How Santa Survived the Soviet Era

Of all the variations on the beloved character, Russia’s Ded Moroz might have the strangest history.

There are versions of the character widely known as Santa Claus throughout northern, central, and eastern Europe—all large, bearded men who arrive with winter to bring gifts to children. Russia is not exempt from this, but the Russian version, Ded Moroz, which translates roughly as “Grandfather Frost,” has a particularly strange, convoluted history.

Ded Moroz today is about what you would expect. He has a long white beard, wears a fur-lined hat, has an animal-towed sleigh, and delivers presents to well-behaved children when it is cold outside. But Ded Moroz’s last hundred years have been violent, political, and full of massive social upheaval. This, for Santa, you would not expect. As a result, his status is unlike that of any of his holiday peers around the world. For one thing, he isn’t even necessarily associated with Christmas.

Santa Claus is one of several manifestations of a particular wintertime character, probably originating with the pagan, pre-Christian Germanic and Norse god Odin. Odin was a fearsome bearded figure, rode a flying horse, and was often associated with the Christmas predecessor holiday Yuletide. In fact, one of Odin’s names translates as “Yule Father.” As Christianity swept through the colder parts of Europe, many Yule traditions became Christmas traditions, and Odin’s image blended with stories of Saint Nicholas, a fourth-century Greek bishop also known as Nicholas the Wonderworker for his many miracles.

From there the character evolved into distinct but similar forms. There’s Sinterklaas in the Netherlands, Joulupukki in Finland, Mikulás in Hungary, and several more. Over time some have faded away and shaded into the more international Santa Claus. Ded Moroz was the Russian form of the bearded wintertime gifter.

Christmas was a major holiday under the tsars, though not as important as Easter. It wasn’t really a festival exactly, but more of a somber religious holiday marked by fasting and long church services in Old Church Slavonic (which, by the 19th century, hardly anyone could understand). The Russian Empire of the 18th and 19th centuries was religiously diverse, but in most of what is now Russia and Belarus, if you were Christian, you were probably Eastern Orthodox. The Eastern Orthodox Church used, and sometimes still uses, a totally different calendar than the rest of the Russian Empire—the Julian one, which is 13 days behind the more common Gregorian calendar. This means that in Orthodox communities, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day celebrations would actually take place on January 6 and 7, out of step with the rest of the Christian world.

Ded Moroz emerged around the late 19th century. One of the first major cultural introductions of the character was in the 1873 play The Snow Maiden, by Alexander Ostrovsky, one of the most important playwrights in Russian history. Ostrovsky was often a political writer, and The Snow Maiden is an odd entry in his oeuvre. It’s a fairytale, based in part on obscure and largely forgotten pre-Christian pagan mythology, and designed to promote a different kind of Russian patriotism than the Imperial government’s brand. The play was published—not necessarily a given for Ostrovsky, who had many of his plays censored or banned—and eventually rewritten as an opera, which was performed many times.

The play included the notable characters of Snegurochka (the titular maiden) and her grandfather, Ded Moroz. He was based on a very old and mostly forgotten character in Russian mythology, an elemental snow demon. Demons of his breed aren’t necessarily bad guys. Ded Moroz was actually a good omen, because he was associated with particularly brutal winters, which, in Russian superstition, mean a good harvest the following year. By the time of Ostrovsky’s play, Ded Moroz and the other pagan demons were thousands of years old and had not had a place in the contemporary Russian Empire.

The educated classes loved The Snow Maiden, and interest in its characters, especially Snegurochka (who was created by Ostrovsky) and Ded Moroz, grew. “It was a development from the better-educated strata, in the cities, who were aware of how much joy the Santa Claus, tree, and presents gave to the kids,” says Vladimir Solonari, a historian at the University of Central Florida who was born and raised in Moldova. Suddenly there was a ready-made, deeply Russian version of Santa Claus, and the less-religious Christians began to use him in Christmas celebrations in essentially the same way that Santa Claus and his kin were used elsewhere.

He rewards good children with presents, and brings celebration and good tidings. He wears a big, fur-lined coat, though Ded Moroz’s is often an icy blue or patterned white, along with traditional felt valenki boots. He also carries a magical staff, though it’s not clear what he does with it. His flying sleigh is technically a troika, pulled by three horses, with no reindeer in sight. Ded Moroz is usually accompanied by Snegurochka, his granddaughter, and she is always dressed in white or very pale blue. She is sort of Ded Moroz’s helper, more of a partner than the elf-employees of Santa. He doesn’t live at the North Pole; a few northern sites lay claim to being is hometown.

The Eastern Orthodox Church wasn’t very into Ded Moroz, because he wasn’t a Christian figure, but was rather a resurrected pagan remnant who did not square with the stricter observance of Christmas. But by the early 20th century, his popularity and that of his granddaughter had grown. Then they faced a struggle that no other Santa Claus type has ever had to endure.

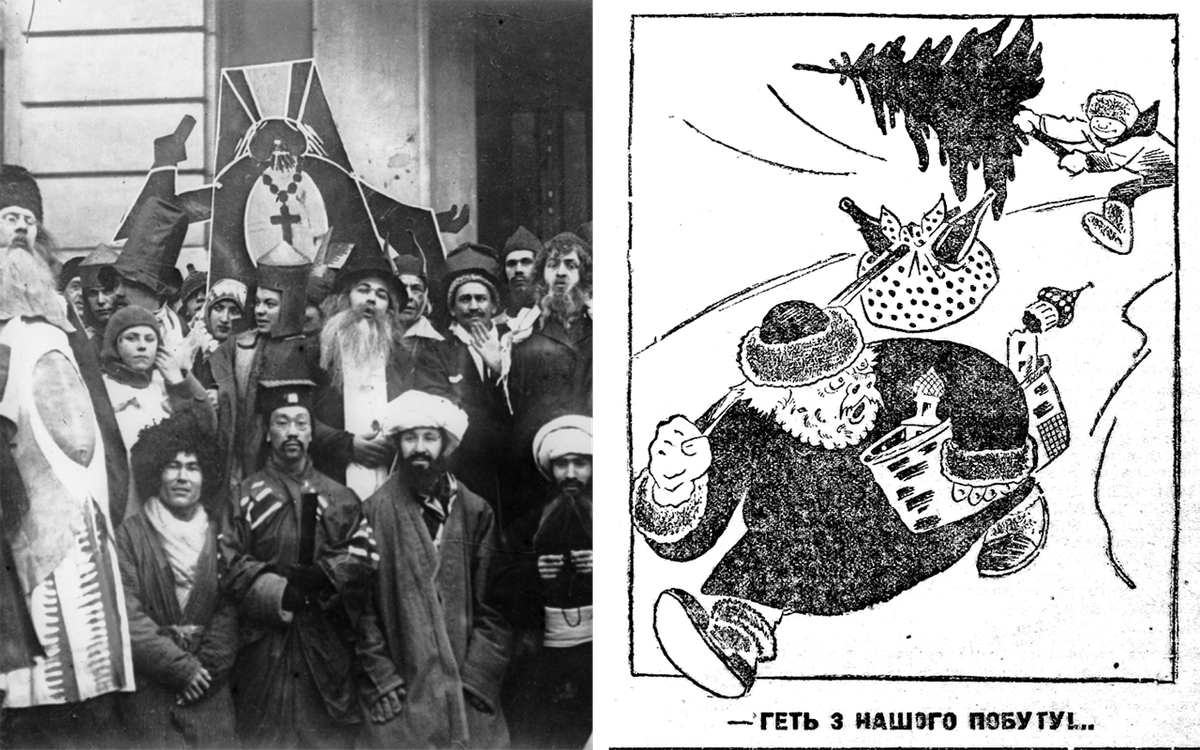

Among the stated goals of the Communist Revolution of 1917 was to abolish organized religion and establish atheism throughout the Soviet Union. “It was remarkably effective,” says Catherine Wanner, a historian and anthropologist at Penn State who works on religion in the Soviet Union. “I’m not certain they produced atheists, but they certainly got rid of overt religious celebrations.” Attacks against organized Christianity came in several brutal waves throughout Soviet history. Priests were thrown in camps or simply executed, churches were destroyed, and the ruling powers bombarded the country with pro-science—or, more accurately, anti-religious—propaganda. One example: There were patrols at one time that actually looked in windows for Christmas trees. If they saw one, that family was in serious trouble.

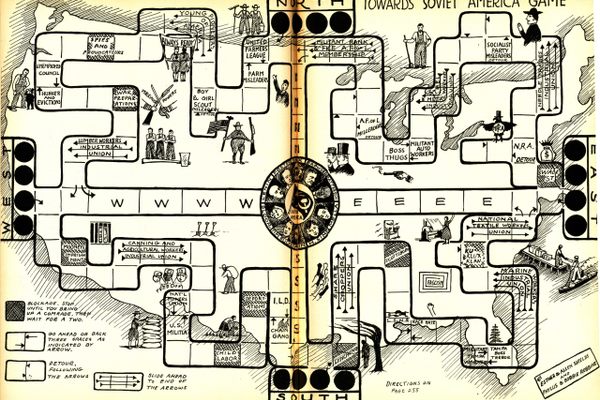

The brutality and singular focus of the attack on organized religion produced a culture, especially in the cities and larger towns, of complete terror at the idea of practicing religion. But, starting with a 1935 letter from a prominent Soviet politician, the idea of some kind of wintertime holiday began to take hold. By 1950, it had been firmly established. It was not Christmas, of course. The wintertime Soviet holiday would be “Novy God,” or “New Year.”

These holidays are treated separately in most places today, but in the Soviet Union, most of what had previously been associated with Christmas grew to become associated with Novy God. For the last four or five decades of the Soviet Union, everyone had a Novy God tree, and Ded Moroz made an appearance. It was not—for a while, at least—as consumerist as Christmas. It was more like Thanksgiving: national, secular, marked by feasting and family.

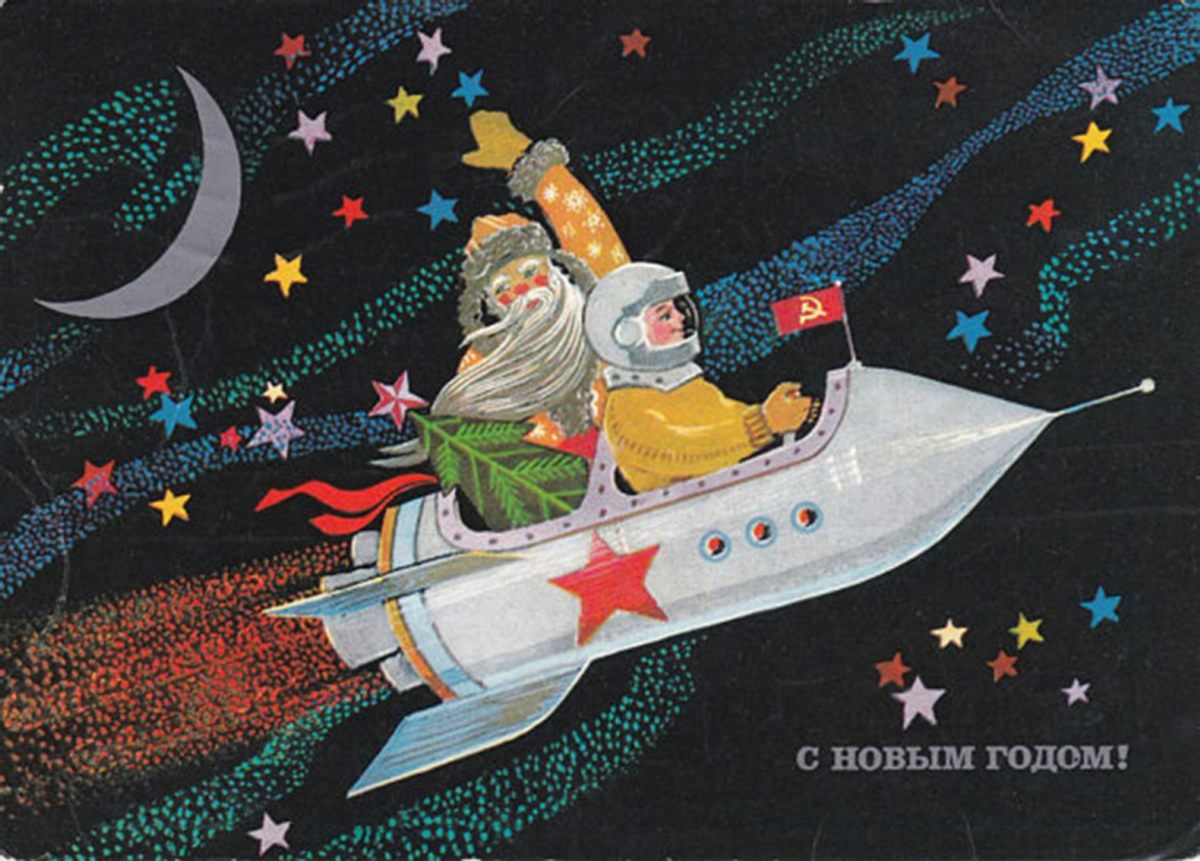

In this context, Ded Moroz’s pre-Christian roots were an asset. The Soviet leadership never said this explicitly, but it seems likely that they permitted and even encouraged Ded Moroz because he was, theoretically, Russian, born and bred. Depictions of Ded Moroz changed with the times during the Soviet era. For the Space Race, he was sometimes shown driving a spaceship rather than a troika. At other times he was depicted as a muscular, hard-working, semi-shirtless emblem of Communist industry.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, religious practice became legal again. But that put those who were theoretically Christian in a very weird position with regard to Christmas. They were able to celebrate Christmas, but they had never done it before. In fact, their parents, grandparents, and even great-grandparents had likely never celebrated Christmas. And Christianity in Russia still largely means the Eastern Orthodox Church, which carries its own complicated baggage.

The modern Russian government, which does not enjoy universal popularity in Russia, is heavily associated with the Eastern Orthodox Church. Not everyone finds it appealing to celebrate a holiday that’s supported by both the Church and the Putin government. “Actual attendance at church is very low in Russia,” says Wanner. “It’s not to say that religion isn’t important or that the Church isn’t important, but attendance is low.”

Today, Russia has what’s called a “holiday marathon.” It starts with the Gregorian calendar Christmas on December 25, passes through Novy God, which remains a much bigger holiday, and finishes with Christmas as it appears on the Julian calendar, on January 7. It’s sort of exhausting, but Novy God still stands out as the most important single date. Gift-giving largely happens then, and when you wish someone the tidings of the season, you say “С Новым Годом,” or “Happy New Year.”

“The vast majority of people living in these countries [Russia, Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine] still perceive the New Year as a much more important holiday than Christmas and most of those claiming to celebrate Christmas view it merely as an occasion to launch a party that usually lacks any religious content or even the sentimental sweetness typical of Christmas celebrations in the West,” says Alexander Statiev, a historian at the University of Waterloo who focuses on the Soviet Union.

Through it all, there is Ded Moroz and his granddaughter Snegurochka. They appear in seasonal cartoons, on greeting cards, in advertisements. People dress up as these characters for celebrations of various sorts. There are many classic Ded Moroz movies, which people watch every year, the equivalent of A Charlie Brown Christmas or Home Alone.

Ded Moroz is an unusual Santa-type for a bunch of reasons—his blue outfits, his traveling companion, his magical staff. But what’s most unusual about him is that he isn’t even really a Christmas figure at all. Happy New Year!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook