The 19th-Century Book of Horrors That Scared German Kids Into Behaving

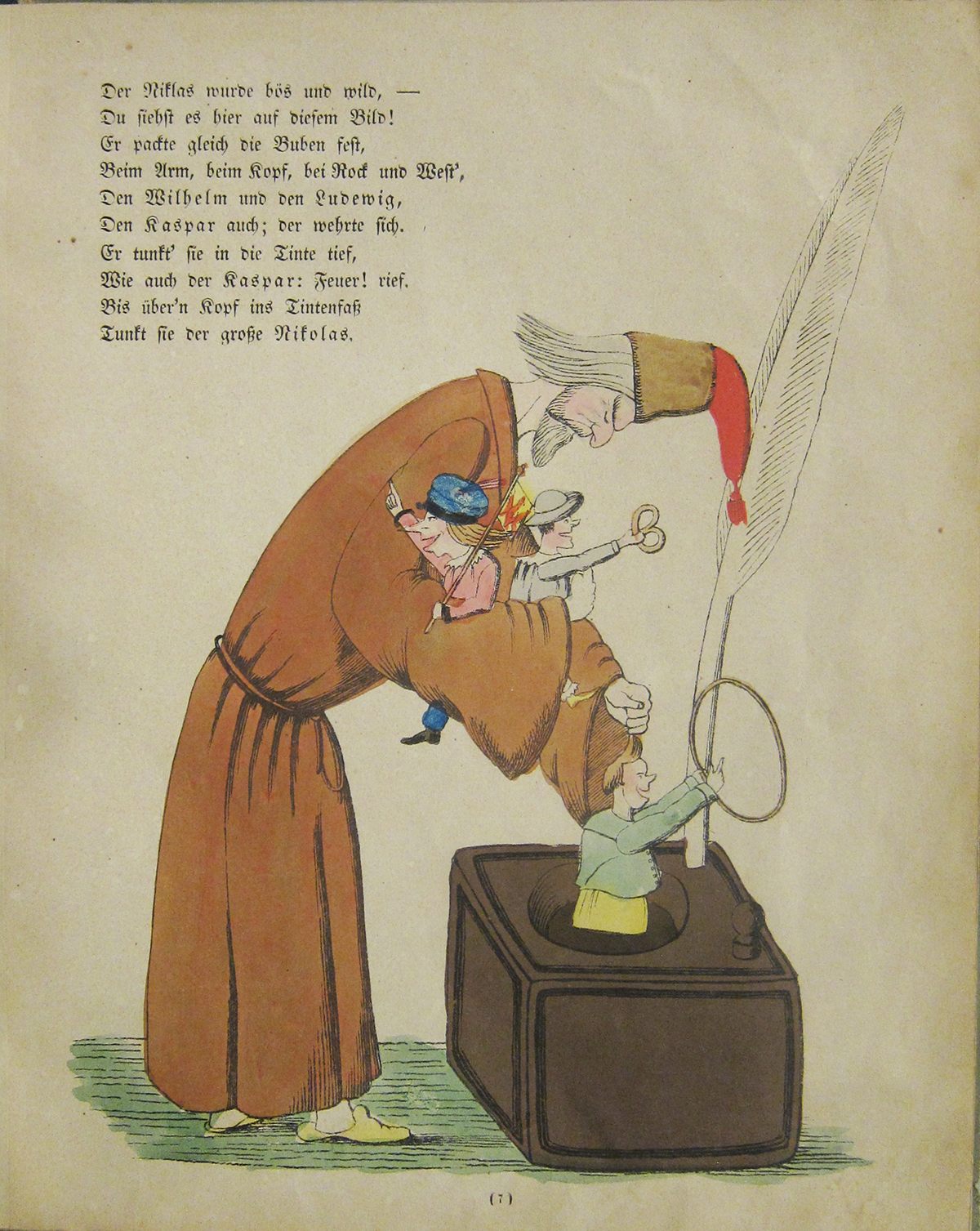

Original illustrations from the book that inspired Edward Scissorhands.

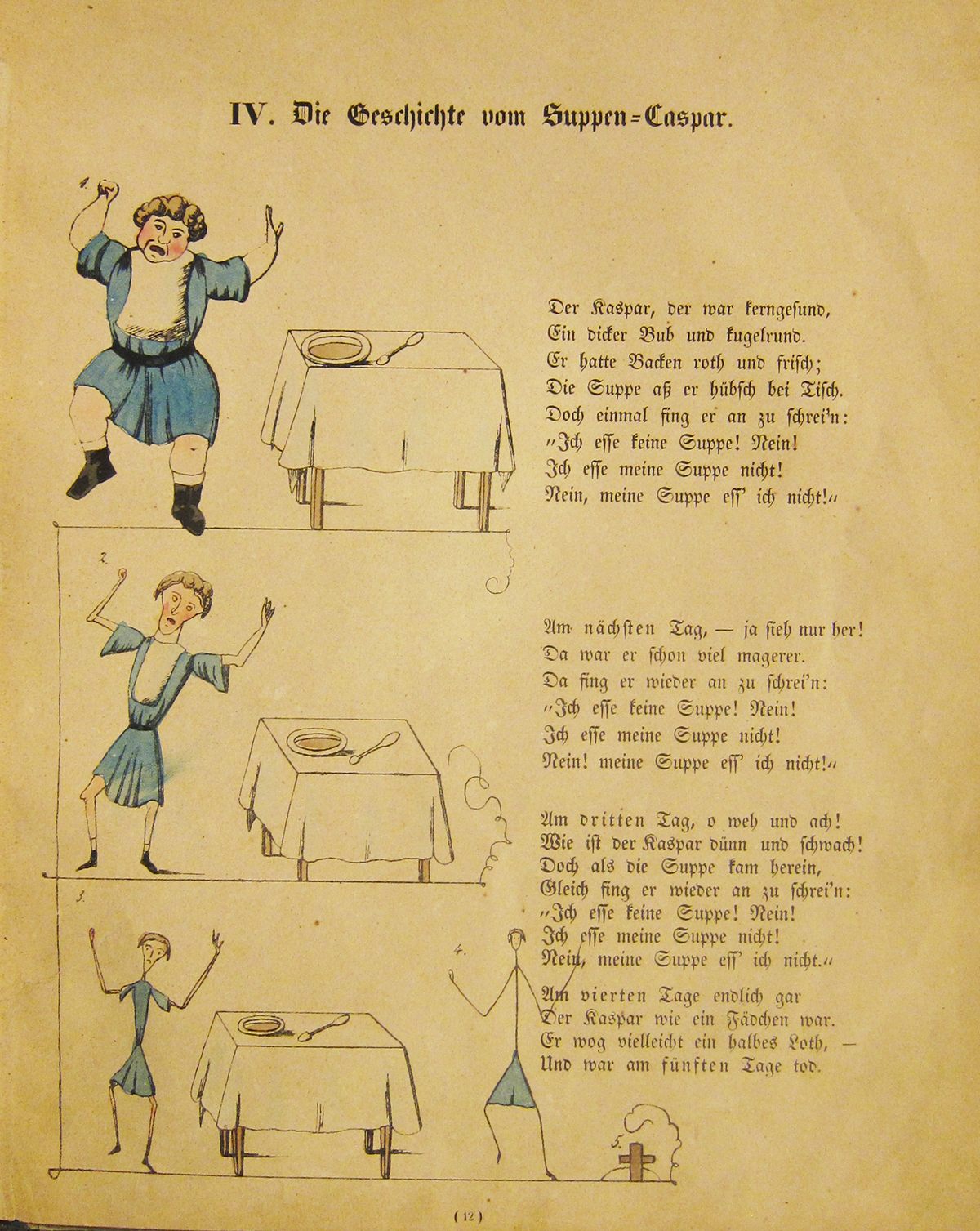

In the original edition of Heinrich Hoffman’s 1845 German children’s book, the most famous character—Struwwelpeter, or “Shockheaded Peter,” whose name later became the book’s title—appeared last. In six short, illustrated stories, Hoffman, a physician from Frankfurt, told grisly moral tales: of a boy who wasted away after refusing his soup, another who lay writhing in pain after a mistreated dog exacted revenge, and yet another who had his thumb cut off after he sucked on it one too many times. Struwwelpeter’s sin was that he never cut his nails, bathed, or combed his hair; his punishment was distinct and cruel—he was unloved.

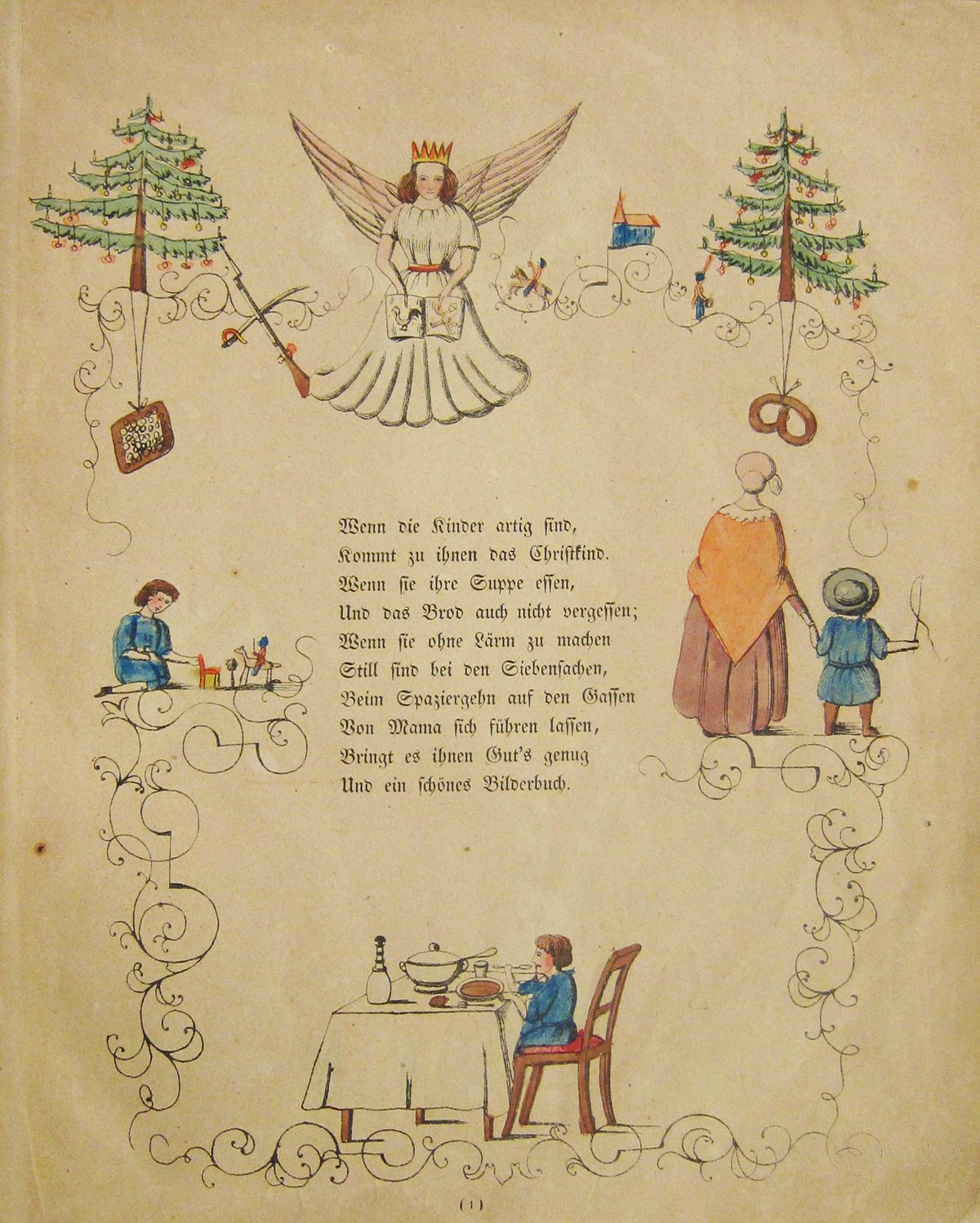

Before it was called Struwwelpeter, Hoffman originally and less compellingly named the book Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder mit 15 schon kolorirten Tafeln fur Kindervon 3–6 Jahren (“Funny stories and droll pictures with 15 color plate, for children ages 3–6”). The New York Public Library’s rare books collection holds one of the original copies from 1845, and the illustrations—Hoffman’s hand-colored originals—from that edition are reproduced here. When the library purchased this copy in 1933, it was just one of four known extant copies of the first run.

The book itself is a slim volume—just 15 pages, each printed only on one side. By Hoffman’s account, he put it together as a Christmas present for his three-year-old son, when no other children’s book would do. (There’s some evidence, as scholar Walter Sauer found, that the book’s generation was less spontaneous and that Hoffman, a doctor, had tried out the stories on his young patients over time.) Hoffman’s book club friends, who had some power in German publishing at the time, encouraged him to release it to the wider public.

The original run was at least 1,500 copies, possibly as many as 3,000, as Hoffman reported in a letter to a friend, and sold out within about two years, prompting a second edition. Starting with that edition, revisions were made to the original drawings. Later versions further elaborated the illustrations, moved Struwwelpeter to the front of the book, and added more stories.

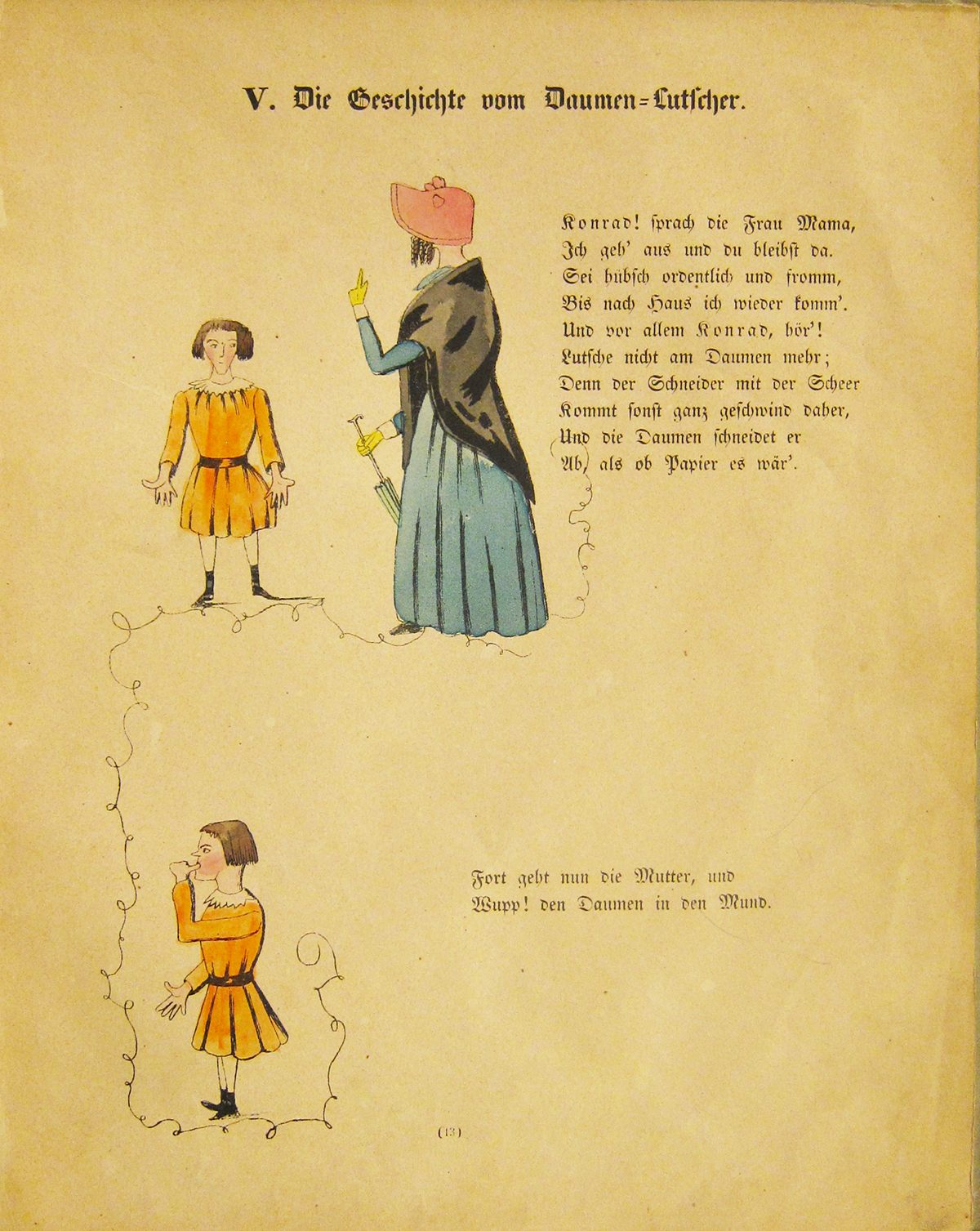

The book proved enduringly popular. By 1848 it was already in its sixth edition and had sold more than 20,000 copies. One of the most famous stories is “The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb,” a boy named Konrad who was warned not to suck his thumb, lest Scissorman come and cut it off. But he can’t resist. He puts his thumb into his mouth and, lo and behold, the terrifying Scissorman appears and snips off the offending digit. This morbid creature quickly entered the canon, and appeared later in diverse texts such as W.H. Auden’s poetry and Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands.

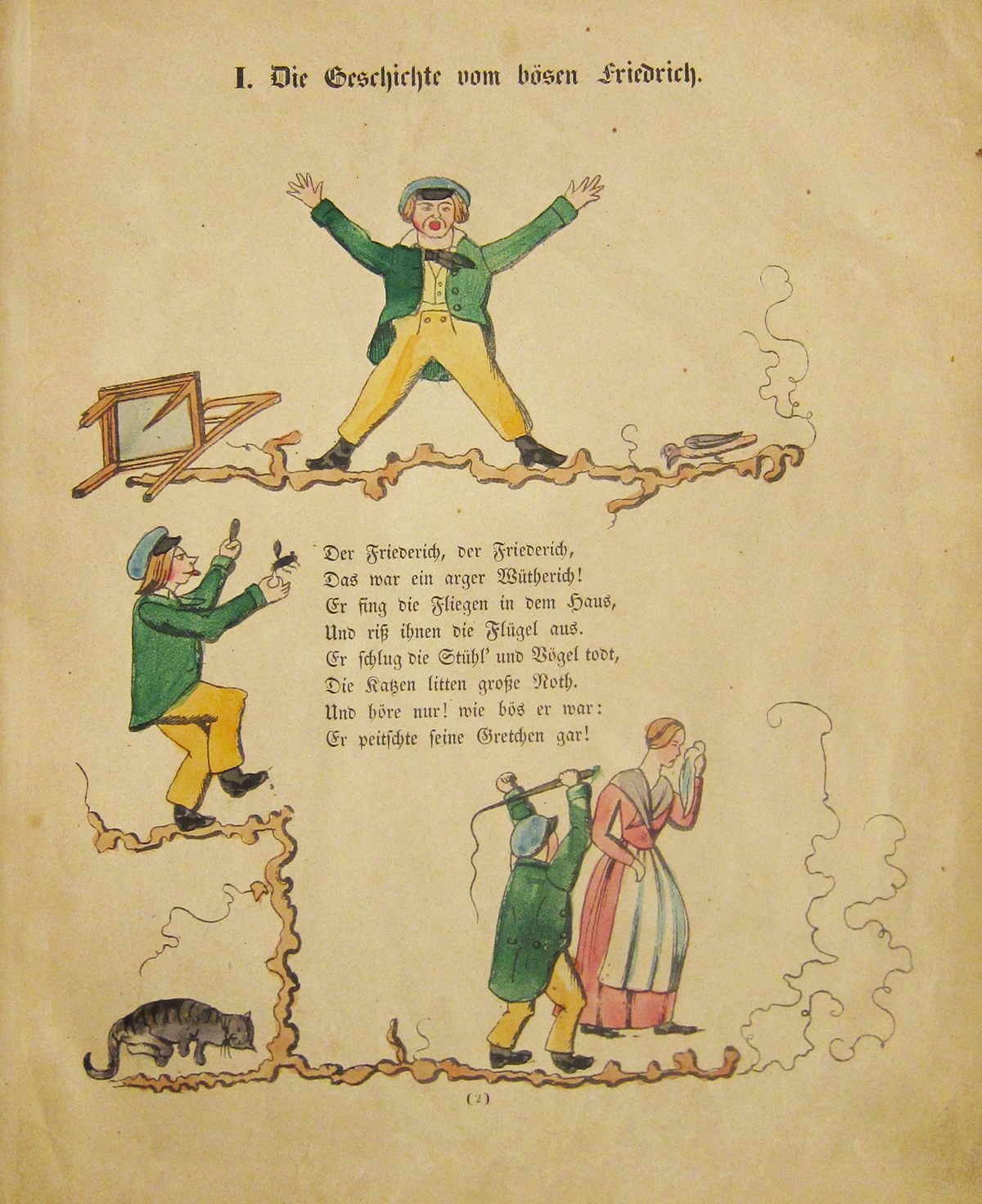

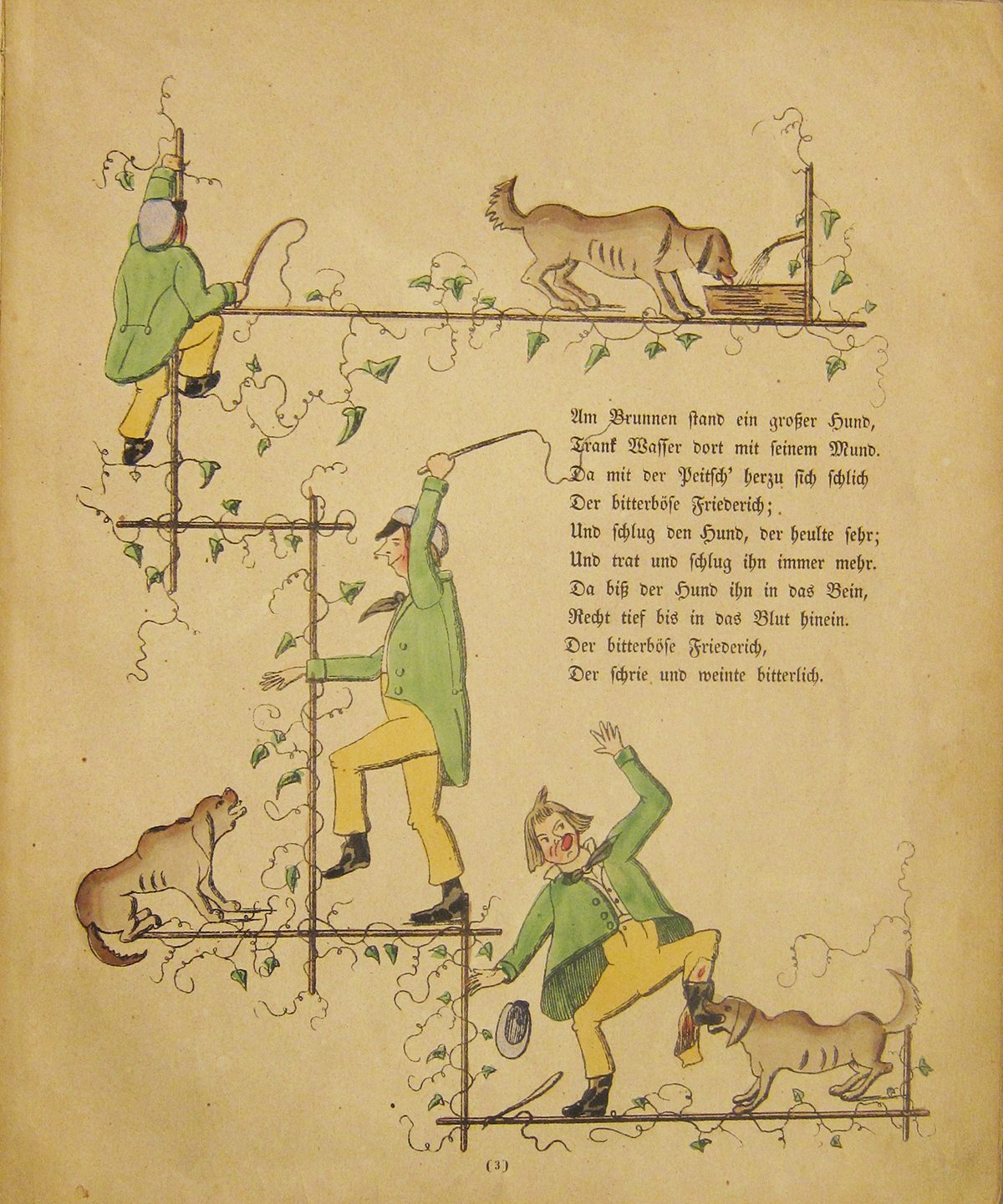

Hoffman spared none of his fictional children. When they misbehaved, they were punished. Cruel Frederick, for instance, was nasty to all creatures, pulling wings off of flies, killing birds, and throwing kittens down the stairs.

But when Frederick beat his dog without mercy, the dog turned on him.

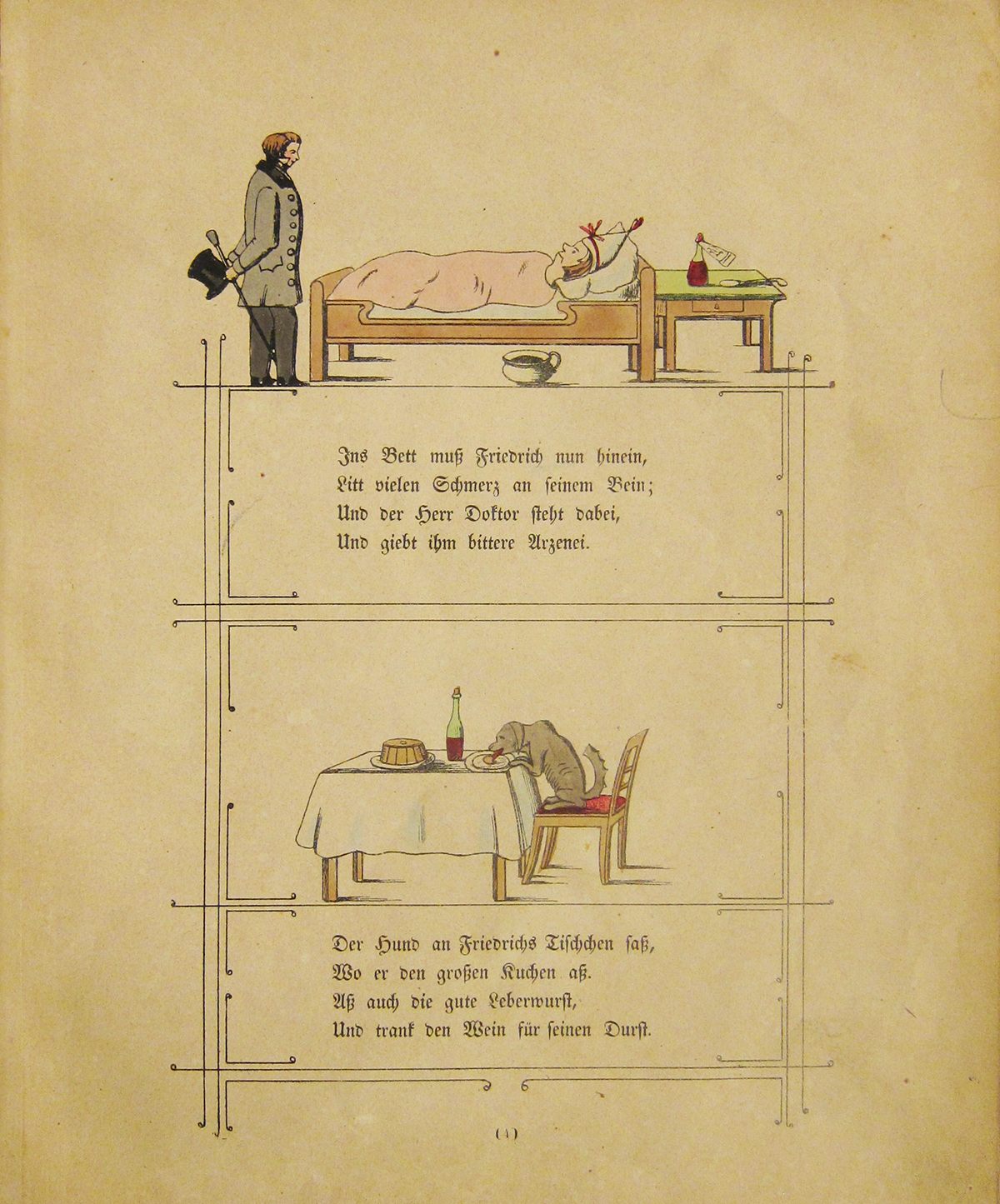

Frederick ends up in the bed, wounded and sick, and the dog is never punished. He gets to eat the boy’s dinner (at the table, no less).

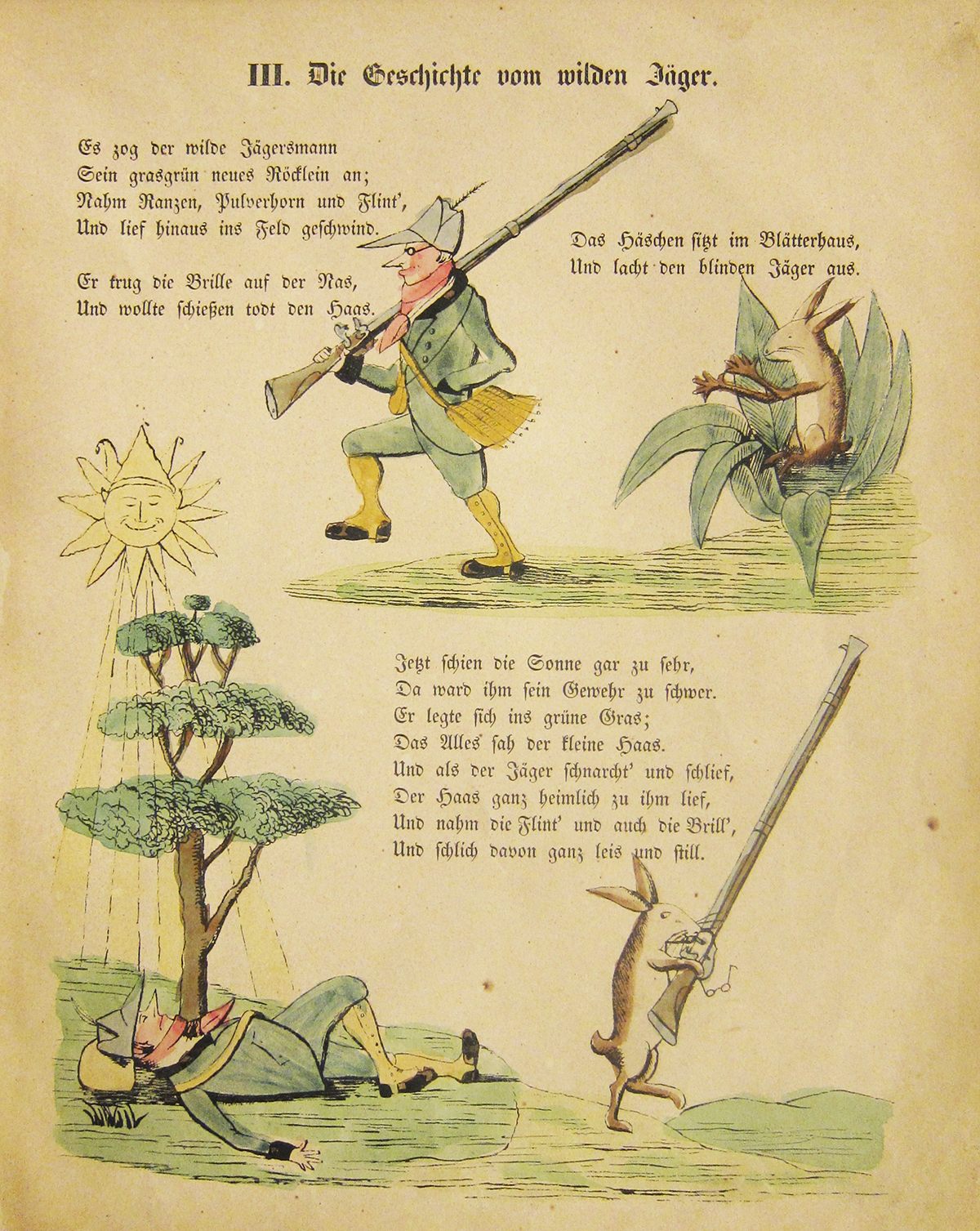

Most of the original stories featured naughty children, but one had a hare as a protagonist. A hunter foolishly falls asleep in the field.

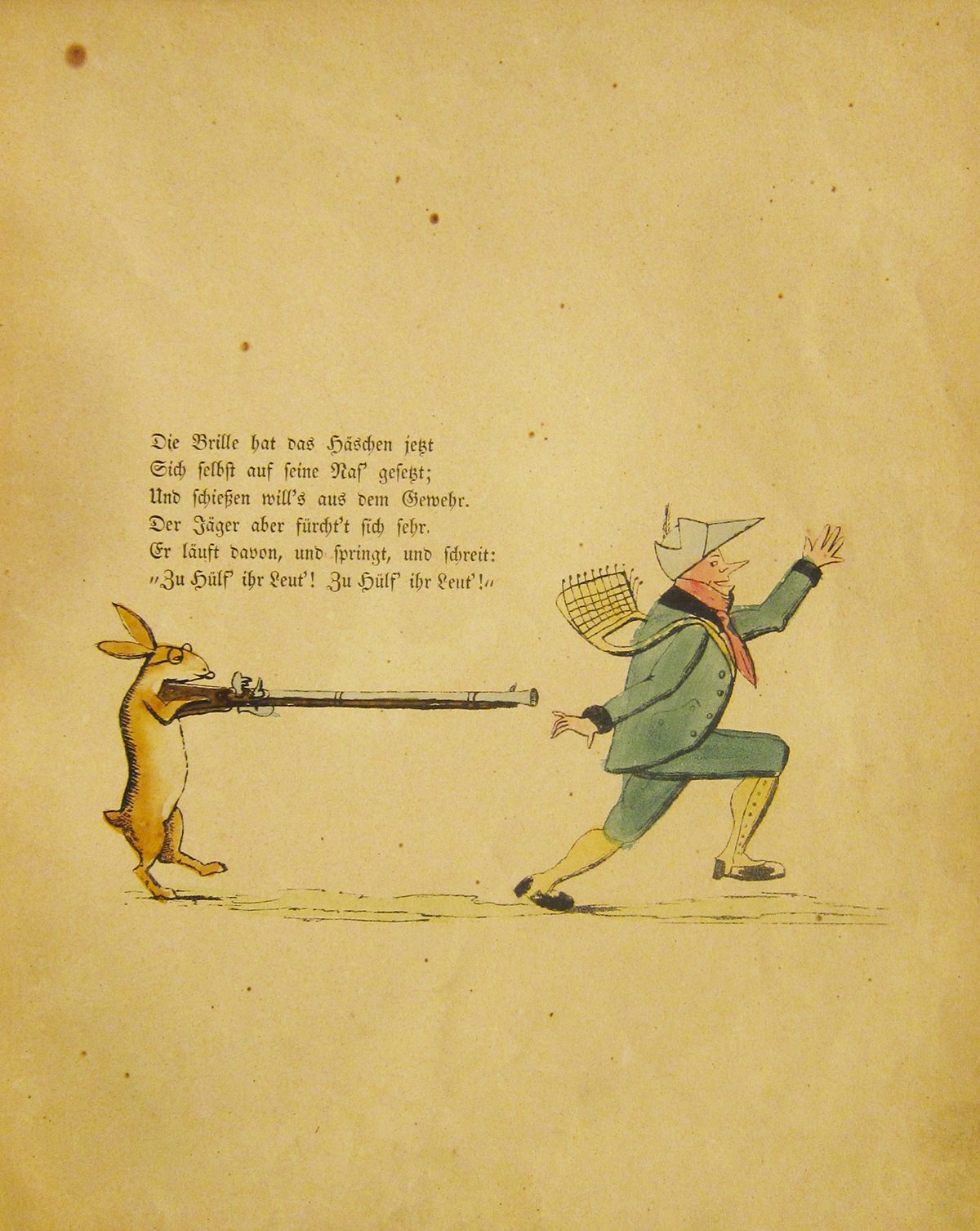

The hare, his prey, steals his gun and, like Bugs Bunny getting the best of Elmer Fudd, turns it back on the hunter. This doesn’t end well for anyone, as the hare’s own offspring is burned by hot coffee in the ensuing chaos.

Most of the stories have a timeless quality. There will always be children who suck their thumbs, are mean to animals, or refuse to eat supper. The story of the inky boys veers into not-so-timeless territory. It’s a story of three white boys who harass a black boy for the color of his skin.

The language used to describe the black boy wouldn’t be published today, and the illustration, which shows the white boys clothed and the black boy in a loincloth, also betrays the racist tropes of its time. The boys are indeed punished for making fun of the boy for the color of his skin—a lesson that wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary storybook—but, as part of their punishment, they’re dipped in black ink. The lesson might be that they should learn to accept difference—but being black is still stigmatized.

As the book was reworked over the years, the simple illustrations became more and more elaborate and packed with detail. Soon the hand-coloring gave way to color-printing with wooden blocks. But the originals remain enchanting, disturbing, and haunting on their own. Even today Struwwelpeter and Scissorman are hard to forget. One can only imagine the effect they had on German children in the mid-19th century.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook