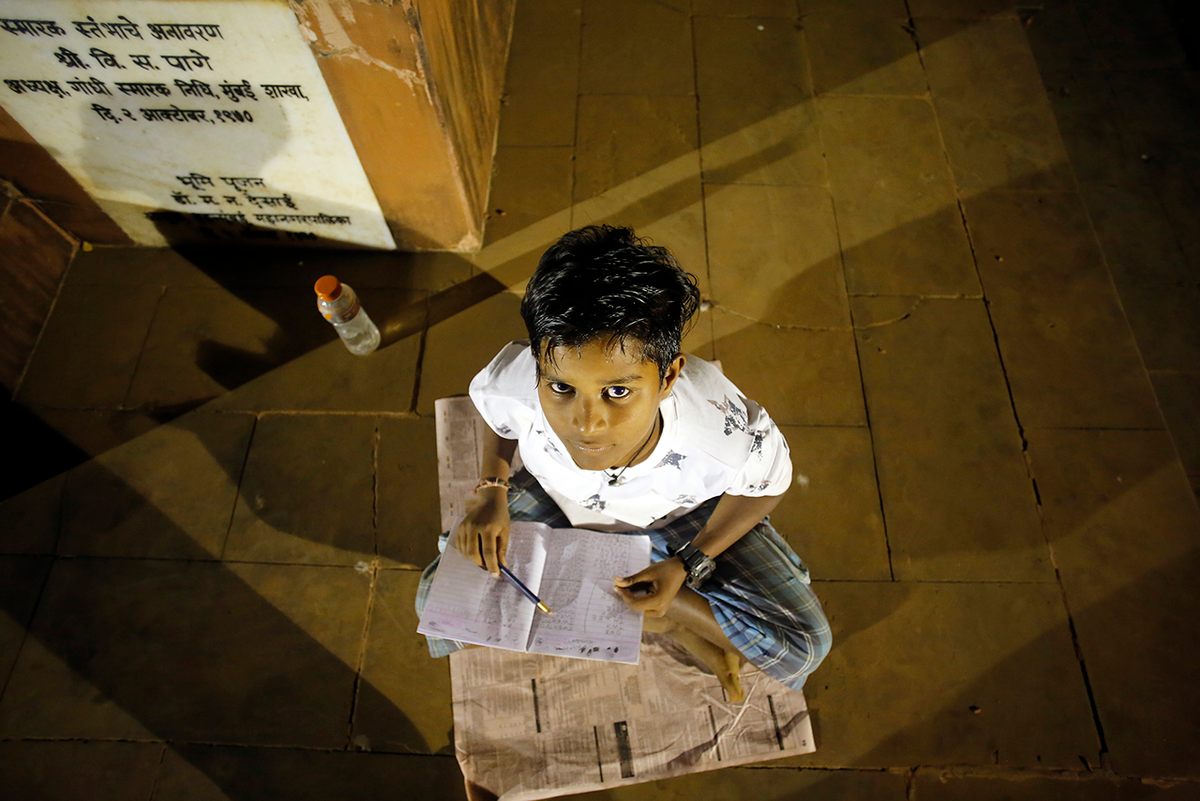

“Study corners” like S.K. Patil are a product of Mumbai’s biggest problem: lack of space. Sixty percent of the city’s 18 million residents live in chawls—cramped, low-income housing where rooms no larger than 200 square feet hold families of four or more. Filled with the buzz of television, the clatter of utensils, and the bawling of children, they’re challenging places to do schoolwork.

That prompts many high-school and college students who live in chawls to seek the quiet of study corners—public spaces where, paradoxically, it’s easier to concentrate on academics.

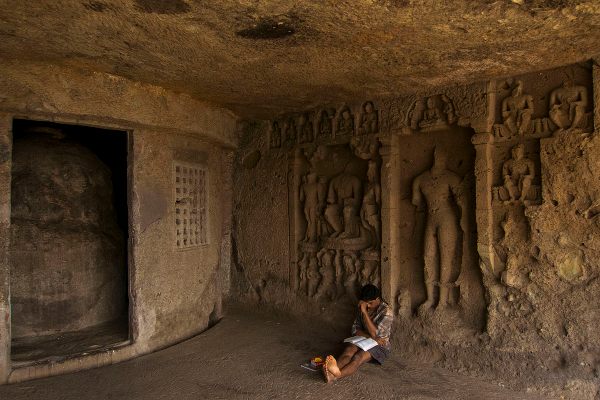

Most of the city’s study corners are adjacent to public parks and gardens. But only a few of these spaces appear in official city records. Their history is mostly anecdotal, and no one is quite sure when students started using them as study halls.

Abhyas Galli—“Study Lane” in Marathi, the local language—is located near Worli Naka, a busy junction in central Mumbai. Locals say this side street has been used for studying since the early 1930s, after the Bombay Development Department set up chawls for textile mill workers nearby.

As study corners have become more popular among Mumbai’s students, civic authorities, charitable organizations, and local politicians have started renovating some of them—installing new tube lighting, for instance, or fitting them with charging stations.

Abhyas Galli is one of those corners. “The walls were painted recently,” says Samir Yadav, “and during exam time, [a] local politician distributes tea and biscuits free of cost.” Yadav and his Grade 12 classmates Ayush and Akshay Pawar have been studying here for four years.

Still, at most study corners, facilities are rudimentary—or nonexistent. Abhyas Galli lacks even a toilet. The bright halogen lights set up by Mumbai’s electricity board cover only one side of the pavement. And there are just a few wooden benches, forcing studying students to squat on mats made out of old banners.

Despite the scant amenities, Mumbai’s study corners are filled nearly year-round, save for the monsoon-battered months of June, July, and August. Students are driven to these places both by their individual study needs and by the motivation that peer support can provide.

Mahendra Devasi, 18, shares a one-bedroom apartment with his parents and siblings. As he preps for a medical-school entrance exam, he finds studying in a group to be enormously beneficial. “Sometimes [at S.K. Patil] we find people who have cleared the same test and can give good tips.”

Raj Janagam, 31—who studied at Abhyas Galli from 2003 to 2005 and is now an entrepreneur in India’s tech capital, Hyderabad—agrees. “Group study helped me find focus,” he says.

For many students in Mumbai, study corners also make good financial sense. Not everyone can afford the fees at the city’s libraries and reading rooms. An annual membership might cost the equivalent of anywhere from $20 to $80.

There are reading rooms too—some free, others that cost $3 a month—but most of them close by 7 p.m. Spots like Abhyas Galli, however, are available 24/7. And while most public gardens in Mumbai close by 9 p.m., the study corners adjacent to them usually stay open, with security guards employed by the city patrolling the areas to keep miscreants away.

The late hours also help part-time workers like Motorwala. “I can come after work and dinner and continue until midnight,” he says.

He proudly shares several success stories he’s heard—class valedictorians who have studied at S.K. Patil, and graduate and postgraduate students who have cleared hard-to-pass entrance exams for professional courses in medicine, engineering, or chartered accountancy.

Study corners can even help students find a benefactor. Ghulam Jilani Quadri, now a doctoral student in the United States—he studies computer science at the University of South Florida in Tampa—used to study at P.T. Mane Garden, in the Nagpada section of south Mumbai. The Educational and Welfare Foundation, a charitable organization that supports economically disadvantaged students and has administered the study corner since 2005, recently sponsored Quadri, paying his grad-school application fee and other educational expenses.

Aziz Makki, the president of the organization, says the garden—an unofficial study corner long before its renovation by the foundation, which installed a new roof and water fountain—has produced two doctors and almost 80 engineering students.

What it hasn’t produced yet is gender equality. Though there are usually several girls at any given study corner in Mumbai, there are usually at least twice as many boys. The girls are at a time disadvantage too: They have to quit studying and head home at 9 p.m., for safety reasons. But at S.K. Patil—once a male-only study corner—boys can stay till midnight. In some places they can stay all night.

That 9 p.m. curfew gives 23-year-old Aarti Dighe, an aspiring chartered accountant who works part time, barely enough time to do her schoolwork each night. But she’s grateful for the time she does have each evening at S.K. Patil. Away from her noisy neighborhood and tiny apartment, where her grandmother blares televised religious sermons at full volume, Dighe finds the space, solace, and succor she needs to succeed academically.

So do many other students in Mumbai, reaching for greater academic heights and a brighter future in India’s largest, wealthiest city.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook