Why Thousands of New Animal Species Are Still Discovered Each Year

The spider ‘Cebrennus rechenbergi’ cartwheeling down a sand dune in Morocco (Photo: Ingo Rechenberg/ WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The spider ‘Cebrennus rechenbergi’ cartwheeling down a sand dune in Morocco (Photo: Ingo Rechenberg/ WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Every spring, the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry releases a list of the top ten new animal discoveries, and this year’s is a great one, including a chicken-like dinosaur, a spider that cartwheels into any predator dumb enough to threaten it, and a nine-inch-long walking stick insect.

Luckily, even after 250 years of professionals documenting thousands of new plants and animals every year, the rate at which new species are discovered remains relatively stable. Somewhere between 15,000 and 18,000 new species are identified each year, with about half of those being insects. However, that number is somewhat misleading: it also includes the correction of taxonomic mistakes, movements from one family to another, and decisions that will end up being overruled in years to come.

The new species are scattered all over the globe, with animals from the top ten list hailing from Morocco, Australia, eastern China, central Mexico, and elsewhere. But where would you go if you wanted to find a brand new animal species?

The ‘Anzu wyliei’ dinosaur, dubbed the “chicken from hell”, discovered in North and South Dakota (Photo: Mark Klingler/Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

The ‘Anzu wyliei’ dinosaur, dubbed the “chicken from hell”, discovered in North and South Dakota (Photo: Mark Klingler/Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

There are many scenarios that can lead to a new species being discovered. The archetypical researchers clad in multi-pocketed khaki clothing heading into the jungle certainly do locate new creatures, but they’re not the only ones.

“There are cases of new species being found in museum collections, where they were collected 50 or 100 years ago and at the time nobody looked at the specimens closely enough,” says Christopher Raxworthy, a curator in the herpetology department at the American Museum of Natural History, who frequently goes out on fieldwork expeditions to look for new reptiles and amphibians.

Technology has led to even more animals being identified. New species today are regularly detected through DNA. Often, two species live relatively near to each other and look exactly alike, which means they were formerly categorized as only one genus. But analyzing their DNA shows enough dissimilarities in their genes to now classify them as separate species.

Zoologists at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. actually spent years being frustrated about their resident olinguitos’ inability to mate. But the olinguito is a small carnivore in the raccoon family, commonly confused with its identical-looking cousin the olingo. They were trying to mate the olinguito with an olingo, not realizing that it was an entirely different species.

An Olinguito (above) not to be confused with an Olingo (below) (Photo: Mark Gurney/WikiCommons CC BY 3.0)

(Photo: Jeremy Gatten/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

That doesn’t mean the well-explored parts of the world have no surprises left for us: just last year, a new species of frog was discovered in New York City, of all places. However, if you want to discover a new animal, less-trodden areas are a better bet. The most rewarding spots tend to be the tropics, since there are a wider variety of plants and animals there than in temperate regions.

There are plenty of places in the tropics that haven’t been thoroughly sifted through, though. “Typically, if you were interested in finding new species, a very good thing to look at would be to understand where people have done research and surveys in the past, and then find the holes, the blank areas of the map that have been under-studied,” says Raxworthy.

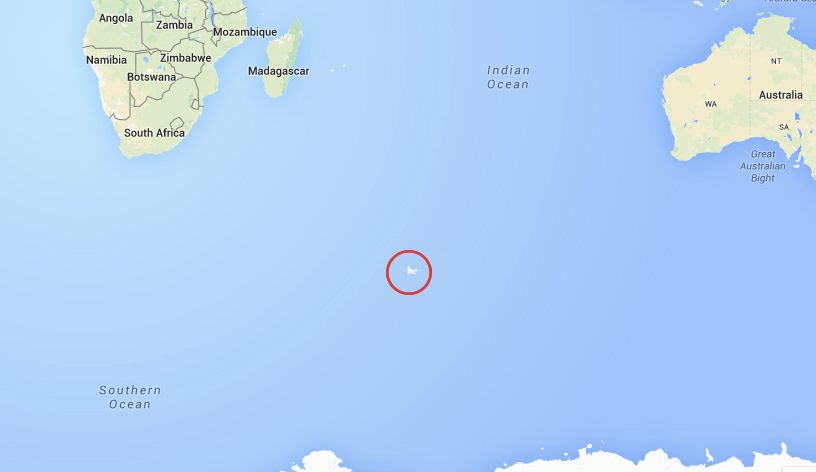

The reasons why some places remain unexplored are not what you would expect. Inaccessibility, for example, is not really a problem in the modern age. Sure, there might not be any direct flights from a research institution to Motuo, China (no roads go there) or the desolate Kerguelen Islands in the southern Indian Ocean (you can only get there with a six-day boat ride from an island off the coast of Madagascar), but that doesn’t bother contemporary researchers much.

The remote Kerguelen Islands are one of the most isolated places on earth, and lie more than 2051miles away from the nearest populated location (Photo: MapData © 2015 Google)

“People who really enjoy fieldwork, they enjoy exploration, so they’d be up for the challenge,” says Raxworthy. And with the relatively cheap cost of international travel (compared to decades past, at least), a geographically remote place wouldn’t discourage researchers intent on finding new species–it might even encourage them.

So if it’s not physical inaccessibility, why are there still blank spots on the map? “I think a lot of it is really driven by politics,” said Raxworthy. The political situation can unnerve researchers far more than a long and uncomfortable boat ride, and national and regional instability can lead to waves of scientists alternately heading to (or avoiding) large swaths of land.

In the next few years, for example, expect to see a whole clutch of new species emerging from Cuba. American or U.S.-based researchers have long been barred due to economic sanctions from entering the country. But with the loosening of travel restrictions, a new crop of scientists are lining up to visit. Raxworthy, a U.S-based Englishman, is hoping to head to Cuba to study the island’s reptiles and amphibians within the year, and he won’t be the only one.

Cuba is an extreme example; more often, areas become possible to explore in stages as they become more stable. “In Colombia, different regions of the country fall under the control of different drug barons,” says Raxworthy. “So one year you can go to this mountain and do work over there, and the next year that’s totally off limits and would be really dangerous to go there.” Tropical Africa falls along the same lines. Much of the Eastern Congo is frustrating for scientists, as it’s comparatively unexplored and likely to host a wide variety of new species, but dozens of warring factions make it an exceptionally dangerous destination.

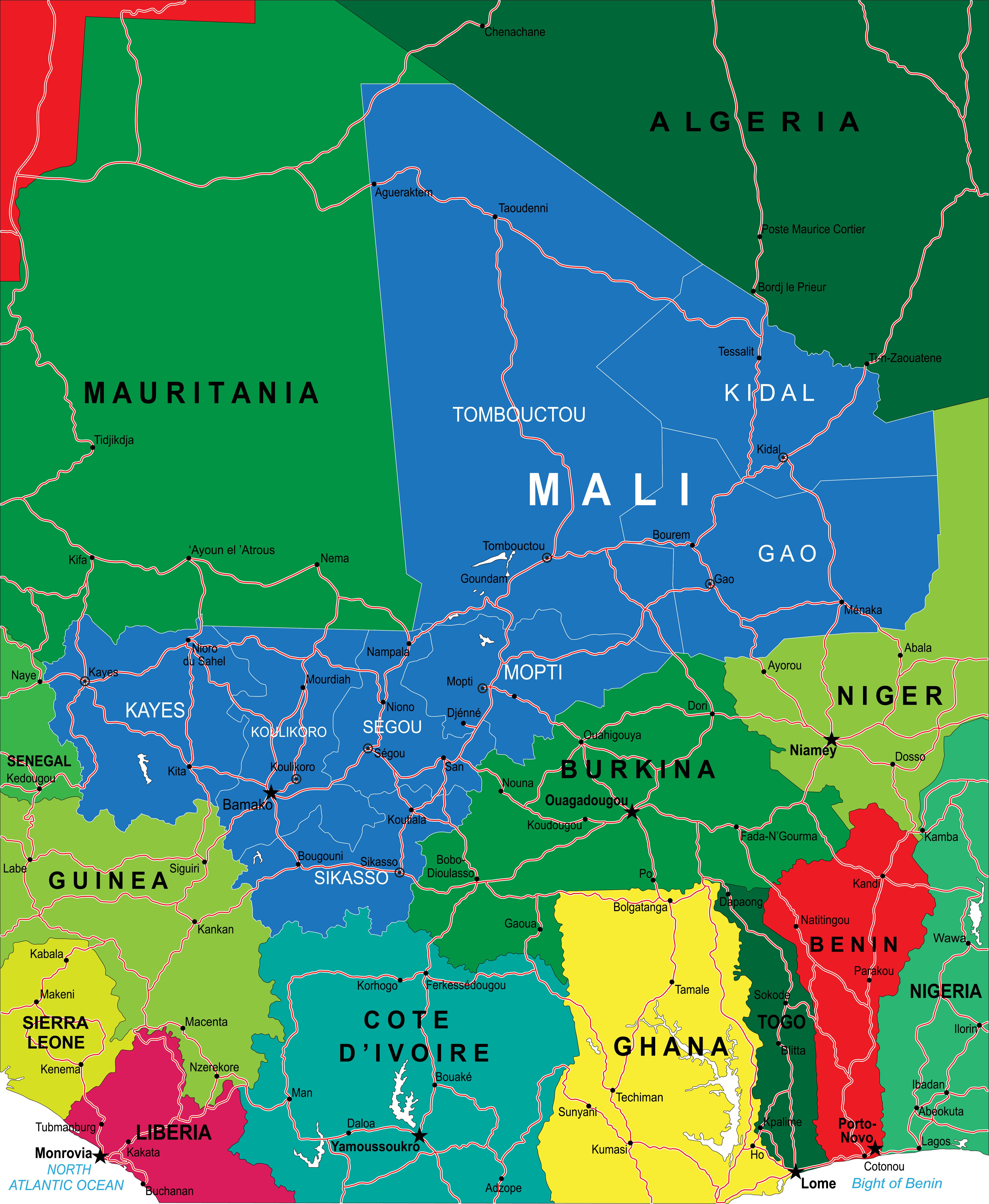

Then there are the parts of the world that, right now, are simply a no-go. “I think for example, if you wanted to do work right now in a place like Somalia, you’d be crazy,” said Raxworthy. Northern Mali, near Timbuktu, is also largely off-limits thanks to the high chance of getting kidnapped. Afghanistan would be another tough one. But stability comes in waves, and at some point, it’ll become more safe for researchers to head out there—and as soon as they can, they will, and we’ll start seeing more new discoveries from those areas.

A map of Mali, a potential area for new species (Photo: Serban Bogdan/shutterstock.com)

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled Dr. Raxworthy’s last name. We apologize for the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook