Striking Satellite Images of Cities on the Brink

A fresh perspective on the fragility and resilience of our world.

From the window of her office in New Haven, Connecticut, Karen Seto sees a sea of green. A professor of geography and urbanization science at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Seto can observe in that scene seemingly countless different shades, shapes of leaves, and natural textures. It’s familiar and pretty, but there’s only so much that our eyes can wring from a view like that. There’s a lot that we can’t see.

If Seto could see in the near-infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum—outside of the range of human vision—a glance would reveal a wealth of other information. She could ascertain which leaves are overheated, or parched. In the adjacent buildings, she could peer beyond brick, glass, or steel, to the materials that comprise them. And if she could take this all in from space, she could see how her view fits in among the university’s Gothic roofs, sports fields, and criss-crossing walking paths.

But we can see like that, with the right technology. “Just as dogs can hear sounds inaudible to humans, sensors aboard satellites are able to ‘see’ what our eyes cannot,” write Seto and her coauthor Meredith Reba, a research associate, in their new book, City Unseen: New Visions of an Urban Planet. Seto and Reba dove into a trove of largely open-access satellite images of cities, then used image processing tools to adjust them, and highlight hidden dynamics or patterns that emerge over time. They can show the way heat bakes different parts of an urban area, how much sediment is building up in stagnant water, or how a landscape sprouts back to life in the aftermath of a disaster.

The massive quantities of raw data produced by these sensors can be overwhelming, so Seto and Reba began fiddling to home in on specific spectral combinations. Their tinkered-with images are thrillingly uncommon ways to see a place—familiar or otherwise—and document what happened there or what could lie ahead. Some of their formulas put the spotlight on environmental challenges—from melting ice to standing water to the long tail of nuclear fallout. The images they produced can be stark and startling.

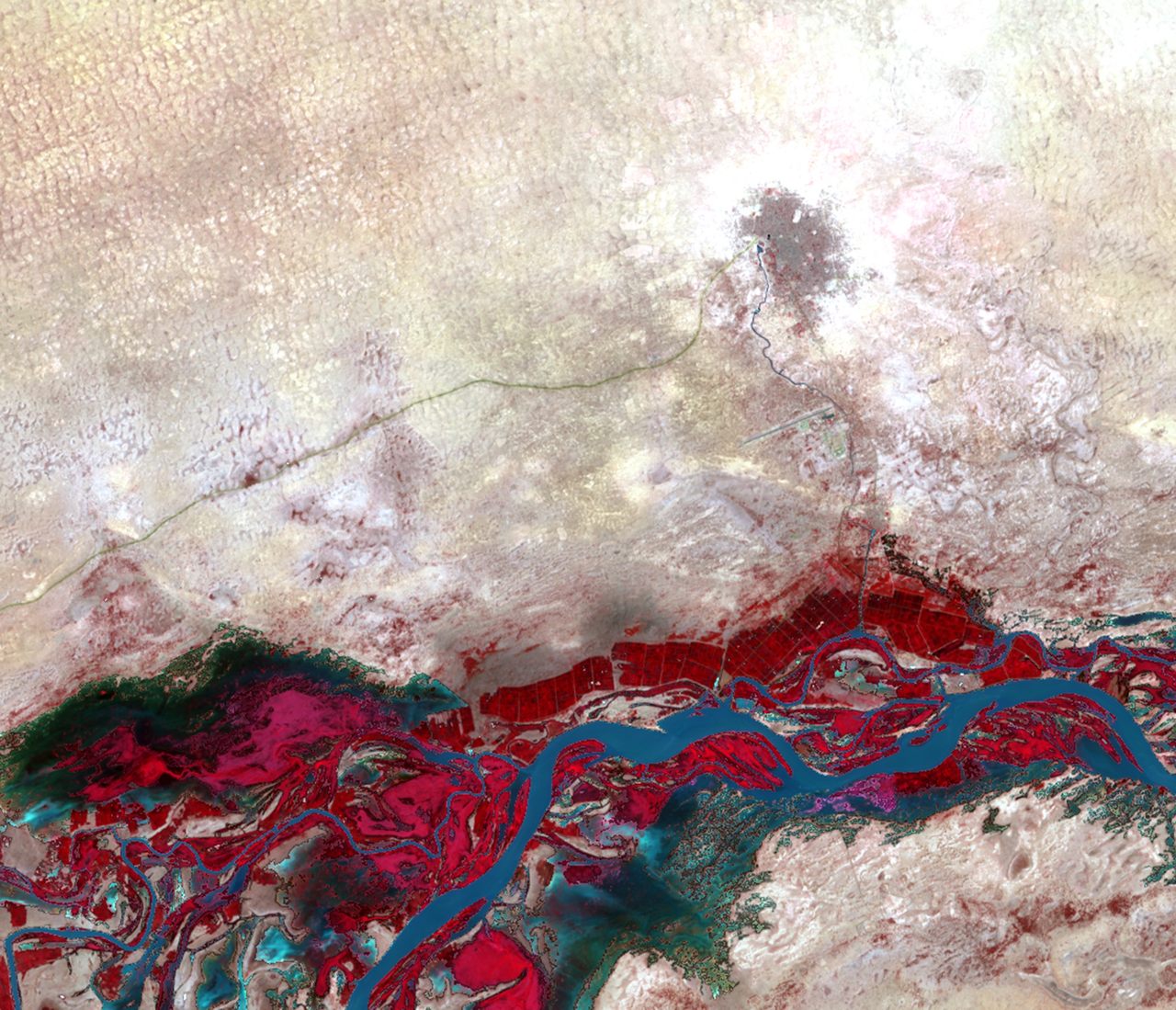

In Seto and Reba’s images, a tornado’s path through Joplin, Missouri, is visible as a purple gash. The flanks of the Niger River, in Timbuktu, Mali, are a scalding red. Stagnant silt in Chittagong, Bangladesh—from landslides, floods, and insufficient infrastructure—is a diffuse turquoise. The land around McMurdo Station in Antarctica is a rich, velvety brown against the white-blue ice surrounding it.

There’s a lot that can be learned from seeing the world this way, at a distance, with different eyes. “The aim was to use these images to draw the reader in,” Seto says. “To show, ‘Hey, we’re living on this incredibly beautiful planet, but it’s incredibly vulnerable, as well.’” If the ice around McMurdo melts, for example, it could flood the instruments and grind research to a halt—and be a harbinger of widespread climatic changes that would impact cities all over the world.

The images also draw attention to the resilience of both cities and nature. In the satellite images of Joplin, Seto and Reba made the vegetation appear spectacular green, and the structures and bare soil a deep purple. The tornado—one of the costliest and deadliest twisters in U.S. history—churned up both of these land covers, and its path mutes both into a light-purple smear. (The near-infrared data, with false colors, shows these differences more starkly than visible light would.) In another image, taken four years later, the gash has faded. Vegetation sprouted back to life, houses were rebuilt, and the city restored its street grid. “Using remote sensing imagery accentuates the difference between the two land covers,” Reba writes in an email. In the later image, “We are starting to see the clear distinction between urban structures and vegetation again.”

The same goes for the area around Pripyat, Ukraine, but in the opposite direction. Before the 1986 nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, the area was tidy, gridded cropland. Decades later, without people and their efforts to tame the landscape, wild vegetation reclaimed those areas and the straight lines began to fade. A fresh perspective can make the world seem like an entirely new place.

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from Seto and Reba’s City Unseen.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook