Don’t Just Wipe Your Face—Write a Poem!

A recently resuscitated online literary journal is dedicated to the humble napkin.

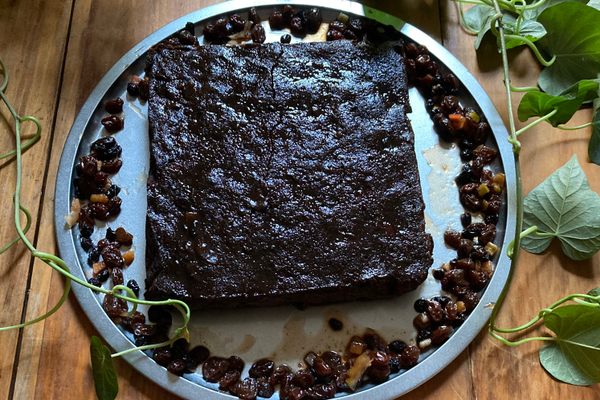

If you’ve got too much soup in your bowl, you’ll likely end up reaching for a napkin. But if you have too many ideas in your head, you probably will, too. That’s what napkins are there for: to mop up excess thoughts, scribbles, ideas, and emotions, along with more physical drips and dribbles. A Twitter-only publication, The Napkin, celebrates the wipe’s rich creative potential, publishing poetry, diagrams, short stories, sketches, and other ephemera, all done solely on napkins.

Jordan Davis—who first started The Napkin back in 2014, and resuscitated it a few weeks ago—has a special appreciation for the way a napkin, as he puts it, “makes you put things down in a small square quickly without fussing too much over it.” While some people have made careers out of bringing true beauty and care to napkin art, successful submissions to The Napkin are generally quick and dirty. “The small space, the haste—all of that appeals directly to my aesthetic,” Davis says.

From the remarkable @MrBikferd pic.twitter.com/vq3JHlqhao

— The Napkin (@thenapkinletter) September 4, 2015

He’s not the only one. In certain circles, napkin-related origin stories are basically a badge of honor. As Davis points out, “dozens and dozens of startups have claimed to have been founded on the back of a napkin.” The first four Pixar movies, the Super Bowl trophy design, the Laffer Curve, and Southwest Airlines all allege a similar provenance.

The Napkin originally leaned into this egalitarian spirit. Back in 2015, when there was also a newsletter, they published napkins containing everything from illustrated translations to advice for reading the news. In this more recent incarnation, Davis—a poet himself—has decided to focus more on verse (although “we are open to everybody,” he says). Authors range from newcomers to big names: Last week, they published a meditation on thrift-store shopping, written in ballpoint on a creased paper napkin by Pulitzer Prize winner Rae Armantrout.

Davis himself has had a rollercoaster relationship with napkin-writing. Back when he first started the publication, “I bought a big bag of Vanity Fair fancy dinner napkins, and tore them to shreds with pens that were wrong,” he says. (He now recommends the Pilot Razor Point II.) But even with the right pen, he found himself ripped up by the pressure of expectation. “I started to get napkin block,” he says. “I was writing things that felt like I had rehearsed them. I defeated the purpose of it.”

In his current, more curatorial role, Davis has his eye out for trends. Although he stresses that thus far, his sample size is too small for anything but back-of-the-napkin analysis, “I would guess that the crummier the napkin paper quality, the more urgent the message will be,” he says. “That’s probably a romantic idea. But I am romantic about crummy napkins.”

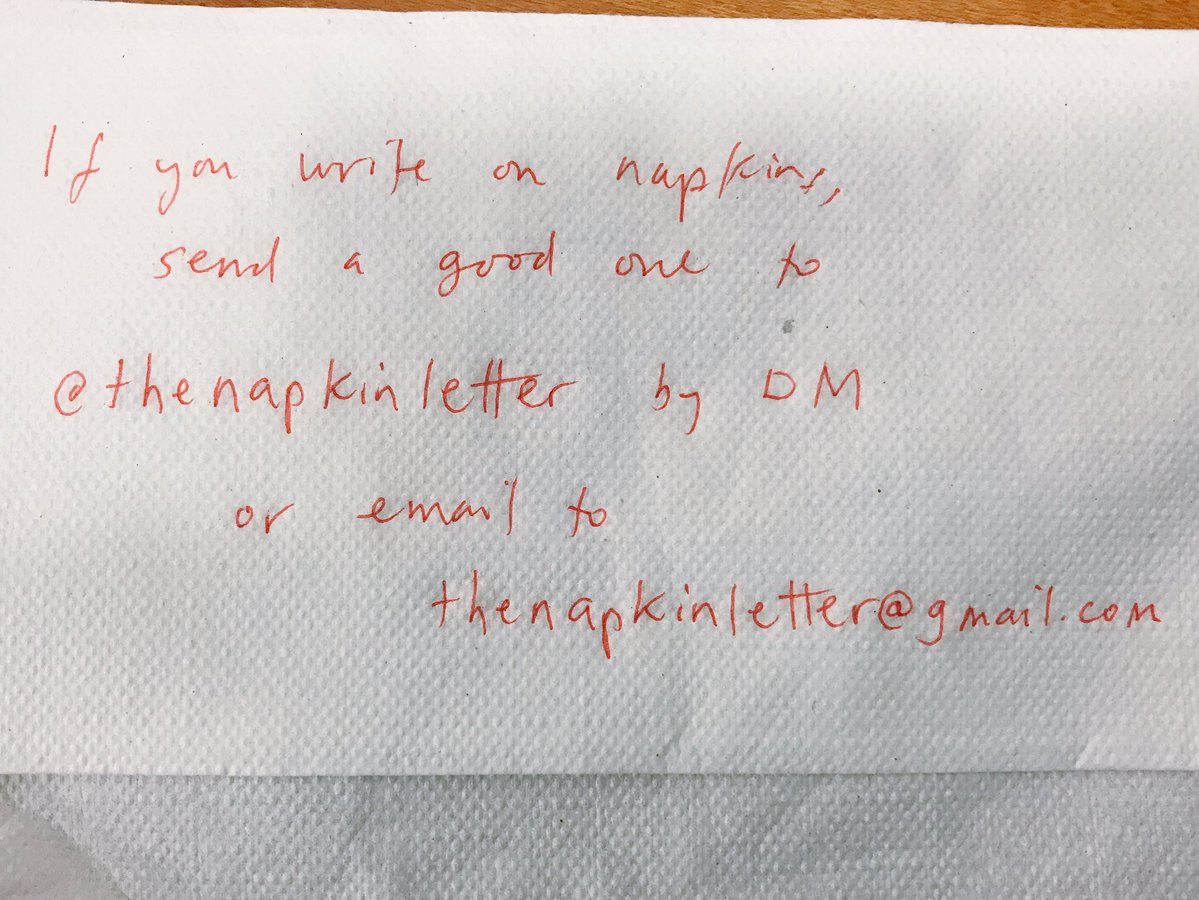

This romance only goes so far: At this point, “we would prefer not to receive napkins in the mail,” Davis says. Instead, mealtime scrawlers can submit their works via email, as laid out below:

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook