In a Special Room in an Ohio Library, Toni Morrison’s Legacy Lives On

The Nobel Prize–winning novelist never lost touch with her hometown.

In fall 1993, the city of Lorain, Ohio, was in a frenzy. Toni Morrison had just won the Nobel Prize in Literature, and her hometown couldn’t decide how to celebrate. Officials and citizens held countless meetings and discussions, speaking over each other in excitement. One proposed to rename Broadway Avenue after her. Others wanted to put her name on a school or the local library. “When Toni heard about this, she contacted us,” says Cheri Campbell, the adult services librarian at the main branch of Lorain Public Library. “She said ‘I want a reading room where people can sit and read and just think.’ And that’s what we gave her.”

Morrison, who was born in Lorain in 1931 and died on August 6, 2019, at 88, got her first job at the public library. She worked as a part-time shelver, returning books to their rightful places, until the librarians noticed that Morrison spent more time reading than shelving, Campbell says. Morrison was let go from that position, but soon rehired in the library’s administrative office. Though Morrison spent many years of her life on the East Coast—either at her offices at Princeton University or in her converted boathouse on the Hudson River—she maintained ties with Lorain and its library.

The library officially opened the Toni Morrison Reading Room on January 22, 1995. The writer of Beloved and The Bluest Eye came to the ribbon-cutting ceremony, along with members of her family and poet Sonia Sanchez. Morrison had not prepared remarks, but Sanchez read an original poem for the occasion that moved the author to words. “I remember working at the library, making a little change,” Morrison said, according to the Lorain Public Library’s site. “I spent long, long hours reading there, so I wanted one place available in the neighborhood with a quiet room and comfortable chairs.”

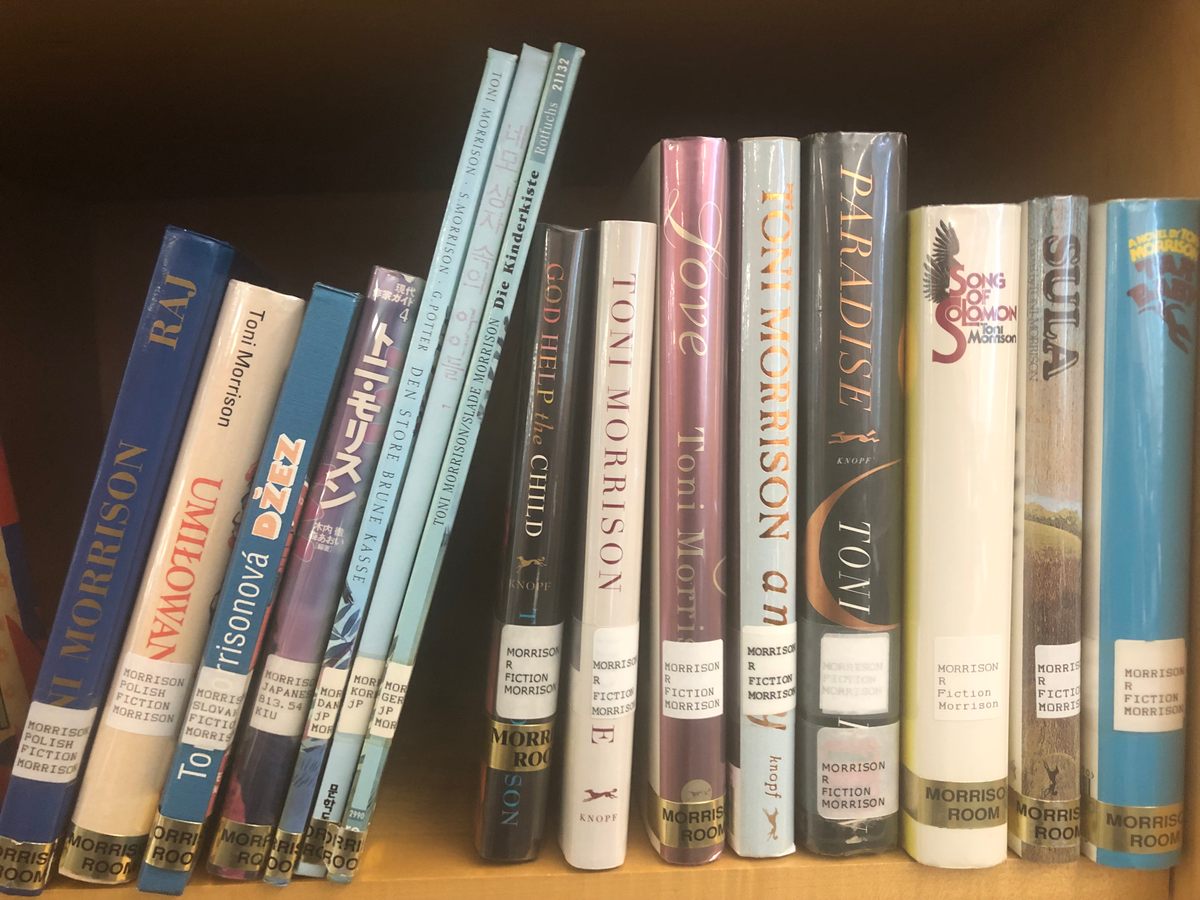

In the years after the dedication, books and memorabilia trickled into the library from Morrison’s office in Princeton, eventually taking the form of a small but formidable altar. Morrison sent copies of her books that had been translated into many different languages, including Japanese, Polish, and Slovakian, as well as pieces of art she thought could hang on the walls. The Lorain librarians assiduously saved nearly every clipping of stories about Morrison in local and national papers and stowed them in a dedicated file. While Morrison donated the bulk of her personal papers, including notes, corrected proofs, and early manuscripts, to Princeton, the Lorain Public Library had, over the years, built up its own record of how dearly the author was cherished in Ohio and the world.

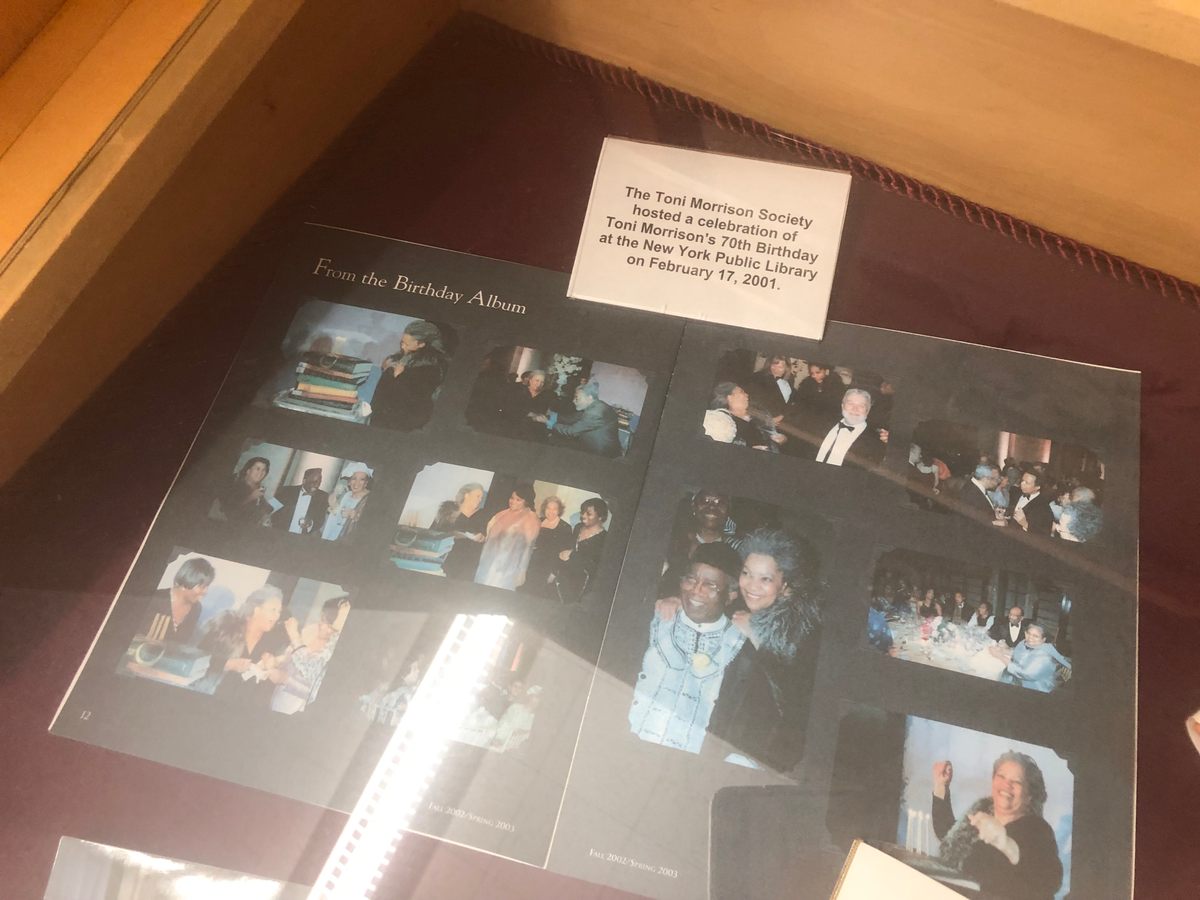

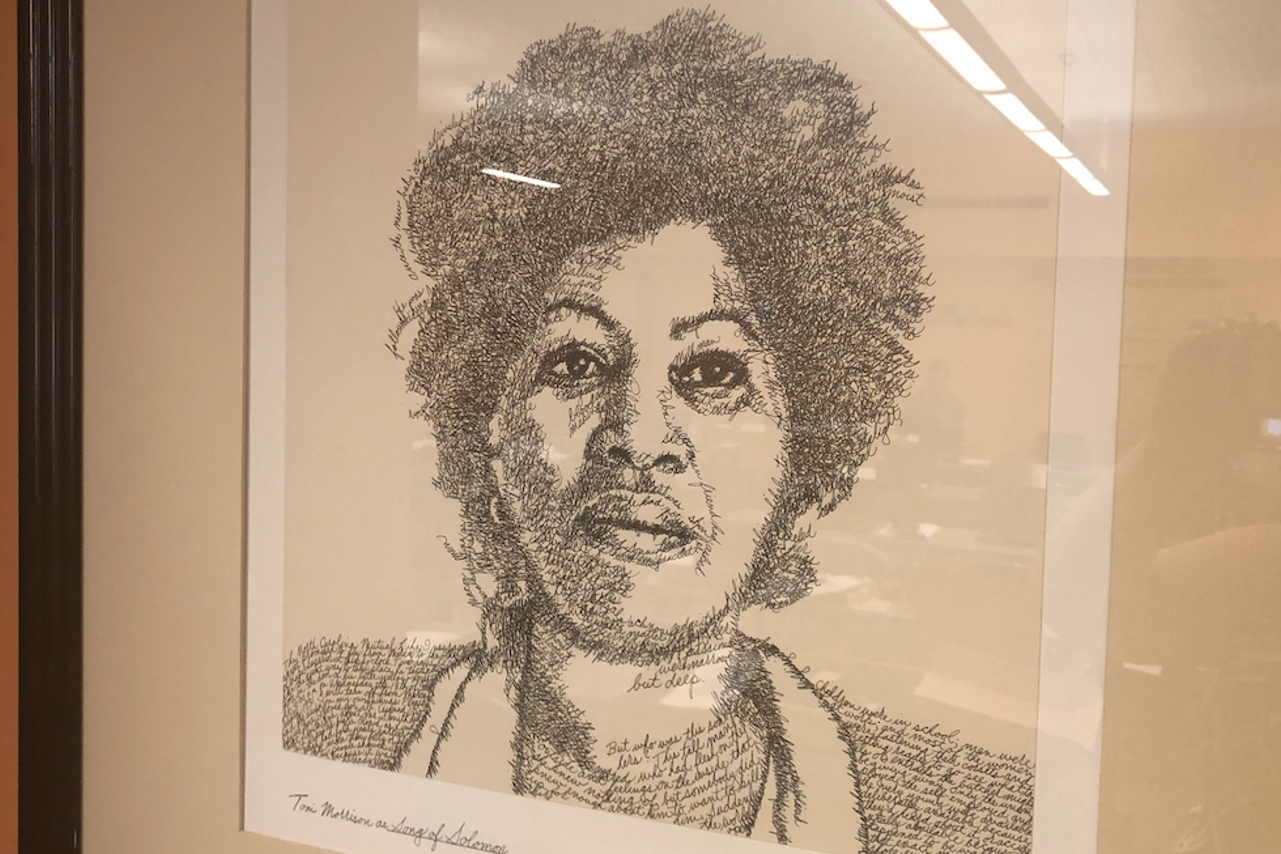

The walls of the Toni Morrison Reading Room are covered in this gratitude. Morrison’s face smiles out from covers on Time and Newsweek. Letters she wrote are kept safe in picture frames, around an enormous painted quilt square depicting Morrison at work. Her friends and family appear in a picture album of the writer’s 70th birthday at the New York Public Library. And at the heart of the room is an original portrait of Morrison by Ohio artist John Sokol. From a distance, the portrait looks jagged, almost like a dot matrix. But up close, one can see that Morrison’s face is rendered not in lines but in letters, specifically the opening lines of Song of Solomon.

The glass wall that frames Morrison’s room is engraved with a portion of her Nobel acceptance speech: “I will leave this hall with a new and much more delightful haunting than the one I felt upon entering: that is the company of the laureates yet to come. Those who, even as I speak, are mining, sifting and polishing languages for illuminations none of us has dreamed of.”

While the Lorain Public Library’s first duty is to serve the residents of the small city less than an hour west of Cleveland, it has also become a meaningful destination for Morrison devotees. “We get people from out of town, people who are scholars. Hilton Als came by,” Campbell says. “Some people even make a pilgrimage from out of state, just to visit us.” When out-of-towners come, quite frequently, Campbell is asked where Morrison used to live. Only one of Morrison’s old residences in the area is still standing—2245 Elyria Avenue—the house she was born in. So Campbell directs people to the Lorain Historical Society instead, which used to hold the branch of the library where Morrison worked. “Lots of times we just stand there and have a conversation about Toni,” she says. “It’s always very reverent.”

Elsewhere in Lorain, the city has begun to mourn their hometown hero. The city council will soon declare February 18 “Toni Morrison Day” in Lorain County. In Cleveland Heights, the Cedar Lee Theater is screening Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, a documentary released earlier in 2019. And the library will host an evening remembering Morrison on August 14, in the reading room, of course. Attendees are invited to read Morrison’s work or share memories of her long, rich life.

Since the author’s death was announced, Campbell says the library has been doing its best to stay on top of the mountain of requests from media, fans, and locals—just another testament to Morrison’s towering impact and legacy. “We knew how much the world loves her, but it’s been kind of overwhelming,” she says. “I guess we just kind of thought she would go on forever.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook