The Manuscript of ‘120 Days of Sodom’ Has Been Declared a National Treasure

A nation embraces the Marquis de Sade’s controversial masterpiece.

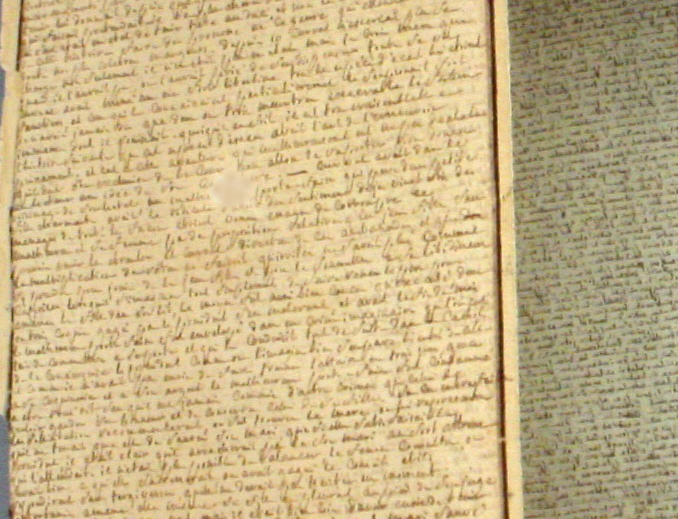

The surprisingly indulgent wife of the Marquis de Sade went to his cell in the Bastille to retrieve his belongings on July 14, 1789 (the prisoners had been moved before revolutionary crowds sacked the prison). Renee Pelagie de Sade was searching for one item in particular. Hidden in the room, he had told her, was a copper cylinder. And within that cylinder was Sade’s unfinished opus, 120 Days of Sodom, a sprawling monster of a novel described at best as a masterpiece of profane imagination and at worst as some of the foulest, cruelest pornography ever written. He had written it in secret, in a tiny hand, on a 39-foot scroll pieced together from smaller bits of parchment smuggled into the prison. Today that manuscript was declared a French national treasure, The Local reports, preventing its multimillion euro sale at Aguttes auction house in Paris.

Back in 1789, however, Pelagie left the cell empty-handed. Revolutionaries had looted the cell and the scroll appeared to be gone for good. When Sade found out, he later wrote, he wept “tears of blood.” It was, in fact, exactly where he had left it, hidden in a crevice in the wall. In the centuries since, the manuscript has bounced from aristocrat to erotica collector to erotica-collecting aristocrat—a checkered history that includes being stolen and smuggled overseas, held under lock and key by the authorities, sold fraudulently, and exhibited publicly. For almost any other book, the salaciousness of this series of transactions might overawe the story within. Not so Sodom.

Most recently, however, the manuscript was in the possession of disgraced (appropriate, somehow) French investment firm Aristophil, which was decried as a Ponzi scheme and shut down two years ago, taking a billion dollars of investor money with it. Some 300 treasures from its coffers were due to be sold at Aguttes this week, including an original copy of André Breton’s “Surrealist Manifestos.” This, too, was declared a national treasure to prevent its leaving France after a sale. The auctioneer, Charles Aguttes, said the French ministry of culture had promised to buy the two works at international market rates—around $12 million in total.

Often referenced and seldom read, 120 Days of Sodom has undergone a surprising rehabilitation since its first publication in 1904, by German sexologist Iwan Bloch. The first release of scholarly editions of Sade’s works, in the 1950s, led to publisher Jean-Jacques Pauvert being prosecuted for obscenity and initially spanked with a 200,000-franc fine. Certain English translations remained banned by British Customs as late as 1983. Then, in the 1990s, 120 Days was released as part of the prestigious Pléiade series of French canonical works, in a three-volume edition. These are printed on gossamer-fine papier Bible. Though this thin paper stock is not reserved for Bibles, it did inspire a catchy tagline for the series: “Hell, on Bible paper.” That this work, an assault on authority, most people’s sensibilities, and the very notion of provocation, should find its way into the collection of French national treasures would likely have tickled its gleefully perverse creator.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook