Found: A Manuscript Sloppily Edited by Queen Elizabeth I

Her Latin was impressive, but her cursive wasn’t.

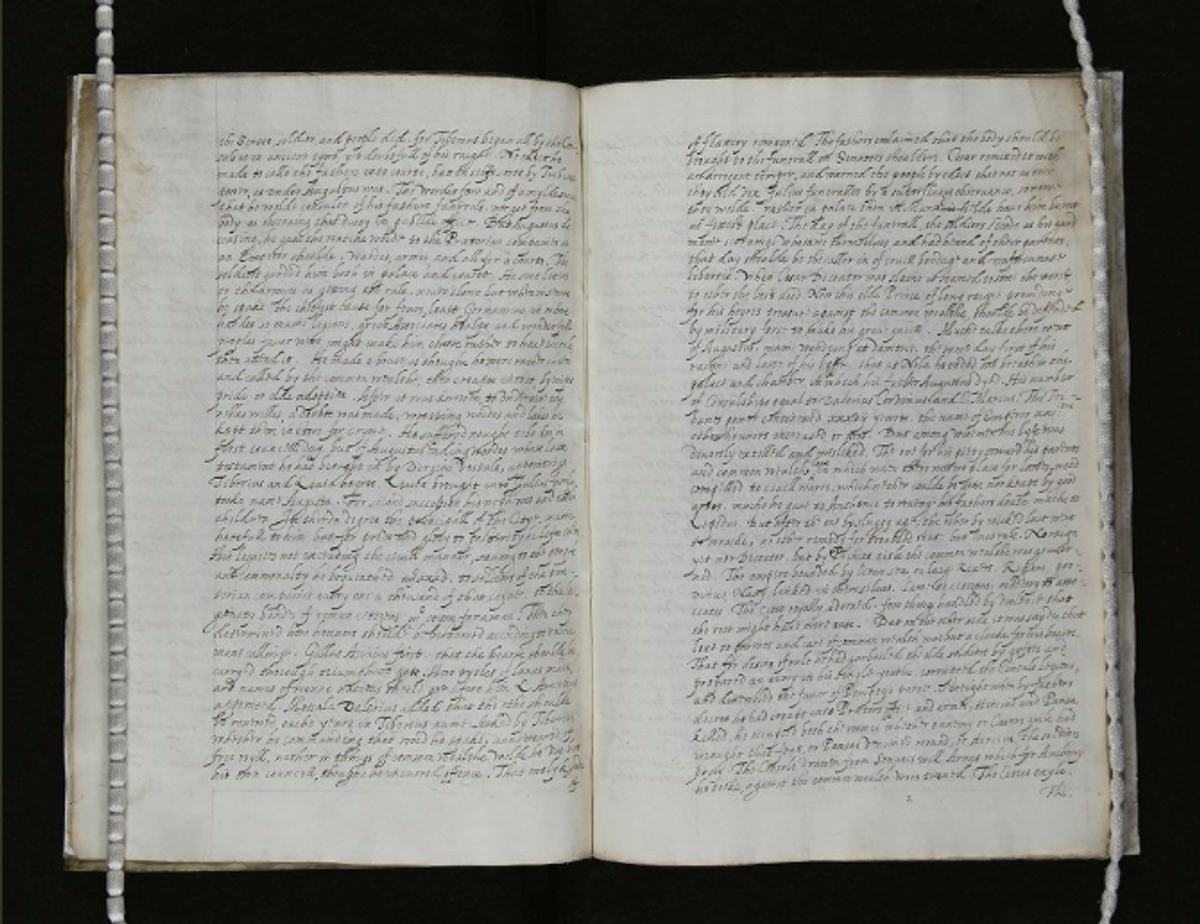

Properly executed, statecraft involves tons and tons of paperwork: documents for correspondence, for record keeping, for codifying laws, and, occasionally, for translating the work of early Roman historians. At least that’s what someone in the court of Elizabeth I of England was doing in the late 16th century—specifically a translation of the first book of Tacitus’s Annals from Latin to English—before the work ended up among the royal paperwork. The text was later revised by a second, sloppier hand. Now an article in the journal Review of English Studies suggests that the mystery editor of the manuscript, which has resided at London’s Lambeth Palace Library for 400 years, was none other than the Virgin Queen herself.

“There’s this chap called John Clapham, who produces a history of Elizabeth’s reign,” says John-Mark Philo, a fellow at Harvard University’s Center for Italian Renaissance Studies who identified the manuscript’s editor while on a fellowship with the University of East Anglia. “He’s Elizabeth’s contemporary, and he mentions some translation of Tacitus’s Annals.... I certainly didn’t expect it to be edited by the queen.”

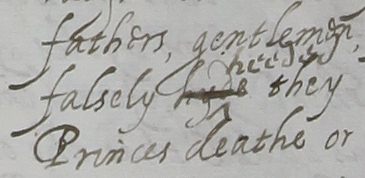

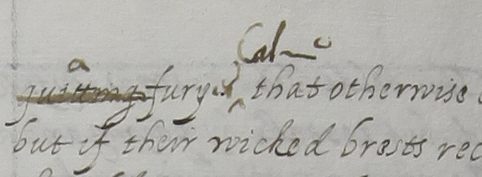

Tacitus’s work, written around the turn of the first century, found renewed popularity in Renaissance Europe. In the manuscript found in the library in Lambeth, Tacitus describes the peaceful period of the Roman Empire under Augustus. The work is penned in a neat, consistent, impressively legible italic across 34 pages. A few words throughout the work are struck through, with hasty corrections squeezed in above. The edits are peppered with royal terms such as “sovereign” and “reign,” nodding toward a monarchical perspective. But these word choices weren’t enough to identify the editing as Elizabeth’s—that took a modern understanding of old handwriting. In comparison with the royal scribe’s tidy hand, the edits are formed of a rather distinctive chicken scratch.

“The queen, and only the queen, uses this combination of an ‘M’ and an ‘E’—she’s almost making shorthand for ‘ME,’” Philo says. “It’s stuff like that in paleography. If it’s that weird, that odd, you’ve struck gold.”

The manuscript indicates that scribes serving the English queen likely had a multitude of duties. “The same scribe could be called in at one moment to copy an official letter concerning pressing state business,” Philo says, “and at another, the queen’s private meditation on Roman history.”

The manuscript was written on paper stock unique to the Elizabethan court. It was also watermarked with royal insignias that date the work to the final decade of the 16th century, when the queen was in her 60s. Scholars have previously taken note of how the monarch’s handwriting changed over the years. “When she’s a child, her handwriting is this absolutely exquisite italic,” Philo says. “As her reign progresses, you can see it falling apart. By the 1590s, it is wonderfully, fantastically, messy.”

The translation now resides in Lambeth Palace—directly across the Thames from the queen’s resting place in Westminster Abbey—alongside troves of other documents from her reign. (It is also the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury.)

“What I hadn’t appreciated before I started working on this translation is that Lambeth Palace hosts one of the largest collections of state papers from the Elizabethan era,” Philo says. “You think of the National Archives and the British Library, but actually Lambeth Palace, specifically for Elizabeth’s reign, has an absolutely fantastic collection.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook