Smell You Later, Donald Trump: How Roses Get Their Names

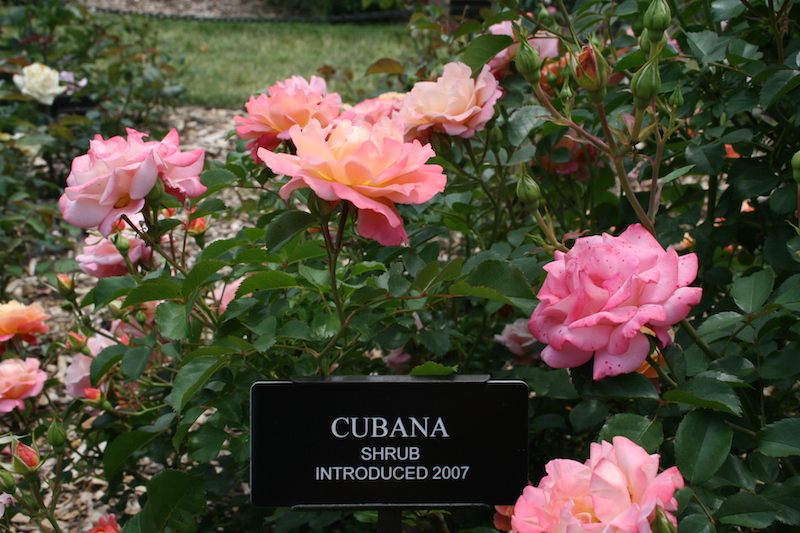

Rose names often make very little geopolitical sense: Cubana was bred in Germany, and isn’t heat-resilient enough to grow in Cuba.

Rose names often make very little geopolitical sense: Cubana was bred in Germany, and isn’t heat-resilient enough to grow in Cuba.

(Photo: Cara Giaimo; all photos taken at the Cranford Rose Garden unless otherwise indicated)

Walking into the Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s Cranford Rose Garden is kind of like going to a fragrant, time-warped celebrity function. Dick Clark swaps pollen with a pink-cheeked Auguste Renoir. Betty White shares a tube of water with Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Bees swarm like paparazzi, and starstruck people lean over for a better view, or to take a long whiff.

Of course, these bedfellows aren’t famous painters or TV personalities any more than Seabiscuit was a cracker. They’re roses.

Is “William Shakespeare 2000” a robotic playwright? The long-lost third member of Outkast? Nope, just a rose cultivar that marries a “strong, warm Old Rose fragrance” with a “neat, upright shrub.” (Photo: Gryllus70/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Like show dogs or vacation homes, rose cultivars are too precious (and too numerous) to get by on their common names. “Modern roses today are hybrids of hybrids of hybrids,” says Melanie Sifton, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s Vice President of Horticulture. Anyone who successfully comes up with a new cultivar gets to christen it, and of the hundreds registered each year with the American Rose Society—the organization tasked with “recording, publishing, and establishing priority on rose cultivar names”—a fair percentage are named for famous people.

The Delany Sisters rose, named after civil rights pioneers Sarah and Bessie Delany, has double petals. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Roses and the celebrities they’re named after have some broad things in common: they’re attention-getting and sensorily overwhelming, and they look great on camera. Often, they have more specific similarities, too. “You could do a whole tour just on the personalities that are attached to the roses,” says Sifton. The Dolly Parton rose, for example, “is known to be a great performer, and it’s brash…this beautiful deep red color.” (She plans on visiting it this winter to see if its hips are big.) Julia Child’s is a buttery yellow that smells like licorice, and Archbishop Tutu’s blooms all the way into winter, its “sparkling” red petals “calling out greetings from afar.”

Archbishop Tutu officially approved his rose, which was presented to him on his 75th birthday. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Until the mid-20th century, reports gardener Constance Casey, most roses were named after actual kings and queens, or “a few deceased notables.” It wasn’t until the 1950s and ‘60s that breeders, hoping to draw customers, branched out into Hollywood royalty. Now people like Celine Dion and Donald Trump pay tens of thousands of dollars to “walk the fields” of major growers and choose a bloom that reminds them of themselves.

Donau, a Kentucky Derby-winning racehorse, probably did not choose his own rose. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Donau, a Kentucky Derby-winning racehorse, probably did not choose his own rose. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

In established gardens like the Cranford, you’re still more likely to see older celebrities, thanks partly to the namers’ demographics (rose breeders themselves skew older—many are retirees, flown to warmer climes), and partly to plain old statistics (there are more older breeds around to choose from). Some have faded from the public consciousness entirely: Aviateur Blériot, once revered as the first person to fly across the English Channel, is now better known as a hardy yellow rose that ages to white. This year’s list of new recruits is twined with roses that could overgrow their namesakes—in a few generations, we might squint at plaques commemorating country star Miranda Lambert, Freddie Mercury impersonator Joseph Lee Jackson, or manga character Aoi Tsuki.

Some roses, like this Savoy Hotel, are named after a famous old place instead. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

If a rose isn’t named for an objectively famous person, it’s likely named for someone more narrowly notable—the person who bred the rose, or someone that person loves. Charles Perkins, a grape and strawberry hawker who dabbled in plant breeding, named his first successful cultivar after his granddaughter, Dorothy. It sold so well that he ditched the fruit, and his company, Jackson & Perkins, became the country’s premiere rose producer (although they don’t breed Dorothy Perkinses anymore—too mildewy).

Bigger rose companies now trademark their cultivar names to prevent confusing repeats—sorry, Elizas of the world. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

When they run out of loved ones, some growers take requests. “When I started breeding roses I could never imagine the tragedies of people I would come into contact with,” says Robert Webster, who named one flower for a disgraced Marquess, and several for victims of murder, suicide, and cancer. “But I am pleased with the comfort, however small, I am able to offer from what I consider to just be a hobby.” His favorite rose—Betty’s Smile, a mildly scented light pink bloom—is named for his sister, who died of multiple sclerosis.

Rudolph Geschwind was a 19th century Austro-Hungarian rosarian. He named this creation, “Geschwind’s Schonste,” after himself—the name translates to “Geschwind’s Most Beautiful.” (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Some rose names make intuitive sense. Climbing Pinkie, for example, is pretty self-explanatory. It’s hard to look straight at Blushing Knock Out, and Buff Beauty is both handsome and delicate. “I always try to match a name with a rose,” says breeder Richard J. Anthony. One of his latest concoctions, Tattooed Daughter, “was named by my friend after his daughter who has numerous tattoos… The rose is striped and reminded him of his daughter’s arm.” Melanie Sifton’s current favorite is Gourmet Popcorn—”it just looks perfectly like it was named,” she says, with clusters of small yellow-white blossoms that seem recently burst.

Doesn’t this Lavaglut look like it just spilled out of a volcano? (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Others are more of a reach. “If you’re really into breeding plants, you’re going to have hundreds if not thousands of opportunities to name [them],” says Sifton. Combine that with pressure from various marketing departments, and some of those are bound to be kind of silly. Crafton has a bunch of roses with names that seem to come out of nowhere—”Shalom,” say, or “Freckles.”

“Sometimes a nurseryman wishes to obtain a rose for naming themselves, mainly to give a name that they believe is commercial,” says Webster—thus the pink behemoth Rose In Memory of My Cat, now sold all over Great Britain. Webster fears we’re forever past the days when “the public accepted that a good rose should have a good respectable name. Today most roses are sold because of the name… the quality of the rose seems immaterial. Sad but true.”

One of three different rose cultivars named Free Spirit. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Some roses will never bow to commercial pressures. Sifton, who is from Canada, says “there’s one that my family loves but Americans don’t know about—it’s a rose that commemorated the War of 1812, which the British and Canada won and America lost. So it’s not something that you hear about down here that much… they probably wouldn’t even bring it to market down here.”

In Canada, though, it sells out as soon as growers get it in stock. There’s something to be said for names with thorns.

American Pillar, ready to start another war of the roses. (Photo: Cara Giaimo)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook