Death as Entertainment at the Paris Morgue

In the late 19th century, tourists flocked to see bodies and guess how they got there.

In August 1886, when curious Parisians opened up the newspaper Le Journal Illustré and read its cover story on “Enfant de la Rue du Vert-Bois,” a four-year-old girl found dead with a single mysterious bruise on her hand, they knew what to do. One by one, readers of the paper rushed to the Paris Morgue, where they pushed their way into its curtained Exhibition Room. There, behind the glass, sat the body of the girl, posed in a tiny dress.

The sight was haunting. And everyone wanted to witness it for themselves.

By August 5, a few days after the newspaper’s release, the crowd outside the Morgue had grown so massive that it spilled into the street. Traffic stopped. Parisians were so eager to get inside that they frequently broke into skirmishes. Reported a newspaper at the time, “The mob rushes the doors with savage cries; fallen hats are tromped on, parasols and umbrellas are broken, and yesterday, women fell sick, having been half suffocated.”

At that point, over 150,000 people had visited the Morgue to see Enfant de la Rue du Vert-Bois.

Yet such a massive outpouring was not unusual. Although the Enfant de la Rue du Vert-Bois case brought it to new heights, the Paris Morgue frequently received hordes of visitors. In fact, by the end of the 19th century, the Morgue had become one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions.

The Morgue may have existed so that friends and family of the dead could identify anonymous bodies, but few visitors came with any intention of looking for a missing person. They had a single goal: to see the dead up-close. The more gruesome or mysterious a person’s death, the more tourists showed up to see their body.

As USC history professor Vanessa R. Schwartz writes, “The Morgue served as a visual auxiliary to the newspaper, staging the recently dead who had been sensationally detailed by the printed word.” Whenever newspapers reported on an unknown decapitated person or a bloodied trunk on display, tens of thousands of people flocked to the Morgue to see it.

Schwartz cites another example: in 1895, a French daily newspaper reported that the body of an 18-month-old child had been pulled out of the Seine River. The next day, when a three-year-old was found in the river nearby, the paper asked: “Are these two sisters?” In response, locals rushed to the Morgue in hopes of speculating for themselves. The crowds swelled to such a degree that the city dispatched police officers to keep the peace.

In an 1885 story for The Crimson, an American writer described a trip to the Morgue like this:

Men are crowding and elbowing each other; old hags are pointing toward the glass, and croaking to one another; pretty women are gazing with white faces of pity, but with none the less thirsty greediness, upon some fascinating spectacle; little children are being held aloft in strong arms, that they too may see the dreadful thing, and they do see, and they toss their tiny, wavering arms aloft and crow right gleefully.

By the end of the 19th century, the Morgue attracted so many visitors that nearly every Paris guidebook mentioned it. The social commentator Hughes Leroux wrote in 1888, “There are few people having visited Paris who do not know the Morgue.” Even local vendors quickly cashed in on the hype: the sidewalk outside the Morgue often overflowed with people “hawking oranges, cookies, and coconut slices.”

Though other morgues attracted tourists, none rivaled Paris. This was intentional: when the Paris Morgue was rebuilt in 1864, city planners designed it to attract as many visitors as possible in hopes of speeding up the identification of corpses. Not only did the new morgue stand behind the cathedral of Notre-Dame in the heart of the city, but the building was also open from dawn to dusk seven days per week—far more than any other major morgue at the time.

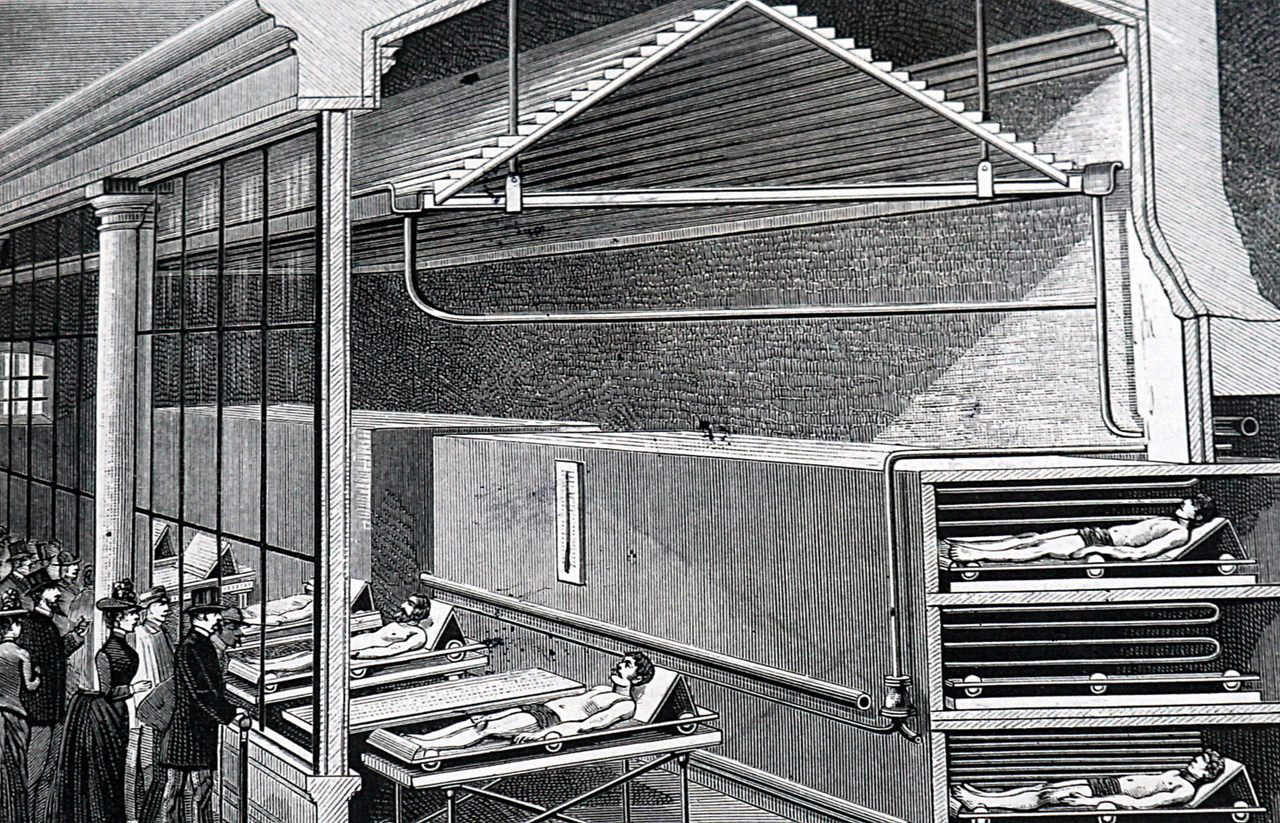

Even the Morgue’s internal design was inviting. Inside the Exhibition Room, which held as many as 50 visitors at a time, two rows of corpses lay on rock slabs behind glass windows. Bookending the windows were a pair of green curtains that commentators in the era likened to those in a retail setting: “Picture a large department store window when the merchandise has been removed on a Saturday night.”

Morgue workers draped the corpses’ clothing on pegs next to the bodies. In the Morgue’s earlier years, cold water dripped onto the bodies from a tap in the ceiling to slow down decomposition; by 1882, that was swapped out for an extensive refrigeration system.

The Morgue’s well-attended displays earned frequent comparisons to the theater. French novelist Émile Zola, for instance, called it a “show that was affordable to all.” On rare occasions when there were no bodies on display, angry crowds complained “that death allowed itself an intermission that day, without thinking of their good pleasure.”

Yet when commentators called the Morgue a theater, they weren’t simply referring to the sight of the bodies. Visitors might find themselves with front-row seats to dramatic criminal investigations, too.

Police often brought suspected murderers to the Morgue to confront their victims, believing that the shock of seeing what they had done would trigger a confession. These “confrontations” were common enough that, in 1888, the Paris Morgue installed electric lights “with the idea of increasing the effect produced upon murderers upon being confronted with their victims. Under the effect of the lights the ‘confrontations’ are expected to be much more effective.”

This tactic actually worked. Paris police records list several instances of suspects who, after initially refusing to cooperate, confessed their crimes upon visiting the Morgue.

In this sense, the Paris Morgue can be seen as a precursor to the modern true-crime films, television shows, and podcasts that have dramatized murder stories. Much like viewers of these programs, morgue tourists could examine the dead, speculate on the nature of their passing, and also, if the timing was right, watch the whole narrative unfold.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook