Meet the Rottweiler-Sized Prehistoric Otter With Teeth That Could Crunch Bone

Can an apex predator be cuddly?

Otters are cute semiaquatic mammals, whose charming lutrine behavior has launched hundreds, if not thousands, of online videos. They hold paws so they don’t drift apart while sleeping. They crack open shellfish with rocks. Sometimes, they snack like a moviegoer with a tub of popcorn. It’s adorable. Decidedly less adorable, however, is their recently discovered ancestor, Siamogale melilutra. This 110-pound swamp creature was roughly the size of a Rottweiler, and lived in what is now China’s Yunnan Province around six million years ago.

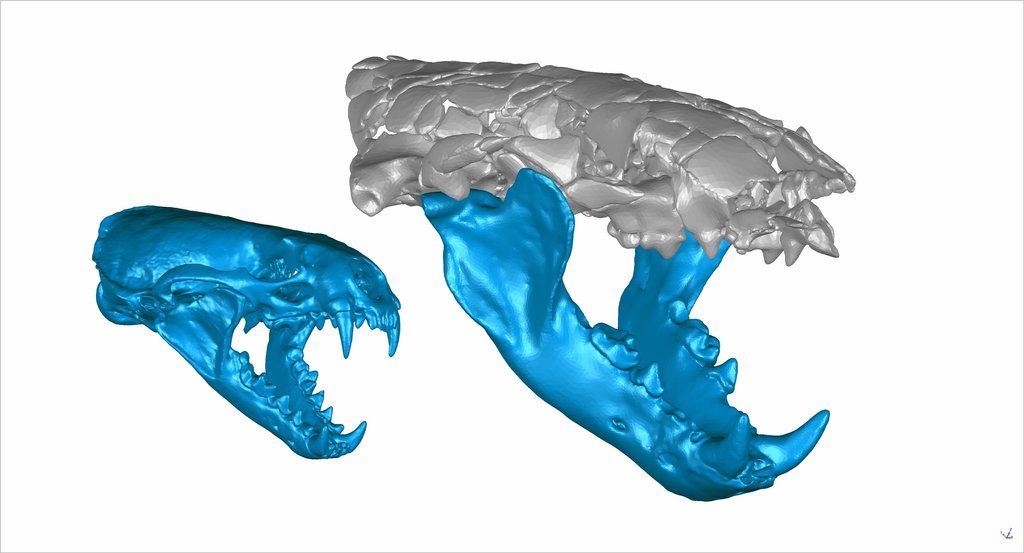

Where modern otters reach for a rock to open a difficult mussel or whelk, S. melilutra had jaws so powerful they could crush even the thickest seashells to smithereens. Scientists published a study today in Scientific Reports to share their work on modeling the prehistoric otter’s bite with computer simulations. “We started our study with the idea that this otter was just a larger version of a sea otter or an African clawless otter in terms of chewing ability, that it would just be able to eat much larger things,” said Z. Jack Tseng, who led the project, in a statement. “That’s not what we found.” They found powerful jaws that could chomp through quite sizeable prey, dead or alive. Modern otters eat plants, rodents, fish, and clams. Their ancestors could easily have snacked on the whole birds or small mammals (say, the size of an otter today).

It may have looked a lot like a otter scaled up to the size of a wolf, but S. melilutra occupied a very different place in the animal food hierarchy. Modern otters, Tseng told Live Science, aren’t big enough to worry large prey, so they don’t occupy an apex position in the food web. “We think this fossil otter was like the bear of its environment,” Tseng said, “one of the top predators.” Cute doesn’t always scale very well, but perhaps these fearsome beasts also had a softer side to go with those killer jaws.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook