Found: A Greasy Leftover Snack Inside a Rare Book

Whether a cookie or a fruit bun, the “offending object” has been discarded.

Don’t judge a book by its cover—you might miss out on free, albeit fossilized, food.

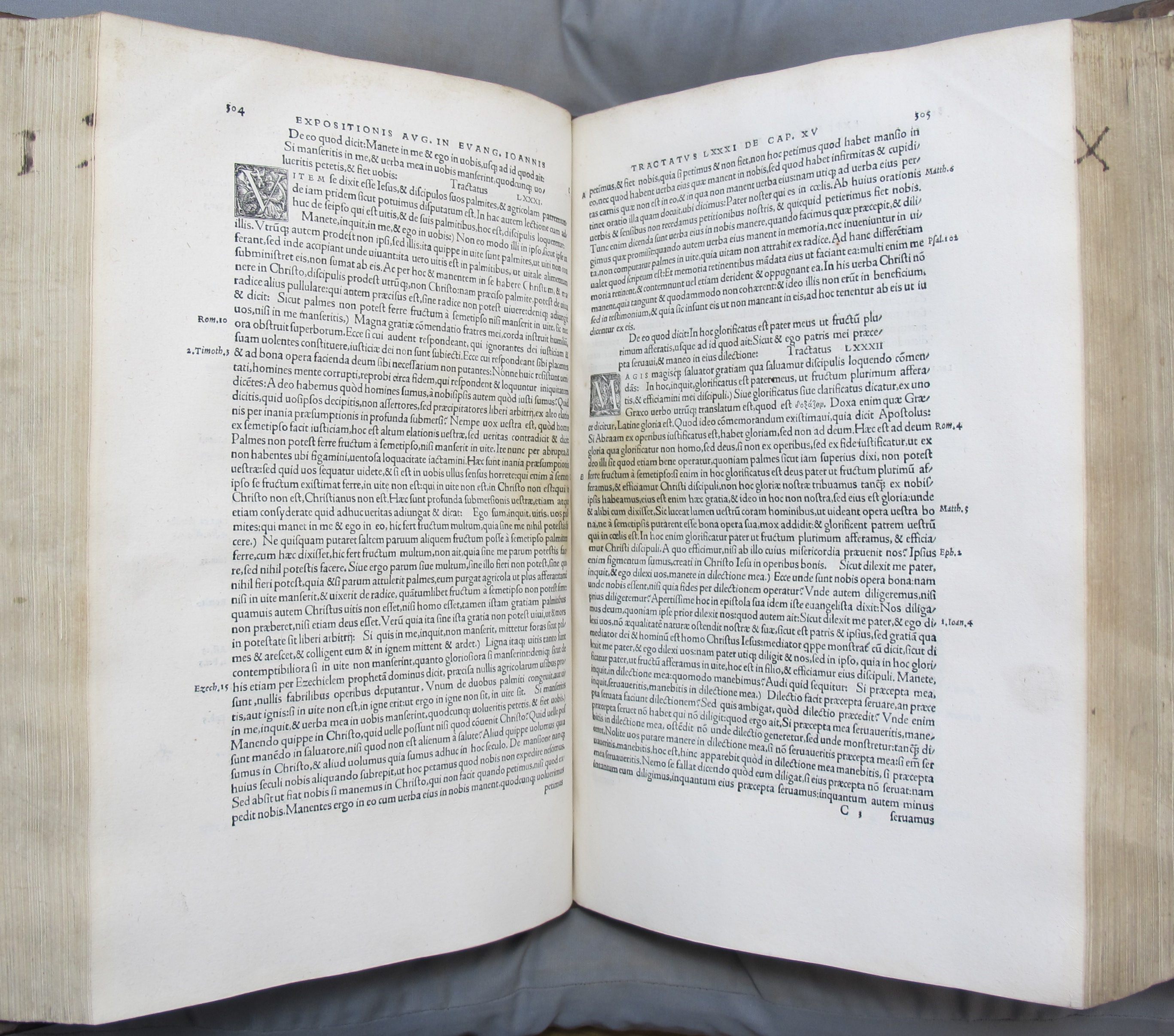

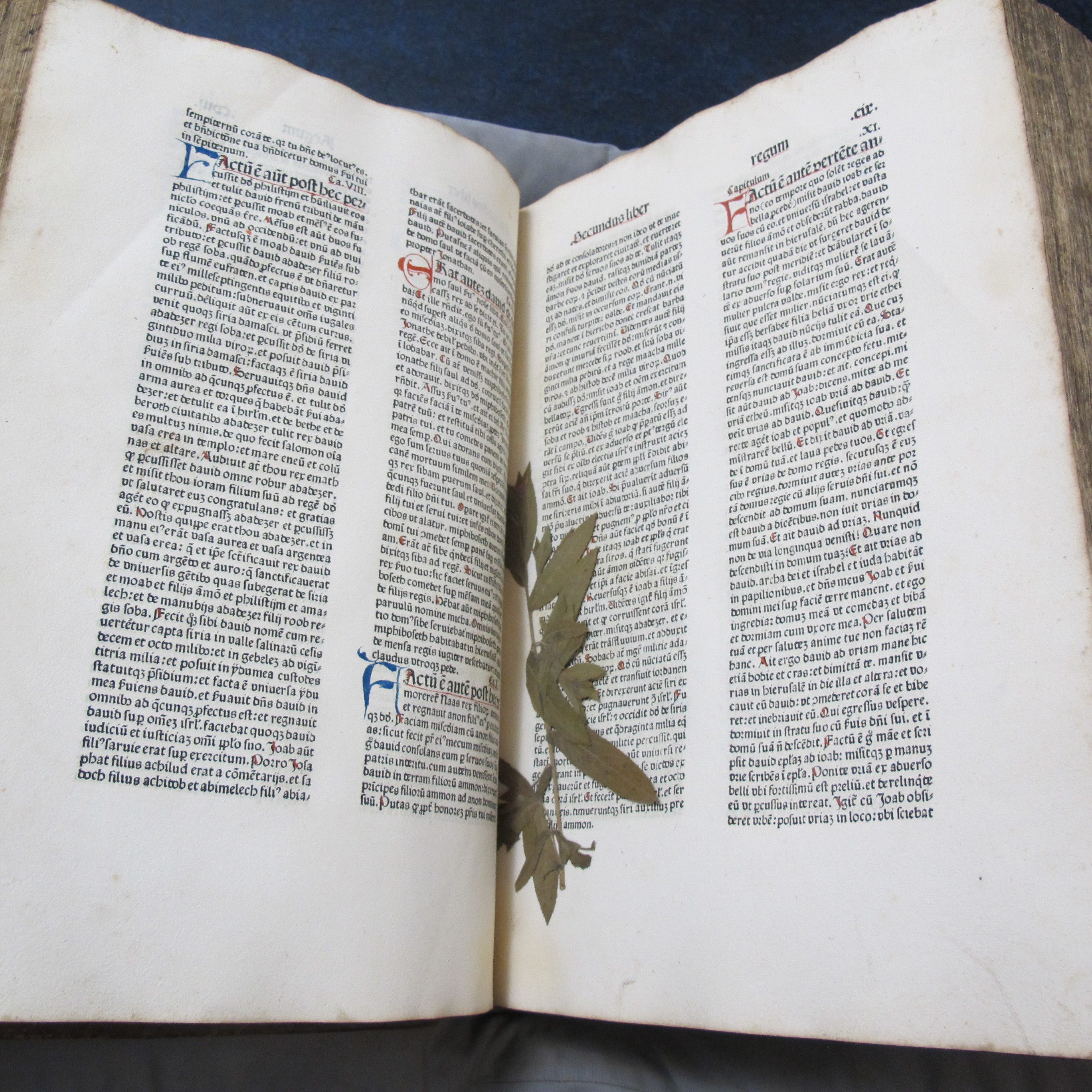

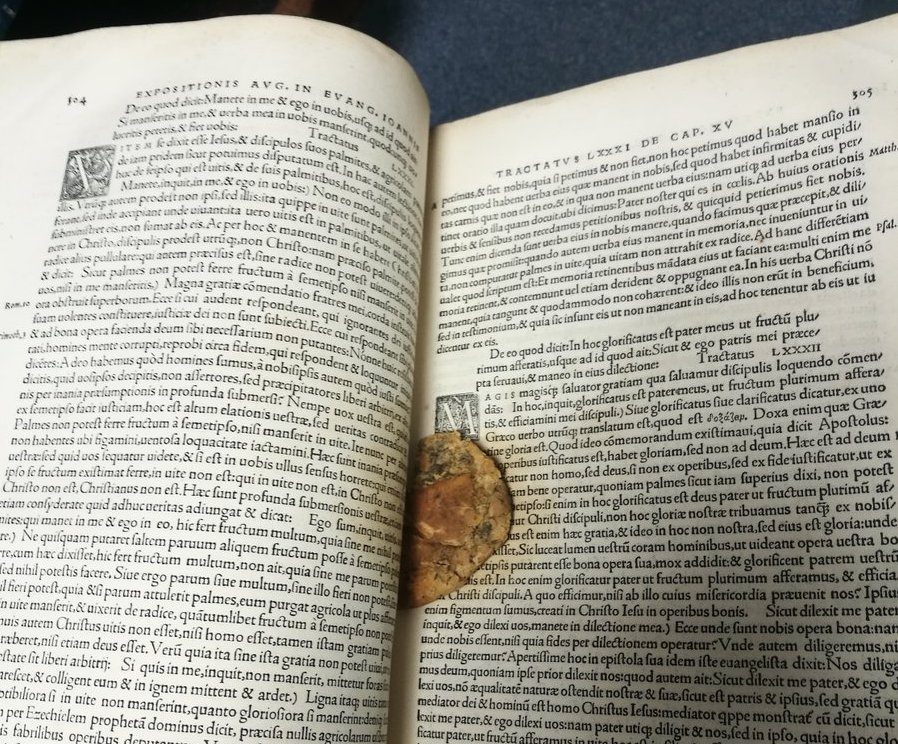

Emily Dourish, deputy keeper of Rare Books and Early Manuscripts at the Cambridge University Library, was recently making rounds through the collection when she made a most unusual discovery. Wedged inside a Renaissance-era volume of Saint Augustine’s complete works sat a flat, decaying, dry, partially eaten snack—likely a cookie, or “some kind of fruit bun,” though Dourish admits that the treat was well past easy identification.

Dourish had pulled the book off the shelf as part of an ongoing effort to add volume-specific details to listings in the library’s online catalog. The rare books collection, she writes in an email, contains about 1 million items, “so adding this information is something of a labour of love.” One perk is the opportunity to “make new discoveries” about the priceless and historic editions, though those findings generally aren’t edible.

It’s impossible to know for sure how the snack ended up in the book, though it’s safe to assume it didn’t happen during its publication in Switzerland, between 1528 and 1529. Dourish’s working theory is more modest. Cambridge, she writes, acquired the book from a local boy’s school that was founded more than 450 years ago. In 1970, the school donated some 800 historic titles to Cambridge, where “environmentally controlled book storage” can keep older materials in better shape. “We are confident,” she writes, “that our reading room staff would not have allowed someone to drop food into the book while consulting it in this library!” She believes it’s likelier that the snack got lodged in the book during its days at the school, where “it’s quite possible that a schoolboy could have had a snack.” Ultimately, the treat’s origins will have to remain a mystery.

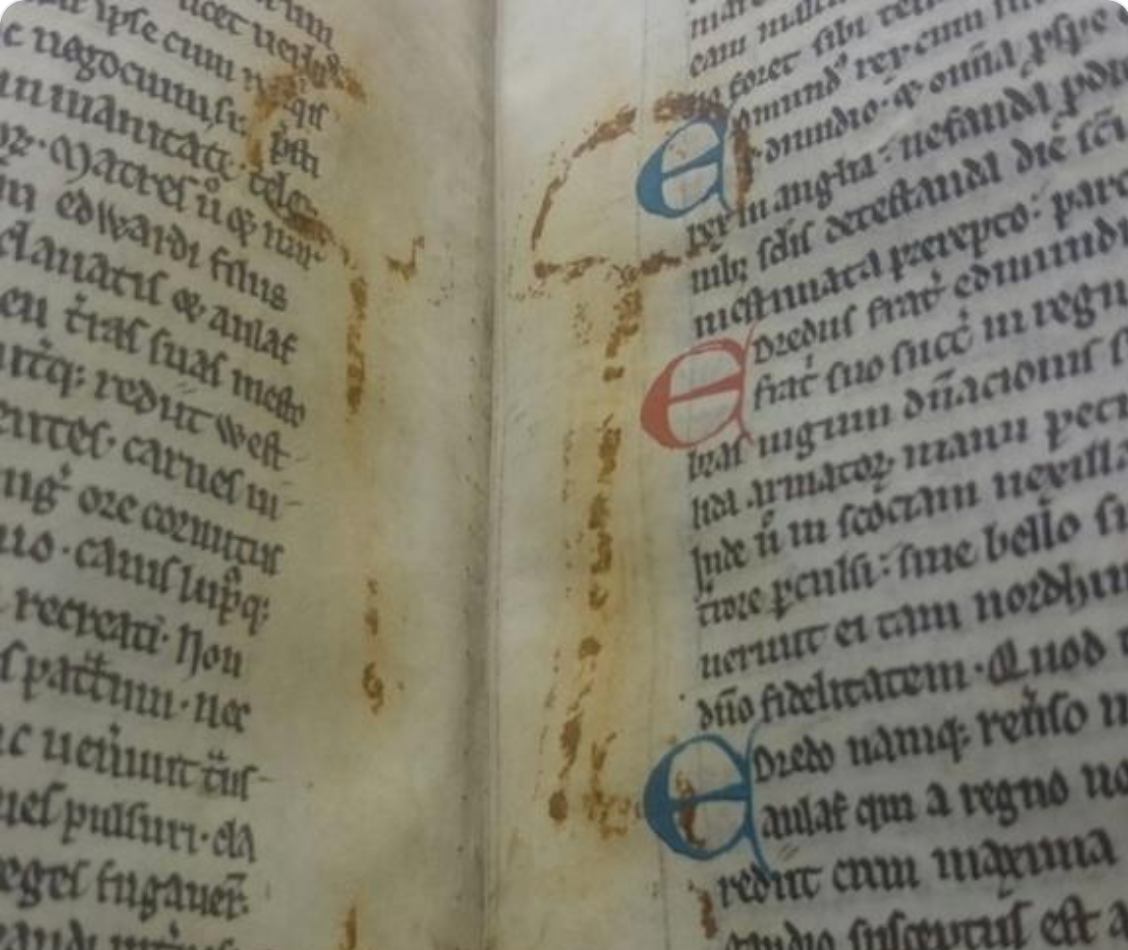

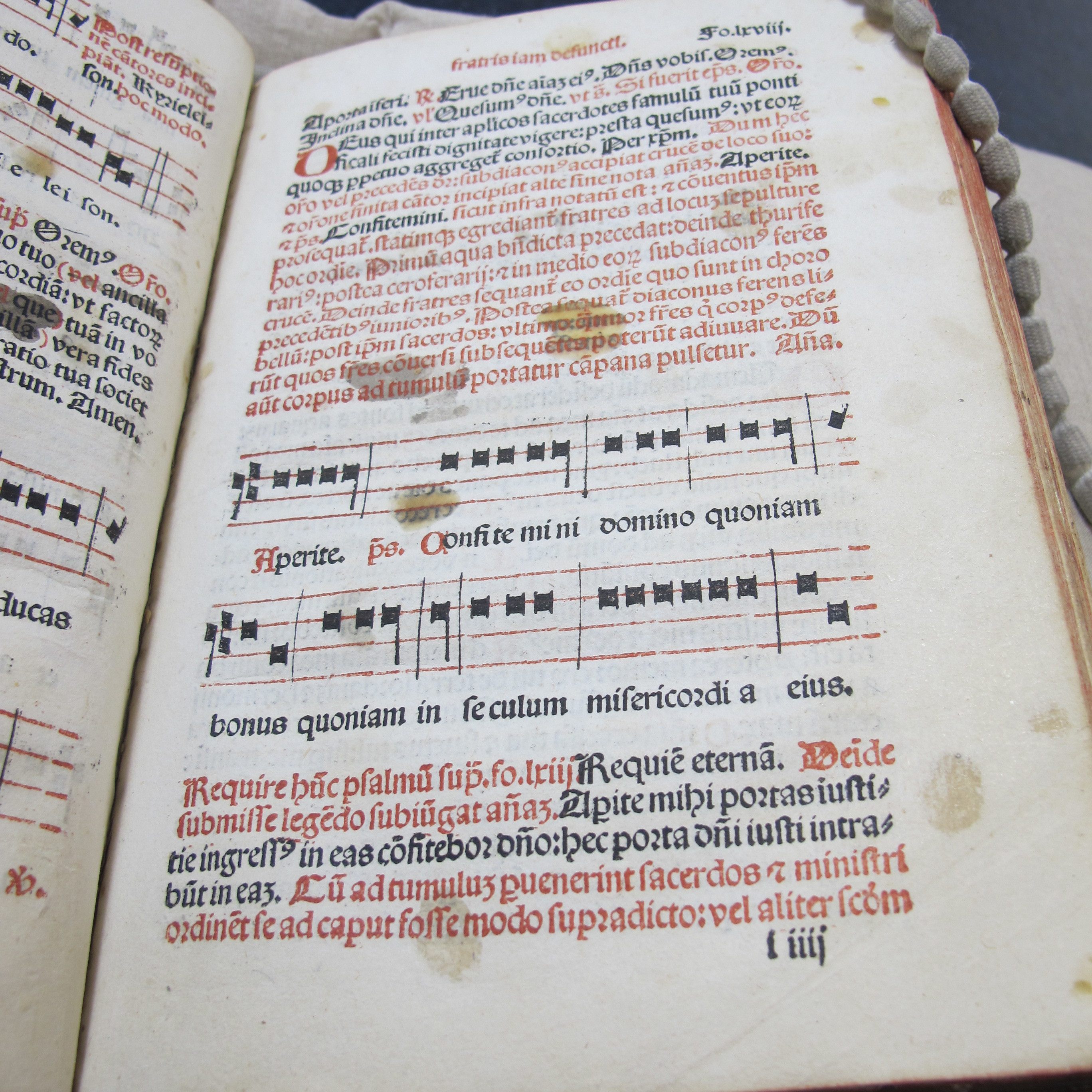

It’s not the first time that Dourish or her colleagues have found foreign objects inside their rare books. Over the years, they’ve encountered flower petals, unexpected annotations, bits of medieval manuscripts within actual book bindings, and even an unknown poem by the Dutch scholar Erasmus. One particularly notable example was a key found by Dourish’s colleague in a medieval manuscript, which left a rusty impression even after its removal. Fortunately, in the case of the cookie or bun, all that remains is “[a] slightly greasy mark” that doesn’t affect the text. “My colleague in our in-house conservation team,” writes Dourish, “took the volume away, gave it a thorough clean, and disposed of the offending object.”

And so the book is back on the shelf, snack-less, waiting to be picked up again—hopefully by someone with a little more respect for the written word.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook