The Last Goatherd in Hell

Alfonso Hernández Saguero is preserving an ancient way of life and its cherished foods.

Every morning in the valley of Jerte, deep in Spain’s remote Extremadura region, 40-year-old Alfonso Hernández Saguero makes a pilgrimage to a lonely hilltop to keep a dying tradition alive.

Hernández arrives before dawn to unlock a low-slung stone barn partially built into the hillside. It’s January, with frost on the grass, but inside it’s almost cozy, thanks to the 200-some black, long-horned goats curled up sleeping. They are Veratas, a breed indigenous to Extremadura and now considered endangered.

Hernández grabs a bucket and starts milking. Many goat farmers use a milking table, a platform with feed boxes and restraints that keep goats from fleeing or kicking. But Hernández simply squats down behind each goat. The milk zings against the side of the bucket; the goats don’t kick or fuss. Maybe this is because Hernández is a fourth-generation goatherd, and some of these goats are descendants of the ones he began taking care of at such a young age that he can’t remember when he first started doing the work. “You could say I was born a goat,” he jokes.

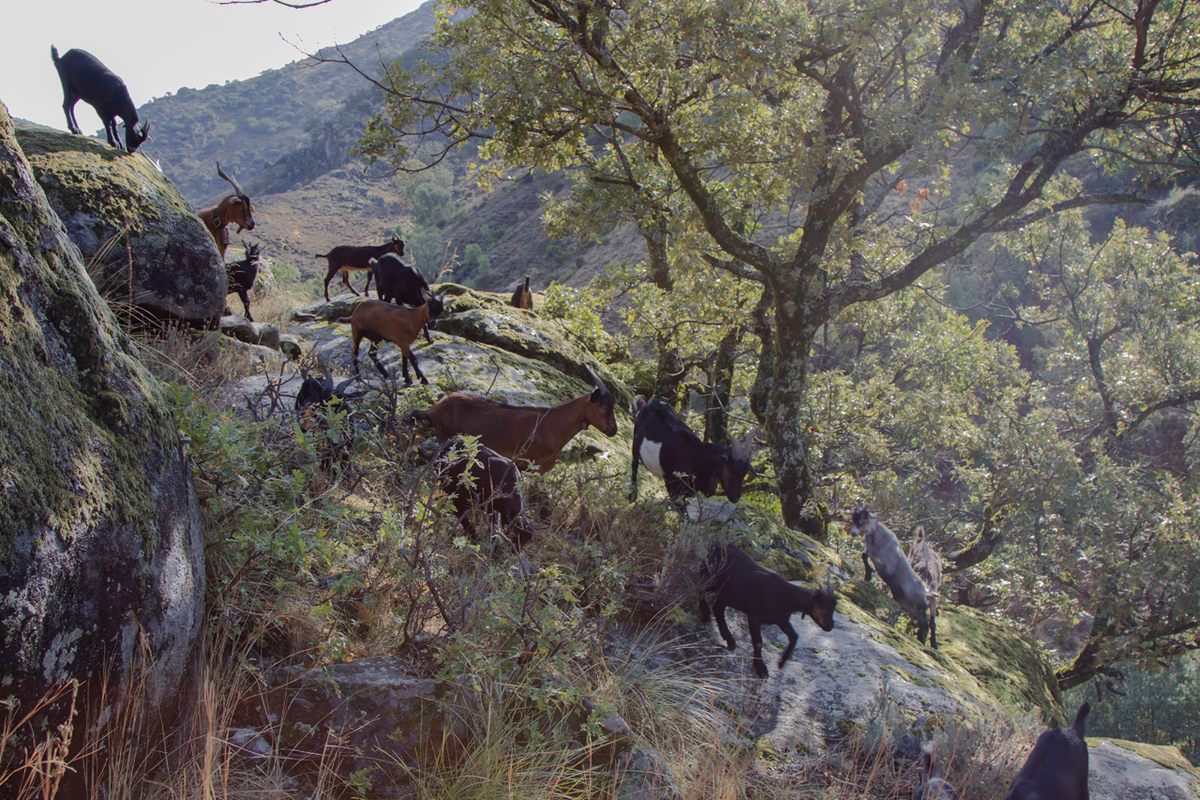

The milking finished, Hernández leads the Veratas out of the stable with a high-pitched whistle, two collie mixes barking eagerly at his side. The goats move along the barren mountainside, making do with what’s available in winter. They gobble up ivy, blackberry brambles, and cantueso, a wild herb that smells like lavender and rosemary. Hernández is relaxed but alert. “You have to go with your sixth sense in front of you,” he says, intuiting where the goats are headed next.

For thousands of years, this type of pastoreo extensivo, the grazing of goats on broad areas of wild land and pasture, has been a mainstay of rural life in Spain. It has left a deep mark on both national and Extremeño cuisine, from the wide variety of Spanish goat cheeses to the roast cabrito (kid) eaten at Christmas. But in the 21st century, traditional goatherds such as Hernández have become as endangered as his Veratas, even in Extremadura, where agriculture is still king. According to local records, from 1960 to 2019, the number of goats being raised in the Valley of Jerte dropped from 26,000 to 3,000.

As the sun rises, the landscape appears in all its eye-popping glory: the Garganta de los Infiernos (in English, the Gorge of Hell), a stunning natural reserve that draws more than 300,000 tourists each year. Most come in summer, to swim in Los Pilones, a series of crystalline natural pools carved in the river bed’s pale granite. On a winter day like this one, Hernández will be lucky to encounter the odd hiker. But when he was a child, about a dozen families led their herds each day along the steep slopes of the Gorge of Hell. “You even had to change your route so you wouldn’t run into another herd,” he says. “Here I am [now], and it’s just me. Because everyone else has disappeared.”

In a clearing even higher up than the barn, Hernández and his herd pass signs of this lost community—ruins of round stone huts which goatherds have built and lived in for centuries. But these are relics of a recent past, not an ancient one. Until he was a teenager, Hernández, his parents, and three siblings drove their goats over backroads and trails from the warmer dehesa, or pasturelands, farther south to spend summer and autumn in one of these chozos. His grandparents built it by laying flat stones to form a floor and arranging branches to make a conical roof. Every summer, the family added a new layer of piorno, a kind of brush, to keep out the rain. The single room served as living room, bedroom, and kitchen. The bathroom? “In the street,” Hernández jokes.

Under those thatched roofs, the Hernándezes and other goatherding families whipped up dishes now considered delicacies in Extremadura. They ate sopas canas, a “white-haired soup” based on goat milk thickened with breadcrumbs and flavored with pimenton de la Vera, a strong paprika that now enjoys the European Union’s Protected Designation of Origin status. For dessert, they fried egg-and-bread-crumb dumplings and cooked them in goat milk to make sapillos, or boiled rice with goat milk and orange peel to make arroz con leche.

For the main course, goatherding families made use of every part of the cabrito. When Hernández makes a stew with wine and local bay leaves, he uses his grandmother’s trick of finishing the broth with pureed liver. He stews the feet in sauce, or makes them with rice. His mother used to sauté the brains and add them to the quintessentially Spanish tortilla de patata. Hernández’s favorite way to eat brain: Slice the young goat in half down the middle, from head to tail, tie laurel leaves around each half of the skull to keep the brain inside, and make a stew. Even the intestines—thoroughly washed—are delicious. Hernández cooks them with salt and bay leaves, chops them up finely, and sautés them with onion, bell pepper, and the goat’s own blood. They’re known as chanfaina.

From his parents and grandparents, Hernández learned not only how to cook with goat milk and meat, but how to play the many roles required of a goatherd. In summer, when his goats give birth, Hernández is a midwife. He’s a veterinarian year round, fixing broken legs and saving overly curious baby goats whose heads are stuck between large boulders that dot the hillside. When the goats are tranquil, he sits on a boulder with a view of the gorge and carves new bell-clappers from Holm oak, using one of his grandfather’s clappers as a reference.

For a few years, he documented these adventures, along with his cooking, on Facebook. He ended up with more than 1,000 followers, and Jerteños still know him as El Cabrero del Infierno, or the Goatherd of Hell. But he gave up posting because he didn’t want to be on his phone. He wanted to be with his goats.

As the light fades, Hernández leads his Veratas back down the hill to the stone stable. When Hernández was a child, his parents made their own cheese, sometimes smeared with olive oil and pimenton, and aged in their chozo. Every week, the Gorge of Hell goatherds loaded up their horses and rode down to Jerte, the nearest village, to sell their cheese. Villagers who are old enough still reminisce about this weekly market day.

The thermoses of milk in Hernández’s Land Rover, on the other hand, are destined for a large cheesemaker in a nearby town. Due to modern sanitary regulations, Hernández says he can’t afford the facilities to make his own cheese. (Don’t even mention the paperwork.) He jokes that if he looked too closely at his profits from milk, he might give up the job. That’s why, he says, he’s the only one left in the Gorge of Hell.

“[Others] get tired of it, abandon it. They take other alternatives.”

Hernández himself has been tempted to leave. At 19, he spent nine months doing voluntary military service in Madrid, and then nine years working around Jerte in forestry and agriculture. As a teenager, he had resented the long, grueling days of herding, but his time away, he says, “proved that this is what I wanted.” At 28, he started his own herd. Yes, he works 365 days a year, in rain, sun, and snow, but, he says, “I’m more satisfied, more happy than I would be in any other place.”

Hernández is not the only one trying to save this lifestyle, its animals, and its foods. About an hour southeast of Jerte, in the town of Casar de Cáceres, a group of Extremeños is working to transmit the pastoral tradition to the next generation. Their goal is to keep young people from fleeing rural areas, and to save a local delicacy from disappearing.

“We have a grave problem of generational loss,” says Mariangeles Muriel, director of the Fundación Cooprado, which was started by the agricultural cooperative Nuestra Señora del Prado Casar de Cáceres. Shepherds and cattle ranchers are aging out of the business, she says, and, unlike Hernández, the next generations are choosing to leave for cities and easier work. Rural depopulation is a problem throughout Extremadura, Spain’s poorest region, but Casar de Cáceres has serious skin in this game. It’s home to the Torta del Casar, a Protected Designation of Origin cheese that can only be made with milk from local Merino or Entrefina sheep. Every Christmas, Spaniards from all over the country clean out the supply. Muriel says local sheep milk production already can’t keep up with demand for the delicacy, and without new shepherds to replace the older generation as they retire, Torta del Casar will disappear.

In 2016, the cooperative founded what they call a “Shepherd’s School,” a five-month program combining classroom time and fieldwork to teach students everything about raising cows, goats, or sheep, from genetics and reproduction to cheesemaking. Some students are urbanites coming back to the land, while others come from farming families, says Enrique Izquierdo, the school’s coordinator and the grandson of a cattle farmer. With 12 to 15 full-time students a year, the school has graduated 57 people, and 70 percent of them have entered the field. Hoping to modernize their techniques, local shepherds and cattle ranchers have also been attending class.

Izquierdo thinks the future for traditional goatherds such as Hernández is in forming cooperatives that can share the burdens of physical labor and bureaucracy.

“Under the umbrella of a cooperative, we can cover the needs of our business while also being able to attend to our families,” Izquierdo says. That means more free time and a better quality of life. He adds, “We can’t be in the field all day long like our grandparents were.”

“They could be right,” says Hernández about the advantages of cooperatives. In the past few years, there was talk of creating a cheesemaking cooperative in the valley, and he considered joining, although the plans never materialized.

But, as you might expect from someone who insists on carrying out a 10th-century practice in the 21st century, Hernández ends the conversation by affirming, “But independently, it can work, too.”

When a goat gives birth, she produces an extra-thick milk known as calostro, full of nutrients for her kid. If you live in Jerte and are on good terms with Hernández, then, when one of his Veratas gives birth, he might offer to make you a culinary treat. In a pot over a low flame, Hernández mixes calostro with regular goat milk and sugar, stirring constantly until the mixture is about to boil, at which point he takes it off the stove.

Hernández echoes Izquierdo when thinking about his own legacy. His 16-year-old daughter, Cristina, loves the outdoors and joins him with the herd on weekends. But he doesn’t want her to take over the family business. It’s too grueling, he says. “I’d like her to have a better quality of life than I have.”

After a moment, realizing how he’s contradicted himself, he adds, “I’m here because I want to be. I carry it here in my blood, and that’s that. I don’t care if it’s 365 days a year. Because if you really do a thing with love … ” He doesn’t finish the sentence.

Left to cool, the calostro will thicken into a pudding-like consistency that can only be described as spiritual. In one bite, you’ll swear you can taste the entire valley: the aromatic cantueso, the blackberry brambles, the hard-earned nourishment of winter.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook