The Tiny Globe That Puts the World and Heavens in Your Palm

Elizabeth Cushee’s elegant 1745 orb was boundary-pushing at the time.

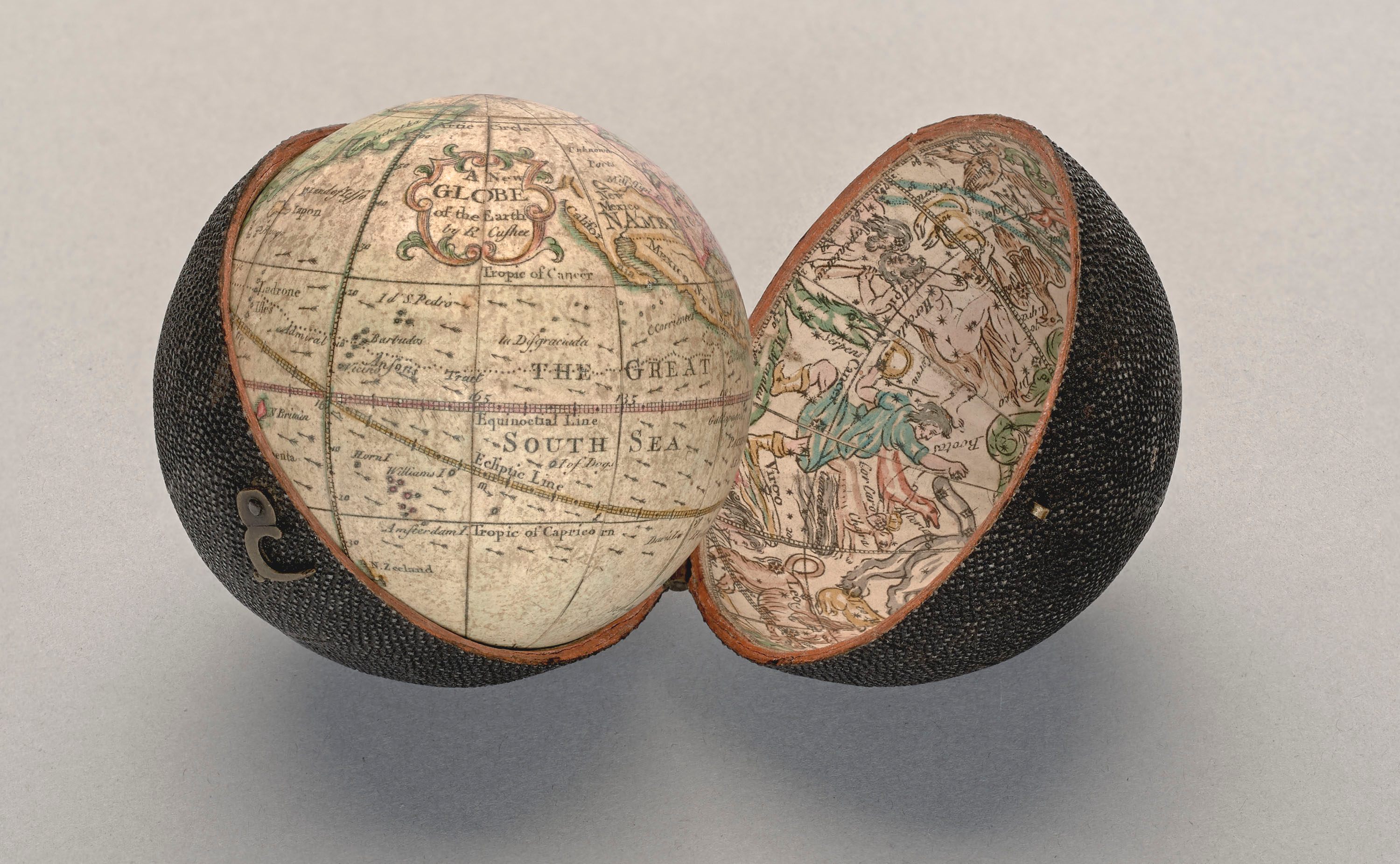

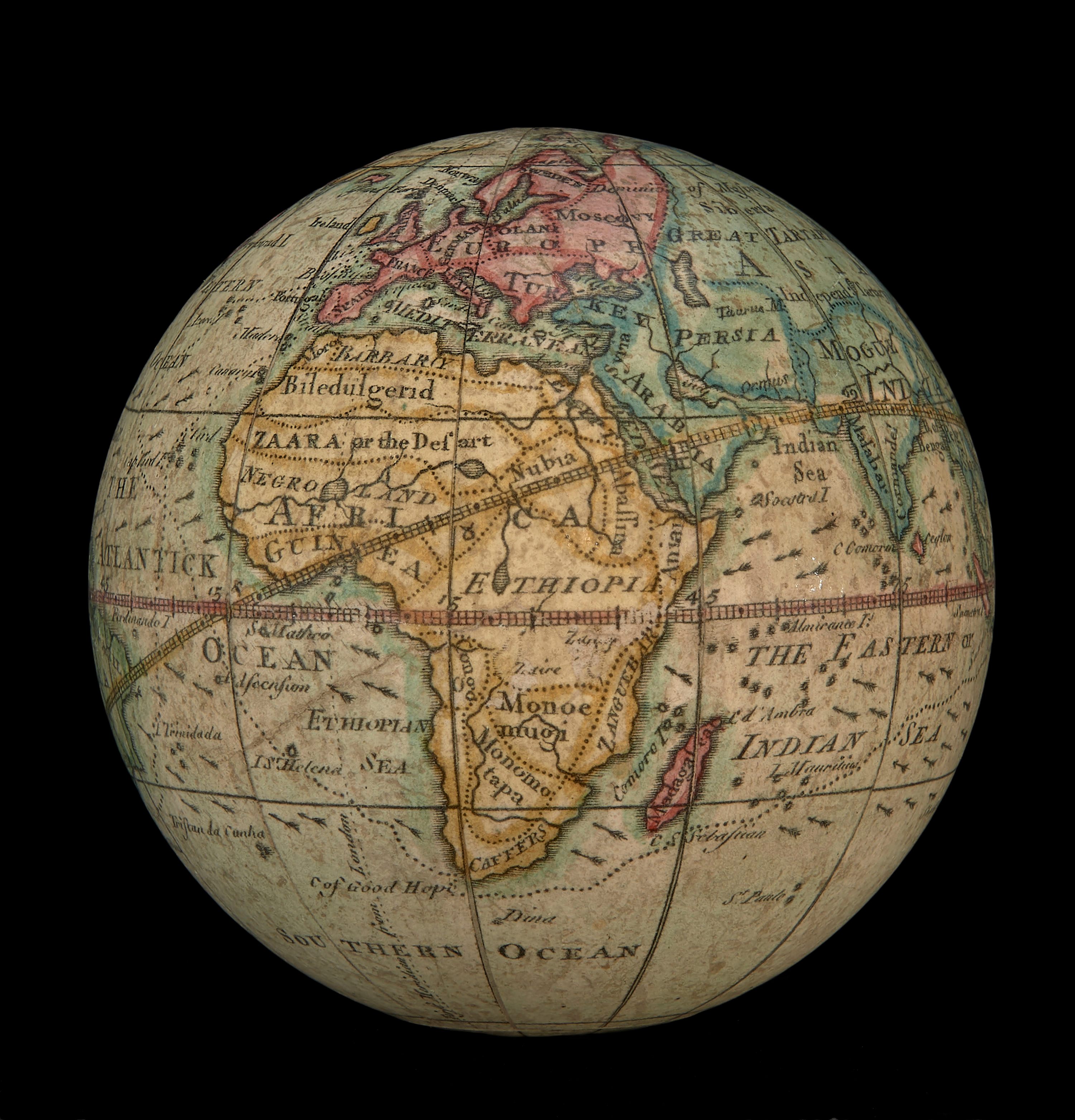

Around 1745, Elizabeth Cushee shrank the entire world onto a wee little globe measuring just three inches across. Fashioned from paper gores curved and pasted onto a hollow wooden orb, the globe weighs no more than a few ounces. It fits snugly inside a fish-skin case, the scaly exterior of which evokes the celestial confetti of the night sky. A smattering of colorful constellations are pasted onto the inside of the case, where they loom over land and sea. Continents and cosmos mingle in a curio the size of a plum.

Pocket globes had been circulating since the 1600s, especially among sailors and students of cartography, write science journalists Betsy Mason and Greg Miller in their recent book, All Over the Map: A Cartographic Odyssey. At the time, cartographic works ran the gamut from erudite and accessible, both in content and price. Lavishly illustrated atlases and star charts were designed for a lay audience, while comprehensive catalogues helped astronomers and navigators get more precise bearings. Cushee’s fell somewhere in between.

Other 17th- and 18th-century Dutch and English pocket globes sold for 6 guilders and 15 shillings, respectively, Miller says—roughly $75 or $100 today. Globes like Cushee’s “weren’t affordable for everyone, but they weren’t only for the super-rich either,” Miller says. “They were the sort of thing a middle-class person might buy to project a certain air of worldliness and sophistication. I can totally see an 18th-century social climber whipping one out at a garden party to impress his friends, or maybe to mansplain the cosmos to a lady.”

Cushee didn’t need to be condescended to. Her edition was an improvement upon one made by her late husband, Richard, a British surveyor, in 1731. Elizabeth updated Richard’s version to be in line with the cartographic knowledge of the time, Mason and Miller explain. She added arrows to mark the path of the trade winds, and attached California to the coast of North America (previously, it had floated as an island). She also mapped the route of George Anson, a Brit who had been cheered as a hero when he had returned home the previous year, following four years of sailing around the world, pestering Spanish ships, and fracturing trade routes.

The Cushees also tweaked the way the constellations were oriented. Most globes and celestial charts of the era depicted the constellations from the perspective of a distant god gazing down at Earth, Miller says. On both Richard and Elizabeth’s versions, Ursa Major, the bear, faces to the right, the way we see it when we look skyward. Some things are a little off—where’s the other half of Australia?—but squeezing all of this detail and information into so small a package was a feat.

While Miller hasn’t been able to dredge up much information about Elizabeth Cushee’s life, “It wasn’t uncommon for women to be involved in the family mapmaking business back then,” he says, “even if they didn’t always get credit for it.” Cushee’s cartographic creativity places her among a smattering of women who have charted the Earth and helped make sense of the heavens—often with little earthly fanfare.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook