See Yellowstone’s Beauty Change Through The Ages

How one photographer rephotographed the sites from an 1871 expedition.

Left, TOP: No. 303. THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, with pack-train, en route upon the trail between the Yellowstone and the East Fork. Right, the area today. (All historical photos: William Henry Jackson; all contemporary photos: Bradly Boner)

The region now known as Yellowstone National Park was, in the late 1860s, largely a mystery to the U.S. Congress. There had been reports of the area’s natural beauty from trappers and explorers, but their descriptions were often greeted with skepticism. In order to find out exactly what lay out West, and how the land should be used, in 1867 the Government commissioned a series of surveys.

In 1871, Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden’s Yellowstone expedition took place. While there had been surveys previously, this one would prove to be critical. Not only was Dr Hayden a geologist, he also brought with him a team of scientists, two artists and, for the first time, a photographer: William Henry Jackson.

For Jackson, an established photographer who had fought for the Union in the Civil War, this was the beginning of his eight-year tenure as official photographer for the surveys. Jackson’s equipment, which included glass plate negatives, chemicals for processing, tripods, weighed several hundred pounds, and needed to be carried separately by pack mules.

Jackson’s photographs were shown to Congress as part of Hayden’s findings, and offered irrefutable proof of the natural beauty of the area. The photographs were more than just evidence; they also helped Yellowstone to become what it is today. Legislation was proposed to make the area a park, and on March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the law that “set [Yellowstone] apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit of the enjoyment of the people.”

Nearly 150 years later, photographer Bradly Boner retraced Jackson’s footsteps and rephotographed the same sites from that influential expedition. His upcoming book, Yellowstone National Park: Through the Lens of Time, will display, side-by-side, the Yellowstone of 1871 and the Yellowstone of today. Atlas Obscura spoke to Bradly about the impetus for this project and the timelessness of Yellowstone.

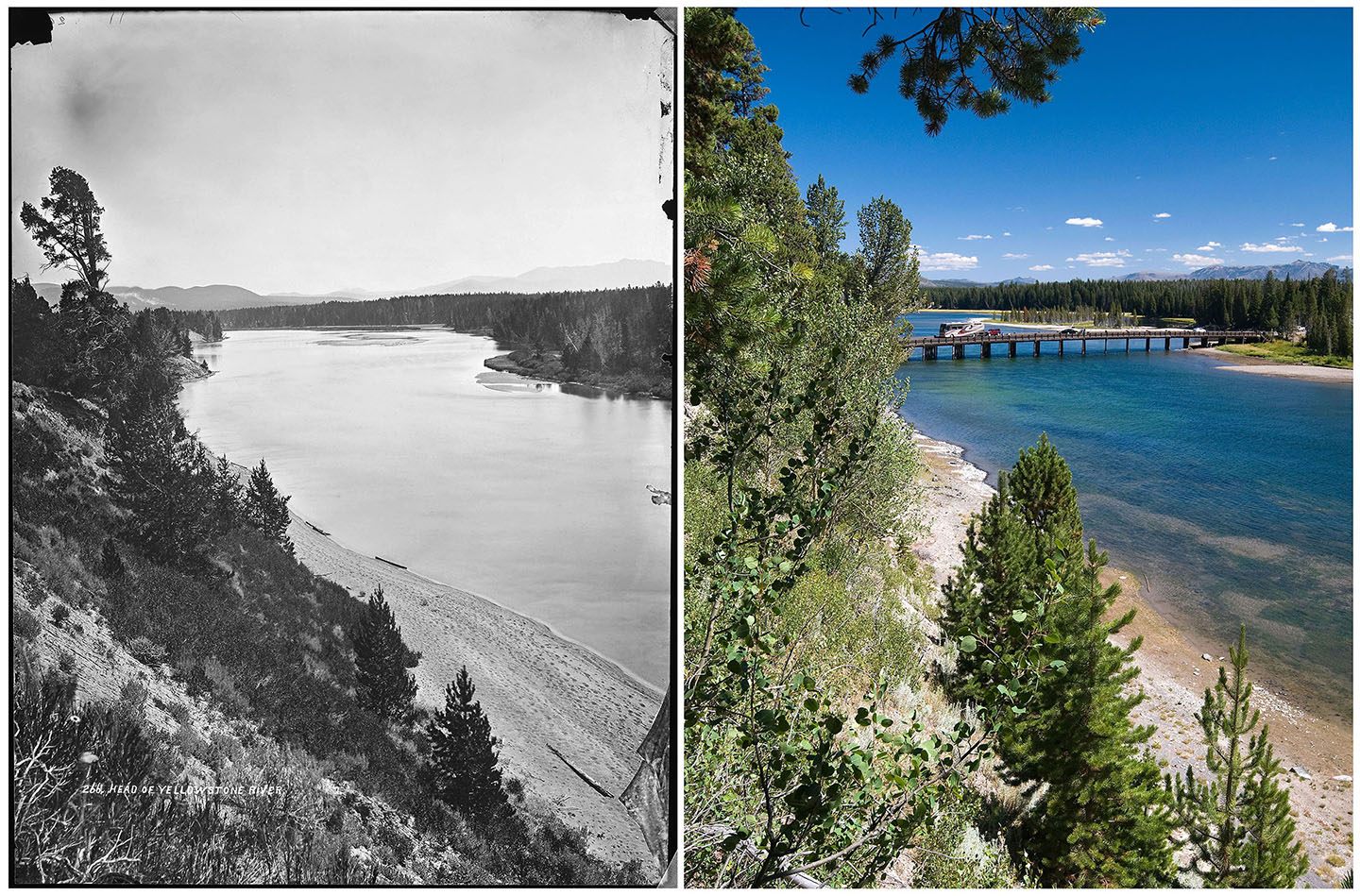

Left, No. 266. YELLOWSTONE RIVER where it leaves the lake, looking north. Right, Fishing Bridge now spans the Yellowstone River just north of where it exits Yellowstone Lake, and trees and other vegetation line the steep west riverbank in the foreground.

What prompted you to photograph the Yellowstone vistas as a ‘then and now’ project?

I grew up in the Black Hills of South Dakota, and I’ve always been interested in the area’s history and the history of the American West in general. In the early 2000s a photographer [Paul Horsted] did a “then and now” book of contemporary photographs for the first pictures ever taken in the Black Hills—a photographer had made the images during an 1874 expedition led by Gen. George A. Custer to explore and map the region. I was intrigued by the adventure of finding the original photo points, and in seeing the side-by-side comparisons, how the landscape had changed over time.

Living near Yellowstone made me wonder if William Henry Jackson’s images of the region had been re-photographed. After a little research I found that, while there had been a few re-photography projects here and there, no one had ever re-photographed all of Jackson’s 1871 images. In all, I made contemporary images for more than 100 of Jackson’s photographs from the 1871 Hayden Survey to the Yellowstone region.

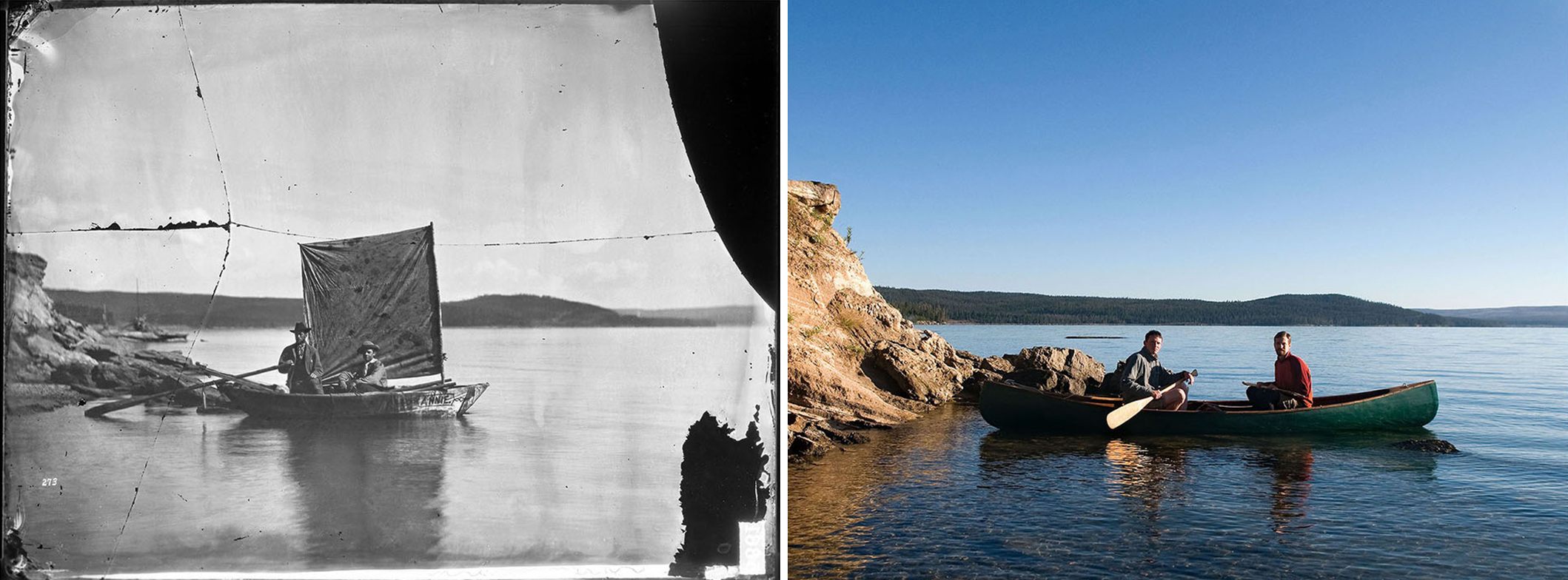

Left, No. 273. THE ANNA, the first boat ever launched upon the lake. Right, Recreating the photograph with Brad Boner, left, and Matthew J. Reilly, PhD, in the canoe used in the present-day research project to navigate Yellowstone Lake and locate several of Jackson’s 1871 photo points.

What was the significance of William Henry Jackson’s photographs? What do they mean to you personally?

Though there had been two private expeditions into Yellowstone (1869 and 1870) before Hayden led his government survey to the region in 1871, neither party brought a photographer. Their accounts of the wonders they had seen seemed extraordinary and were often dismissed as exaggerated campfire tales. The new medium of photography offered a direct reflection of subject matter; written description and art could be embellished, but pictures couldn’t lie. The scientific fact-finding nature of Hayden’s government-funded survey also added a great degree of credibility. When legislation to establish Yellowstone National Park was introduced in Congress in late 1871, Hayden arranged for a collection of scientific specimens gathered during the expedition to be exhibited in the Capitol rotunda, including Jackson’s photographs. Without them, skeptics again may have dismissed description as poetic exaggeration, even though Hayden was one of the most respected geologists of his time. Hayden himself admitted several times that much of Yellowstone’s landscape was beyond words. While no single item can be credited with securing national park status for Yellowstone, Jackson’s photographs served as tangible, visual proof that the curiosities Hayden and his team described were no embellishment.

For me, these photographs represent the first glimpse at a pristine landscape, untouched by modern man. Even today the American West has a sort of untamed ruggedness about it and evokes a sense of adventure. Jackson was one of the first to use photography to document the West, so these images tell the story of what Yellowstone was like before millions of tourists began visiting the park every year.

Left, No. 298. THE GROTTO IN ERUPTION, throwing an immense body of water, but not more than forty feet in height. The great amount of steam given off almost entirely conceals the jets of water. Right, The eruptions of Grotto Geyser can last anywhere from one to 24 hours and can splash water more than 40 feet high.

How did you plan out logistics for the shoot?

Since I live relatively close to Yellowstone, I was often able to drive up to the park for a day or a long weekend. Even then I was sometimes thwarted by bad weather or heavy smoke from forest fires burning in the region that obscured the landscape and, in general, would have made for poor photographs. There were other trips that were more logistically complex and took some advance planning. For instance, a friend and I spent 11 days paddling a canoe around Yellowstone Lake to find about a dozen of Jackson’s photo points. Another big task was hiking to Mirror Lake on the Mirror Plateau, which required a one-way hike of about 11 miles, four of which were off-trail, to re-photograph just four of Jackson’s images. Once I found any given photo point there was often a lot of waiting for the light to be just right in order to make the best image.

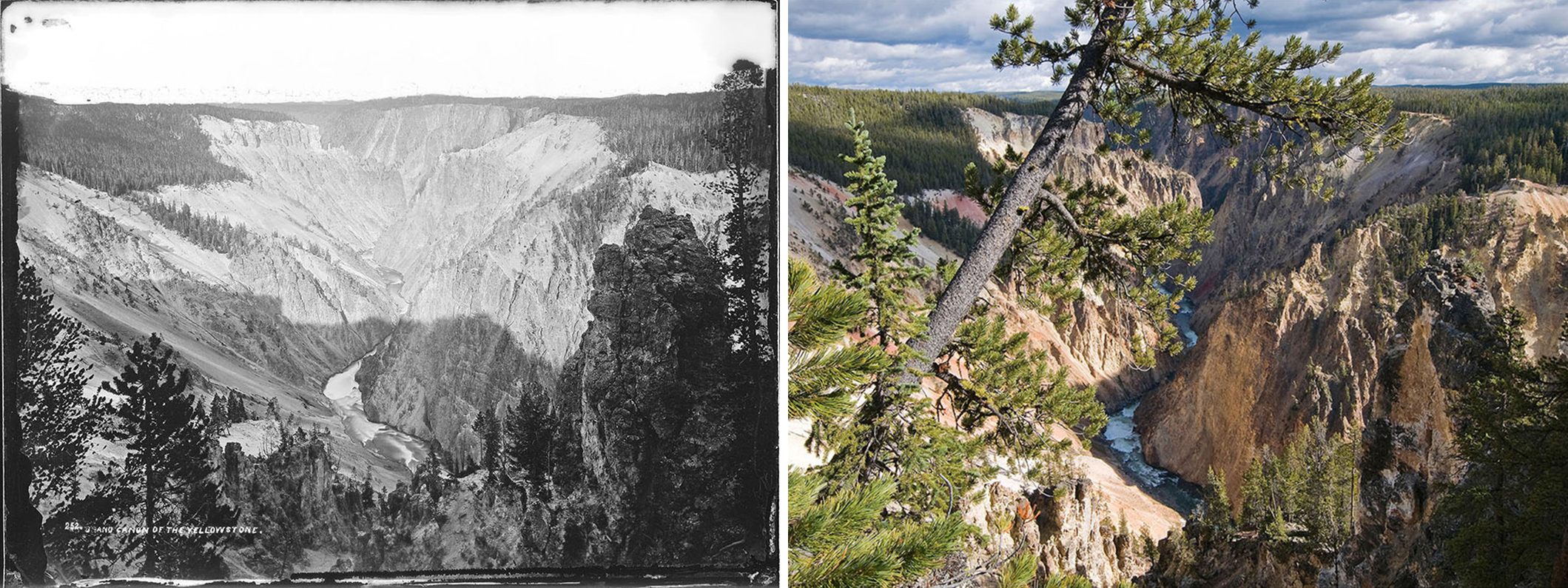

Left, No. 252. GRAND CAÑON. West side, one mile below the falls, looking down. Right, a pine tree bisects the scene from where Jackson made this photograph looking down the Grand Canyon from near the Grand View overlook on the west side of the canyon.

What are your thoughts on the ‘then and now’ comparison, and what do you think it says about the future of Yellowstone?

I was pleasantly surprised to see that, for the most part, the landscapes of Yellowstone remain remarkably similar to how they appeared when Jackson photographed them almost a century and a half earlier. After completing this project I was comforted to know that my kids, my grandkids and beyond will have the opportunity to see a Yellowstone that is more-or-less unchanged from when I first experienced it as a child, and from when Jackson first photographed it almost a century and a half earlier. In that regard, we’ve been given a gift, but it is also a reminder that Yellowstone doesn’t really belong to us. It always belongs to future generations, and we are merely stewards of the world’s first national park. Yellowstone, with all its rivers, canyons, geysers, mountains, and lakes, has been here for millions of years before we came along. It will remain for millions more when we are gone. But while we are here, it is ours to care for.

Left, No. 214. GROUP OF LOWER BASINS (Mammoth Hot Springs); Right, as it looks today.

Why do you think Yellowstone National Park has captured people’s interest and imagination so strongly, for so long?

Early explorers called Yellowstone a “mythical wonderland” because it was something so incredible that it seemed it could only come from imagination. Even then, Yellowstone is considered by many to be beyond description, and no words, painting or photograph could do it justice—it must be seen to be truly experienced.

There is a concept in philosophy known as the sublime, which basically refers to greatness beyond what one could previously comprehend. Yellowstone evokes both power and fragility, and is so unique, grand and beautiful in so many ways—boiling hot springs, spouting geysers, towering waterfalls and a massive, pristine lake—it is almost impossible not to be captivated by it.

To learn more about Bradly’s book project, please visit his website.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook