The Secret History of Female and Nonbinary Occultists

A new book examines how supernatural beliefs have often offered a voice, visibility, and vulnerabilities.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

On Thursday, April 18, 1985, Nancy Reagan sat down for tea with an unusual friend. In a quiet corner of the White House, the pair discussed the previous night’s dinner, and how the secretary of state tried to dance with a young starlet. Then they got down to business—the president’s schedule. Would this weekend trip to Camp David be a good one? Should they avoid, say, horses? Nancy took careful notes: when to go outside, when to be careful, what days were “very bad.”

That friend was Joan Quiggly, a psychic medium. In his memoir, For The Record, Don Regan complained how “virtually every major move and decision the Reagans made during my time as White House Chief of Staff was cleared in advance with this woman in San Francisco who drew up horoscopes to make certain that the planets were in a favorable alignment for the enterprise.”

Quiggly was not the first medium to hold sway over American politics. In the 1920s, astrologer Madame Marcia advised first ladies Edith Wilson and Florence Harding. Mary Todd Lincoln held séances to talk to her dead son, Willie, in the White House’s Red Room. In their new book, Toil and Trouble: A Women’s History of the Occult, Lisa Kröger and Melanie Anderson trace the women and nonbinary people who have shaped the occult—and used it to gain personal and political power.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Kröger and Anderson about the social power of occult movements, Benjamin Franklin’s very talkative ghost, and patriarchy in the occult today.

In the United States, how were women able to gain power through occult movements?

Lisa Kröger: I think it was in Spiritualism in the 19th century, that was when we really saw a lot of women taking control of their own voices and their own ideas. But in a safe way. In that time period, “good respectable women” were supposed to stay at home. A good woman was not supposed to be a loud woman. She was not supposed to share her ideas on anything, but especially on religion and politics.

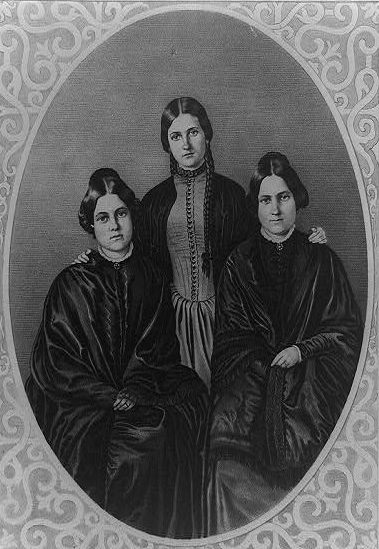

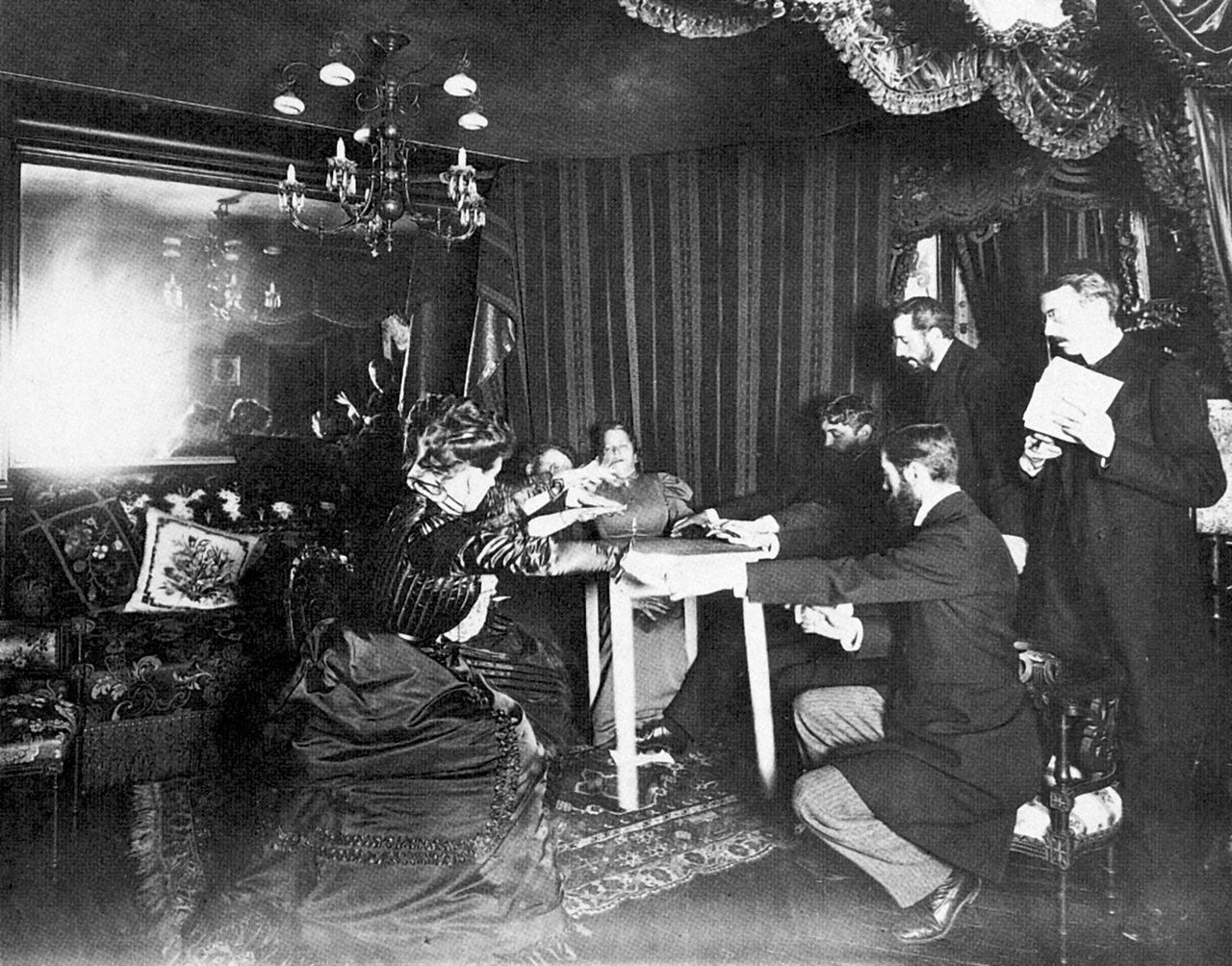

After the Fox Sisters [three teenage sisters who pioneered talking to the dead] entered Spiritualism, we saw quite a few women using the home to their advantage. They could invite or be invited into the parlor of other people’s homes to hold séances. So they’re still working in “the women’s realm,” and under the cloak of Christianity. They would say, “Oh, you know, your brother who passed away during the Civil War? He’s here. He’s with God. He’s with Jesus. He’s in heaven. And he also says, ‘You should free the slaves.’” They were able to say, especially as mediums during the Spiritualist period, that these are not our ideas, “I’m just the conduit.”

I think that’s why a lot of times they channeled Abraham Lincoln or Benjamin Franklin—people who were respected. Then female mediums could put out their own ideas that had to do with societal change or politics or religion without having them dismissed.

Melanie Anderson: When you learn a bit about the history of Spiritualism, it was there alongside these social reform movements the whole time. I feel like sometimes in history, we kind of separate the Spiritualist movement from the political things that were going on at the time, such as abolition and women’s suffrage. But one of the critical voices we use, Ann Braude, makes a compelling argument that Spiritualism did have ties to these political movements.

Why do you think women, historically, have been drawn to the occult?

LK: I think it’s because we have been shut out from places of power. This is why we focused on specifically the history of the United States. You know, we’ve never had a woman president, so we don’t have the track record of political power. I think women then are attracted to the occult—and not only women, but anyone who is not part of that patriarchal hierarchy, such as members of the LGBTQ community, trans women, women of color—when somebody says, “Hey, here is a spiritual belief system that you can not only be a part of, but we’re going to celebrate you and we’re going to let you take leadership roles.”

We talk about this idea of a “witch” and how it became an accusation and moved to something of power. The word today usually evokes power. I think that is very attractive for a group of people who have been told that they’re powerless.

MA: I think it’s also the flip side of women having been connected to negative aspects of witchcraft early on. So it’s not just looking at “witch” as a powerful thing, but also taking a term that was dangerous and making it a positive thing.

And yet these women and others involved often faced a backlash? Why is the occult still so threatening?

MA: I think it’s because we still have some of these oppressive systems in place.

LK: Our country, for good or for bad, is very much tied up with the Christian belief system and that is, in a lot of ways, an oppressive power. I think it’s threatening for some people to see something, like the occult, that so openly goes up against what we hold up as the standard. Plus, I just think that any way we, as a country, can discredit women, we will. We saw a lot of that with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. If you can’t discredit her on her past record or her beliefs, then they’re going to make up some sort of ridiculous satanic cult ritual she’s a part of. So, unfortunately, it’s a tool that’s used to cut people down when they get close to places of power.

MA: And we still have our historical narratives. Anything associated with the occult is automatically also associated with the devil, even though the occult doesn’t really have anything to do with him. We have these binaries and conflicts baked into our folklore. We may be in 2022, but those things are still here.

Are women and others still using the occult this way today?

LK: I’ll give an example of someone we ended our book with, Alice Sparkly Kat. They’re an astrologer and their book is called Postcolonial Astrology: Reading the Planets Through Capital, Power, and Labor. Sparkly Kat looked at astrology and the history of astrology and thought, “This has really been whitewashed. It’s being looked at through a colonialist structure.” Their work is looking at astrology but taking out, as they put it, the white supremacy of patriarchy. Often we talk about planets like Venus and Mars. Those are the Roman names, the Roman pantheon of gods and goddesses. It’s also a very gendered idea of what makes each planet, right? If I were to ask you, “What gender is Venus?” most people would probably say “Female.” That is shifting.

These people who are participating in the occult are not only usually rebelling against patriarchal structures, but are attempting to take everything that we have and look at it through completely a different lens.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook