The Earliest European Cave Art Was Made by Neanderthals

A new study suggests that they had the capacity for symbolic behavior.

For decades, Neanderthals have been burdened with a bad rap. Maligned as thick-skulled and dim, having brute force to Homo sapiens’s sharp wit, their extinction around 40,000 years ago has often been seen as “survival of the fittest” in action. In short, we won. But more recent archaeological research tells a different story. Like humans, Neanderthals buried their dead. They may have grieved. They likely had a language all of their own—certainly, they had the physical capacity. They hunted, made pigments, used toothpicks. They were enough like us that, in some cases, we had children with them. And around 64,000 years ago, in what is now Spain, they made abstract art on the walls of caves.

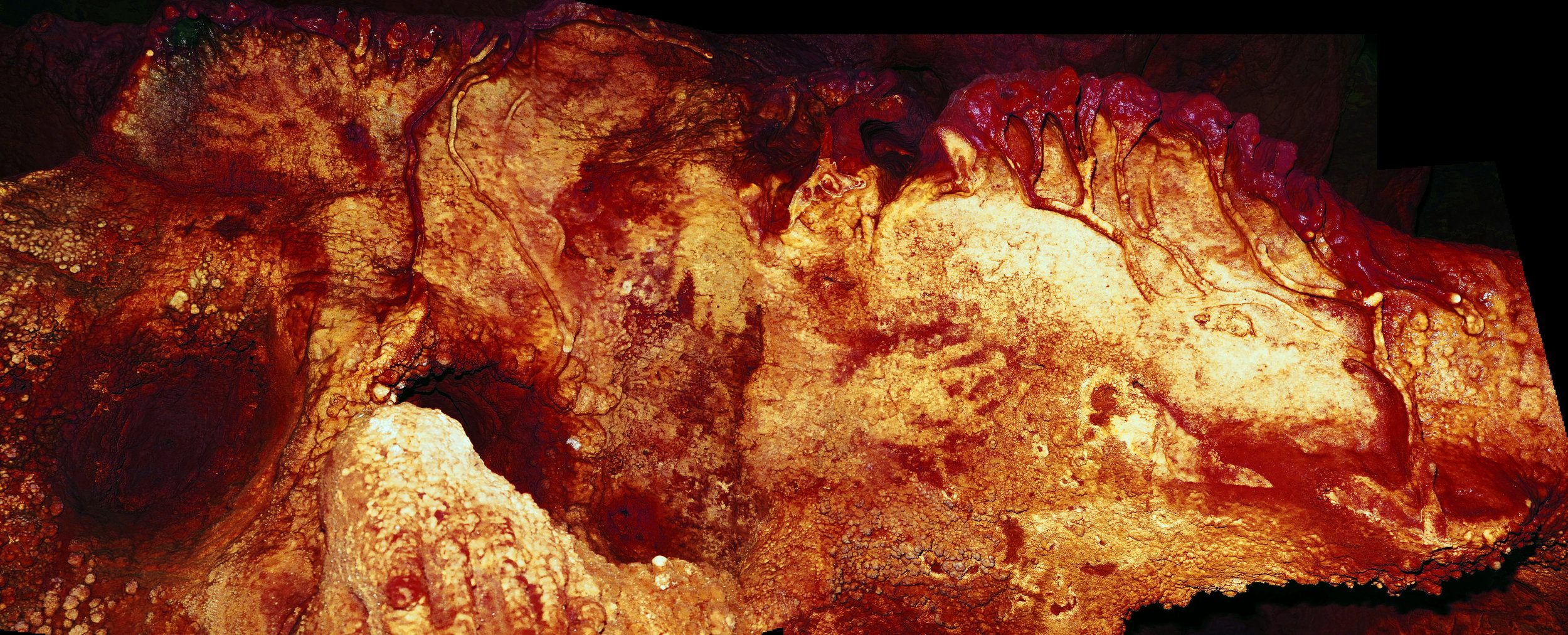

The whorls and slashes of this art, found at three sites up to 430 miles apart at La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Ardales, had previously been attributed to early humans. But a new study, led by researchers from the University of Southampton and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, used a technique called uranium-thorium dating to date the works. At a minimum age of 64,000 years old, the art—stenciled hands, dots, pictures of animals and geometric signs—predates modern humans’ arrival in Europe by 20,000 years. At that point, the land was inhabited only by Neanderthals.

The results of the study were published earlier this week in the journal Science. The greatest takeaway, researchers said, is that the artwork suggests that Neanderthals, like modern humans, had the capacity for symbolic behavior. In turn, it raises new questions about how we should think about our ancient neighbors.

“The emergence of symbolic material culture represents a fundamental threshold in the evolution of humankind,” joint lead author Dirk Hoffmann said in a statement. “It is one of the main pillars of what makes us human.” That these works appear in three separate places is equally significant, and suggests that it was a long-lived tradition, co-author Paul Pettitt added. “Neanderthals created meaningful symbols in meaningful places. The art is not a one-off accident.” Whether other early cave art was also misattributed to modern humans is yet to be seen, he said.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook