What’s Really Behind the Ghost Lights of Colorado’s Silver Cliff Cemetery?

Tucked between rugged mountains, this lonely graveyard is home—allegedly—to ethereal, glowing orbs that dance among the headstones.

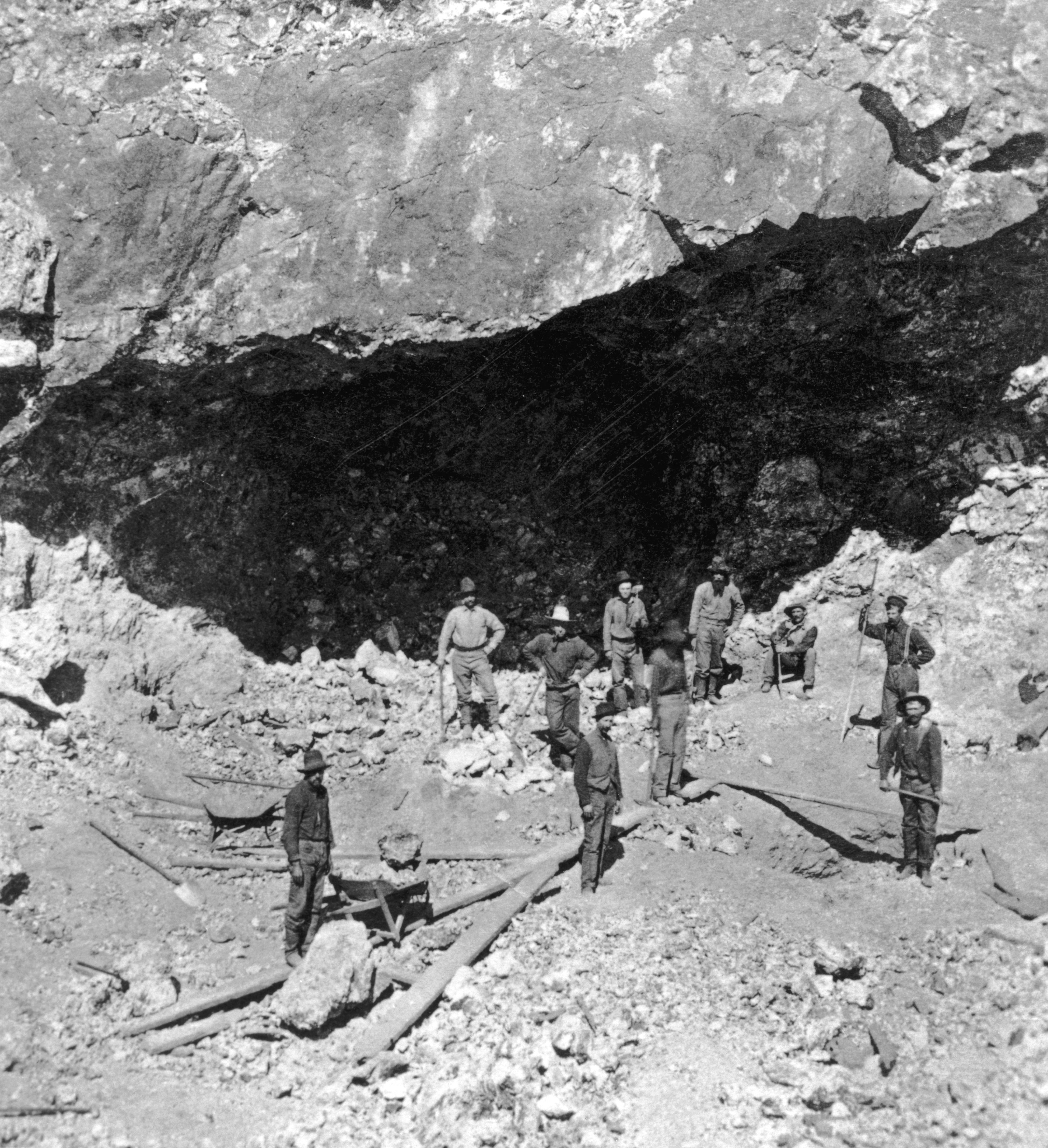

The town of Silver Cliff sits in a high valley between Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains, rising like sawblades more than 14,000 feet, and the aptly-named Wet Mountains, which top out around 12,000. It started out as a mining town in the late 1870s and, despite regular snow eight months a year, chilly temps, and rugged terrain, a silver boom quickly made it the state’s third-largest town.

By the early 1880s, more than 5,000 people called Silver Cliff home, including three miners who were walking home from a bachelor party one dark night. They opted for a shortcut through the town’s cemetery and, as they walked past the graves, ghostly balls of blue and white light began to dance among the tombstones.

That sure hurried them to town, where their story spread, getting muddled in the retelling. In some versions, it actually happened in the 1890s—or perhaps this was a second, similar incident. Sometimes a miner, trying to catch the lights with a knife, slices into his own raincoat. In some tellings, the whole town turns off its lights one night to prove the phenomenon isn’t just reflections off the headstones. The truth, like the lights themselves, is elusive.

Today, Silver Cliff has around 600 residents, and the cemetery shows its age. Wildflowers and high-prairie grasses rustle and bend in the valley’s notorious winds, brushing against tilted, worn headstones and advancing over the bricks that mark plotlines. “They all need to be taken care of,” says Silver Cliff Museum curator Richard Posadas, who has come to the cemetery. It’s his first visit in a while, so the weeds around his great-grandparents’ graves are encroaching more than he’d like. The couple moved here long ago in hopes the dry air would cure his great-grandmother’s tuberculosis.

Posadas points out a nearby rock with a plaque on it, a monument to 10 miners who died in a mine explosion in 1885. Some of them are buried here as well, he says, a reminder that Silver Cliff was a dangerous place because mining was a dangerous job. During the silver boom era, local papers such as the Silver Cliff Rustler and Wet Mountain Tribune recorded miner deaths and mishaps—but there seems to be nothing from that time about the ghostly lights.

Bryan Bonner, founder of the investigative group Rocky Mountain Paranormal, says the first written mention he’s found of them appears in the 1956 Wet Mountain Tribune article “Silver Cliff Cemetery Ghosts Carrying Own Lights at Night.”

“One evening last week, some of the younger set of the community were taking a nocturnal ride,” reads the article. “As they passed the cemetery, screams of terror came from the feminine occupants of the car as they beheld numerous eerie lights dancing among the tombstones.” There’s nothing in the 1956 article about the lights ever being seen before, suggesting the midcentury incident may have actually been the first sighting, embellished over the years with claims of drunken miners and slashed raincoats.

“We see that with most of the cases that we deal with,” says Bonner, adding that his team is usually able “to track it back to something as simple as a bunch of teenagers out, the boys trying to scare their girlfriends.”

The story reached national prominence in 1969, when National Geographic published a feature on Colorado. The article concluded with a trip to the Silver Cliff Cemetery, where “dim, round spots of blue-white light glowed ethereally among the graves.” Some believers today say National Geographic published an investigation into the lights. In reality, it’s a few paragraphs in a piece that spans tens of pages.

Given the way the truth has twisted over time like prairie grass in the wind, Bonner had his doubts about the lights. Nevertheless, his team went to investigate, camping at the cemetery with cameras to see what they could see.

The first thing they noticed was the reflectivity of tombstones, which could be bouncing town’s lights off their surfaces. When he visited, someone had also put up blue reflectors throughout the property. “If you’re way down the hill from there and hit one of those with any light whatsoever, they reflect really well,” he says.

He thinks that might explain the lights. Or, he says, it could be a phenomenon with the eerie name of the “prisoner’s cinema.” When your eyes don’t get stimulated by photons—if, say, you work in a mine, or walk home in a place that even today is considered a “dark sky community”—you sometimes hallucinate lights. “When you’re in that type of darkness, your eyes start messing with you,” Bonner says. “And then, of course, the mind being the terrible thing that it is, it starts messing with you.”

Bonner isn’t saying the lights aren’t real—and he’s not saying they aren’t ghosts. “I can’t prove a place is not haunted,” he says. “You can’t prove a negative.”

Whatever they are, the Silver Cliff sightings of ghostly lights are not unique, says University of Manitoba’s Christopher Rutkowski, whose areas of investigation include UFOs and lower-sky luminousness. Similar phenomena, sometimes called spook lights or will-o-the-wisps, have been spotted elsewhere in North America, as well as Indonesia, Australia, and other places, sometimes associated with cemeteries or notable geological features. “Depending on who you talk to, these are either apparitions of ghosts or spirits, or some scientific anomaly,” Rutkowski says.

Rutkowski himself has visited various ghost-light hotspots. He’s found that the otherworldly lights are sometimes just car headlights, bending or reflecting weirdly, or trains in the distance. A few have involved gasses, typically methane mixing with phosphine, that bubble out of swampy areas as organic matter decays. Other potential natural explanations include triboluminescence, which makes minerals glow when scraped or crushed. And sometimes, Rutkowski admits, people are just imagining things. “There’s a number of possible explanations, all of which are fascinating,” says Rutkowski. “But people are interpreting them in any way they want, depending on their beliefs.”

That is, after all, what people always do. In the case of cemetery lights like Silver Cliff’s, people can interpret the glow as a connection with those who are gone. “To have some hope that loved ones are still part of you, and part of the landscape, is a very powerful motivator,” says Rutkowski.

It motivates belief, and it motivates road trips. Today, out-of-towners still cruise the cemetery. “They drive down, maybe get something to eat, some buy some land,” says Posadas. “We get a lot of free marketing. It’s good in those ways.”

As the sun sets behind the Sangres, golden hour descends upon the cemetery. The world appears through a yellow lens that sharpens the edges of everything. Shadows of weeds and headstones grow long. Lights wink on in town, to the north. As it gets darker, the mountains disappear: the lights of homes and cars partway up their slopes appear to hover in the thin air.

On Bonner’s investigatory camping trip, he didn’t see anything weird, and neither did his cameras. But he did feel a connection. And so he fronted the $100 to buy a plot for himself, so that when he’s no longer here, he can be here.

Posadas hasn’t witnessed any weird lights either, and doesn’t know anyone who has. But he’s happy for the legend to persist. Silver Cliff is no longer a boomtown, but its past and present come together in its cemetery, home to miners and others who have tried their luck there over three centuries. The ghost lights, real or imagined, help keep their stories alive.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook