The Incredible Story of the World’s First Papier-Mâché Gorilla

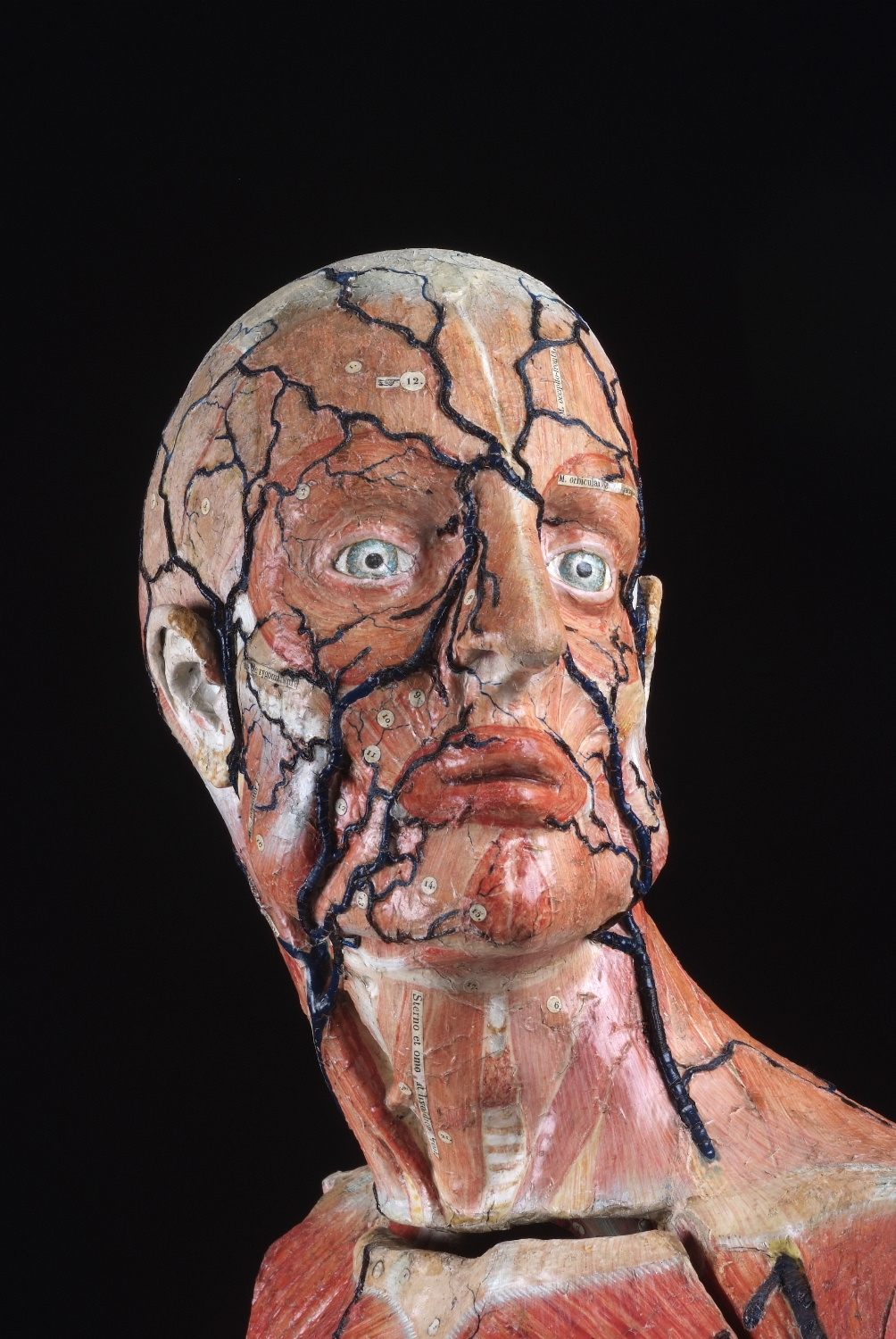

Dr. Louis Auzoux’s greatest creation was made of bone and scrap paper.

Ask Bart Grob, of the Museum Boerhaave in Leiden, Netherlands, about what appears to be a skinless ape in his museum’s collection, and he’ll tell you quite a tale. “As a curator, if you are lucky, you come across this once in a lifetime.” Few people speak so rapturously about papier-mâché gorillas.

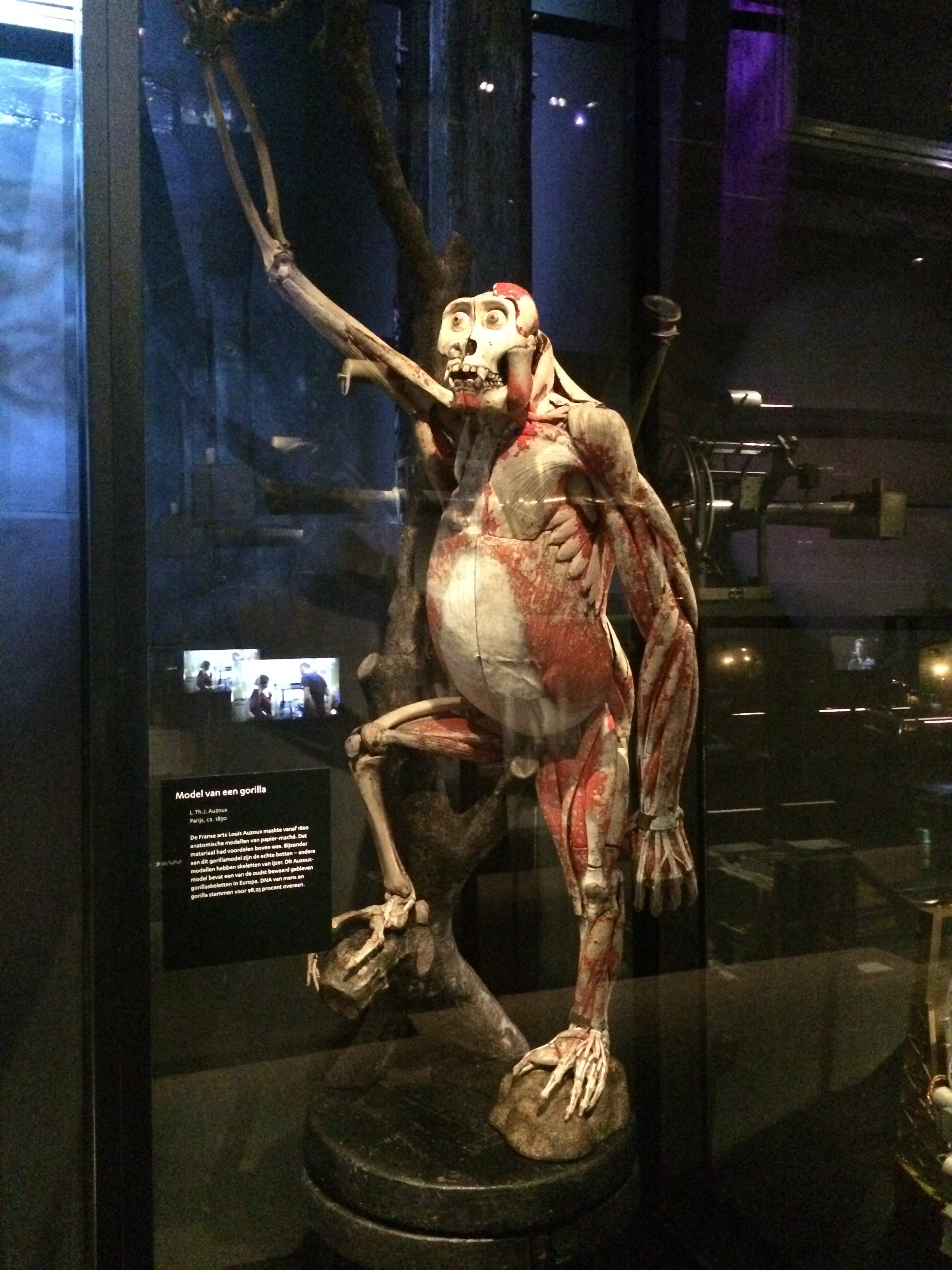

The gruesome specimen in question is one of thousands of anatomical models produced by the Victorian-era biology factory of Dr. Louis Auzoux. What makes the Auzoux ape in the Boerhaave collection unique is the bones. That, and it was once used as a coat rack.

To understand the significance of Grob’s find, it’s necessary to appreciate the life’s work of Louis Auzoux. A surgeon by training, Auzoux was a pioneer in the field of anatomical models. He worked primarily in papier-mâché, possibly inspired by the art of puppet making. “You find anatomical models from different types of materials. Wood, ceramic, and wax models are very famous. But Auzoux, and his competitor [Francois] Ameline, experimented with papier-mâché beginning around 1820,” says Grob, who oversees what he believes is the largest collection of Auzoux’s work in the world. “Before it dries, you can sculpt [papier-mâché] into any form you want. When it dries, it’s as hard as wood.” Less sticky than wax, more workable than wood, and sturdier than ceramics, Auzoux used the material to create intricate, multi-part biological models.

Over the years, Auzoux was able to streamline and perfect his process, expanding the scope of his models at the same time. He eventually focused on “dissectable” models that could be taken apart and reassembled, piece by piece. As for the exact recipe of Auzoux’s papier-mâché, that remains a mystery to this day, although it was known to contain cork, paper, starch, and clay. “It was a secret recipe. We don’t know for sure what was in it, but it was common,” says Grob.

Auzoux’s models were a hit with medical colleges and related institutions. His creations were cheaper and easier to obtain than a corpse, plus they were reusable. By 1827, demand for Auzoux’s work reached the point that he was able to open a full-fledged factory. He constructed wood and metal molds for every individual piece of each model, making his anatomical creations easy to reproduce. “The young boys would make the molds, the younger, stronger men would carry the heavy molds, the women would paint the pieces,” says Grob. Auzoux would also go on to write a textbook, which handily doubled as a catalog of his offerings.

The factory produced models of everything from humans to moths to horses, and eventually, gorillas.

Gorillas were scientifically described for the first time in 1847, and Auzoux began producing papier-mâché gorillas some time in the 1860s. According to Christie’s auction house, in 1863 he received a female gorilla specimen from Emperor Napoleon III. By 1869, Auzoux’s company was selling gorilla models for 3,000 Francs.

By the time Grob made his once-in-a-curator’s-life discovery, he’d been searching for an Auzoux gorilla to add to his collection for years. “We received a phone call from a friend of the museum, a collector. He was walking at the flea market in Paris. There, he saw a gorilla model on sale,” says Grob. Anxious to see it for himself, Grob headed to Paris the next day. “We arrived, and the gorilla was on sale, but not in an antique shop. The owner was an Irish guy who traded in decorations, like tables and crystal hangings. He kept it in his house.” The seller, apparently unaware of what he had, had been using the gorilla model as a coat rack.

Much to Grob’s astonishment, he found that this gorilla wasn’t just another of Auzoux’s mass-produced papier-mâché products. This one incorporated pieces of real bone, including “part of the skull, its teeth,” he says. “We know that there are six other gorilla models still existing today, but this is the only one with bone in it, so we assume that this is the first model.”

After acquiring the model, it needed a great deal of restoration, but it is now on display at the Museum Boerhaave. “This is the Rembrandt of our Auzoux collection,” says Grob.

Auzoux’s factory produced thousands of anatomical models, many of which can now be found in museums across the world, including the National Museum of American History. But there is only one gorilla model made of both bone and papier-mâché. As one of the earliest fully realized anatomical models of a gorilla anywhere, Grob sees its importance as greater than just a rare Auzoux prototype. “It’s almost the birth certificate for King Kong.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook