President Grant’s Memorial Flowers Have Survived for 136 Years

They’ve just been sitting in the dining room all this time.

Ulysses S. Grant spent the last six weeks of his life in a hilltop cottage in upstate New York, a few miles from the Hudson River. The former president was broke, having lost all his wealth in a Ponzi scheme, and he knew he was dying—but he was determined to finish his memoir first, in the hopes that its royalties would be enough to support his wife Julia after his death. Grant had been invited to use this cottage as a writing retreat by William J. Arkell and Joseph D. Drexel, investors in a nearby hotel. The men’s generosity was strategic: They believed that having a president living on the property would give it historic value.

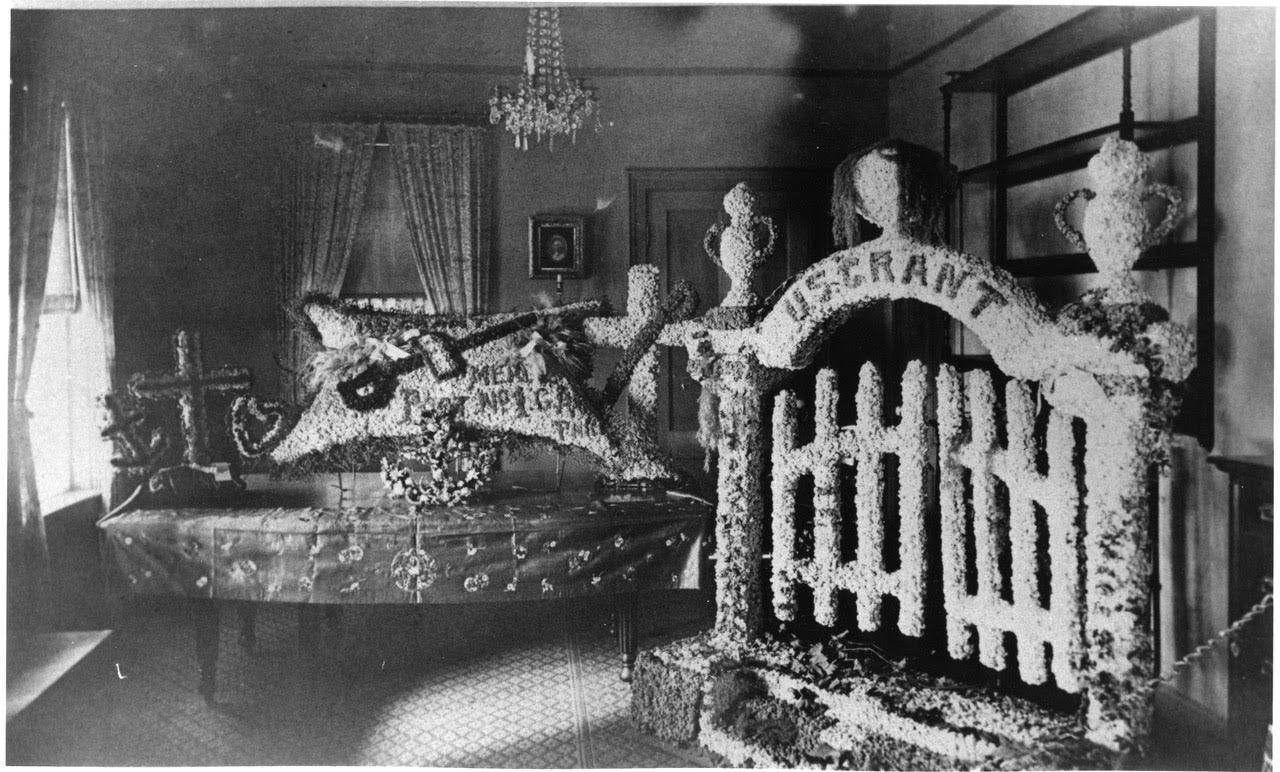

Grant died there on Mount McGregor, too, at 8:08 a.m. on July 23, 1885, and the cottage has remained almost untouched since, a shrine to the former president which now welcomes visitors in the warmer months. In the parlor, the mantel clock is permanently set to 8:08, and in the dining room—shrouded in darkness most of the time—sit the same massive flower arrangements on display at the first memorial to Grant, held at the cottage before a large crowd on August 4, 1885.

Today, when a tour guide turns on the dining room lights, visitors see much the same sight those mourners did: a six-foot-tall gate—like that which might stand at heaven’s entrance but emblazoned with the president’s name—entirely constructed out of dried flowers. Nearby a sword made of flowers rests on an oversized pillow of flowers surrounded by smaller floral sculptures in the shapes of crosses, a heart, and an anchor. After 136 years, Grant’s tributes have been drained of their bright colors. The petals are caked in grime, and some have fallen off over the years. But the set pieces are mostly intact, which makes them a historical anomaly.

Funeral set pieces like these were not unusual in the 19th century. The trend toward floral displays started to take root in American culture in the late 1860s and remained popular into the early 1900s. Most were constructed of flowers known as pearly everlastings. The small, cottony blooms were bleached and dyed in various colors and arranged in large and elaborate designs. Sticks were tied to the flowers and inserted into moss enclosed within wireframes to hold them in place.

“These are the only known set pieces that have survived intact, and that is because this guy Drexel decided that [the cottage] should be a shrine to [Grant],” says Robert Treadway, floral historian and author of A Centennial History of the American Florist.

Treadway first learned of the existence of these floral artifacts while watching a documentary about Grant. He could not believe they had survived for so long. Treadway set up a meeting with the Friends of Grant Cottage, which oversees the national historic landmark, to assess the displays in August 2021.

What Treadway discovered there surprised him further. Aside from the darkened room, occasional dusting, and a protective covering in the winter, there has not been much preservation work done on the flowers. The Friends of Grant Cottage thought that a protective layer of wax encased the flowers, but Treadway’s examination showed otherwise. The remarkably preserved flowers remain exposed.

Grant’s flowers are survivors, says Heidi Miksch, New York State conservator. But UV light is causing fading and rot, and humidity seeping through the fissures of the old home where the arrangements are stored has allowed microorganisms to thrive on the blooms. Fungi and bacteria—as well as insects—can digest artifacts. Moisture can also cause the stems and petals to twist, expand, and crack. Even the dust is dangerous—and dusting even more so. “Dust is an abrasive,” said Miksch, “The attachment of the petals to the core is weak. So, even the process of trying to very gently dust would be displacing petals.”

The question now is: How can Grant’s flowers be preserved for another 136 years?

Treadway first suggested a spray adhesive that florists use to hold the flowers’ heads in place. But that wouldn’t follow one of the rules of New York State conservators: Any changes conservators make to artifacts must be reversible. Ben Kemp, operations manager of the Friends of Grant Cottage, proposed creating a display case for the flowers, a tactic used to preserve a suit in the collection. And Miksch would rather leave the set pieces how and where they are. Putting the pieces into display cases would take up a lot of space and might hinder the interpretive integrity of the dining room, she says. Miksch recommended creating durable replicas of Grant’s flowers as they looked at the time of his memorial, based on images of the arrangements. The replicas would be displayed in the visitor center, and the originals would remain in the cottage’s dining room, unprotected and continuing to decay.

To help make their decision, the Friends of Grant Cottage and New York State will undertake a further threat assessment to determine which aspects of the current environment are doing the most harm to the one-of-a-kind 19th-century floral display. “There really is no guidebook for it,” Kemp says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook