The Refined, Scandalous Art of Japan’s Traditional Woodblock Tabloids

Shinbun nishiki-e were the country’s answer to penny dreadfuls.

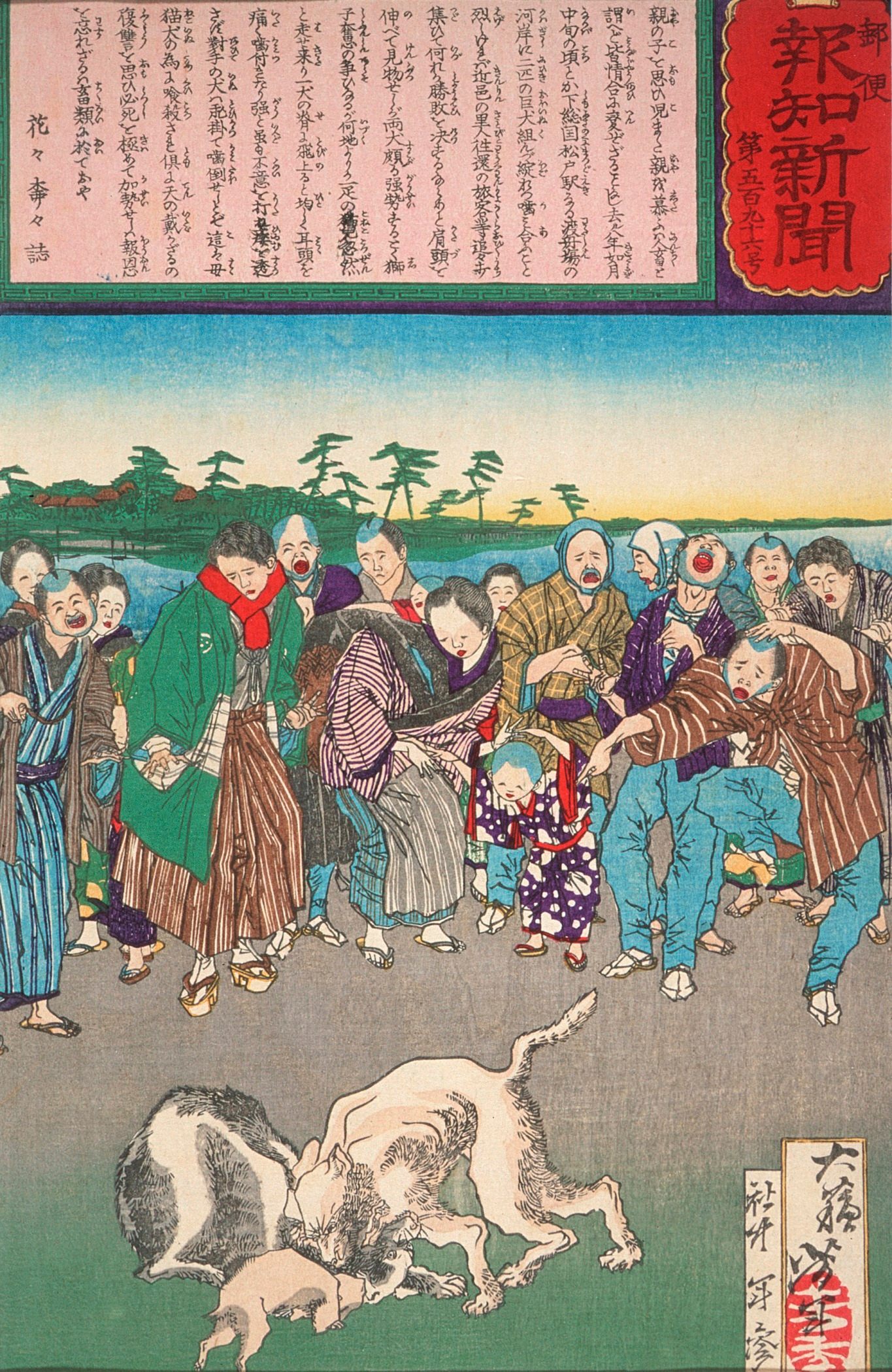

In 1875, the residents of Tokyo were alerted to a murder. Hundreds of miles away, in the remote mountains, a lonely man named Gitarō had been visited by a local woman who sold old clothing. She asked to stay the night; cordially, he invited her in. Then, far from the eyes of any prying neighbor, he stabbed and killed her, took her money and possessions, and cut off her head. Months later, a dog walked through the village with her severed head in his mouth. The corpse was found, wrapped in a straw mat in the man’s home, and he was caught and arrested.

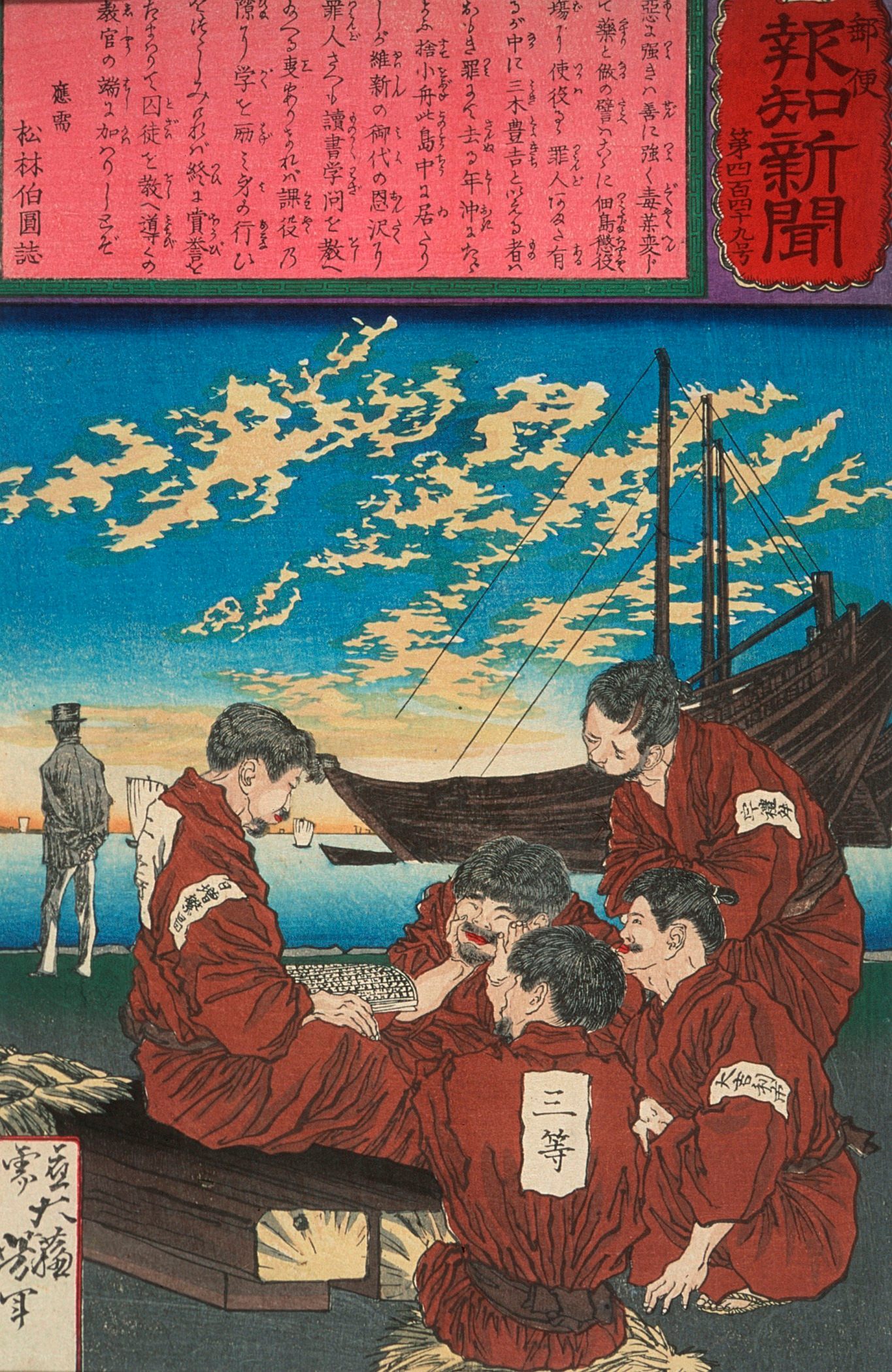

Stories of this sort—lurid, sensational, violent—were the bread-and-butter of Tokyo’s early tabloids. Printed in the mid-1870s, they were produced by some of the country’s most able artists, using traditional woodblock printing. For a time, it was a potent combination: the country’s most salacious stories, gorgeously illustrated and framed like the dust jacket of a book. Around 1,000 editions of these were produced, before changing technology ended the practice. These were the shinbun nishiki-e—a kind of Japanese analogue to the penny dreadful, with a moralistic twist. In one edition, the text concludes: “Ah, the moral powers of our land of the gods. That Heaven used a dog to reveal a bad man’s hidden evil is something to fear and revere.”

Earlier in the 19th century, people in Japan got most of their news from illustrated broadsheets called kawaraban. They told scurrilous tales of murder and suicide, gave details about natural disasters (of which Japan had many), or spun yarns about monsters and the unknown. Rather than having regular print runs, kawaraban came out only when there was something to say—published, quick and dirty, in a single color. The sheets were approximately twice the size of today’s letter paper and sold from towering piles by furtive salesmen on street corners. (You could buy four for the cost of a bowl of noodles.)

The 1870s brought something of a revolution in Japanese media. Publications today considered Japan’s first modern newspapers sprung up one after another, providing more authoritative views on Tokyo’s stories. Not everyone could read them, however. Printed only in complex kanji, with minimal illustration, they were out of reach to the uneducated. And so shinbun nishiki-e arose to fill the gap and provide an alternative revenue stream for struggling woodblock publishers.

Like the kawaraban, they told wanton stories, sometimes lifted from the “mainstream” press and reprinted under the original newspaper’s name. There was still kanji text, certainly, but also phonetic hiragana, a simpler syllabary. And they included a vivid illustration for the roughly 60 percent of the population that was entirely illiterate. Shinbun nishiki-e were designed to be accessible and appealing to all, and as a consequence, they sold like onigiri.

In these papers, editorial coverage tended towards the sensational—illicit love, ghosts, freaks, revenge. Even when they had some basis in fact, the reporting was only slightly better than in the kawaraban, and multiple competing accounts of the same event might swirl simultaneously. Stories might have been related weeks or even years after they had taken place, rewritten in splashy, didactic copy, sometimes with a moral.

In fact, embellishment and even fabrication do not appear to have been particularly bothersome to those in power, writes Rebecca Salter in Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards: “The authorities, who may have known the full facts, were content with the confusion sewn by this uncertainty, as long as one version of a story did not appear to gain ascendancy as the correct one.”

Without any kind of censorship in place, therefore, images went quite explicit: the gang rape of someone’s girlfriend, or the bloody mouth of a man poisoned by his wife. Others were decidedly political—rebels defeated, or the tragic tale of a government soldier reuniting a woman with her husband’s body. A controversial edition in which a woman serves her husband his mistress’s genitals as sashimi is a riot of color—and showed that there was a limit to how far these papers could go. That one provoked so much outrage that its publication was stopped. (Whether this was due to the high rank of the husband or the gratuitousness of the image remains a mystery.)

But for all their gore, the images are quite beautiful. The lines and colors were often as subtle as their subjects were shocking. Many artists who produced them were among the best in the country, including Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, who contributed mostly to the paper Yubin hochi shinbun and Utagawa Yoshiiku, who cofounded and mainly drew for the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. People visiting the city bought them as souvenirs and then took them back to the countryside, so friends and family could gawp at the scandal and sophistication of metropolitan affairs. “My god!” wrote one visitor. “What a sign of civilization! What a sign of culture!” For foreigners, they had far less appeal: The text wasn’t legible, and the pictures far less appealing than “Japanese-y” geishas, cherry blossoms, or pastoral scenes.

Shinbun nishiki-e were never intended as art. When profits dwindled, then, they were extinguished like a candle. “Real” newspapers were increasingly illustrated, and a rise in Western printing techniques made these traditional woodblock images seem dated. It was also a slow, laborious way to produce papers—especially if no one was buying. Movable type was faster, Western paper was heartier, and, like locomotives or the telegraph, both were seen as signs of progress. By the end of the 1870s, the shinbun nishiki-e illustrated pages were all but gone, with their one-of-a-kind illustrations as valueless as yesterday’s newsprint.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook