The 19th-Century Freakout Over Steam-Powered Buses

A new vehicle on the streets of London caused quite the commotion—and some light sabotage.

In the 1830s, the transportation industry of the United Kingdom took a dramatic turn. Large, clunking, hissing steam-engined vehicles—which looked like a cross between a carriage and a trolley car—began to rumble along the roads. Alarmed by their appearance, some people threw rocks at them. Others wrote furious letters to the local government. Still others used stones to block the paths of traveling steam buses.

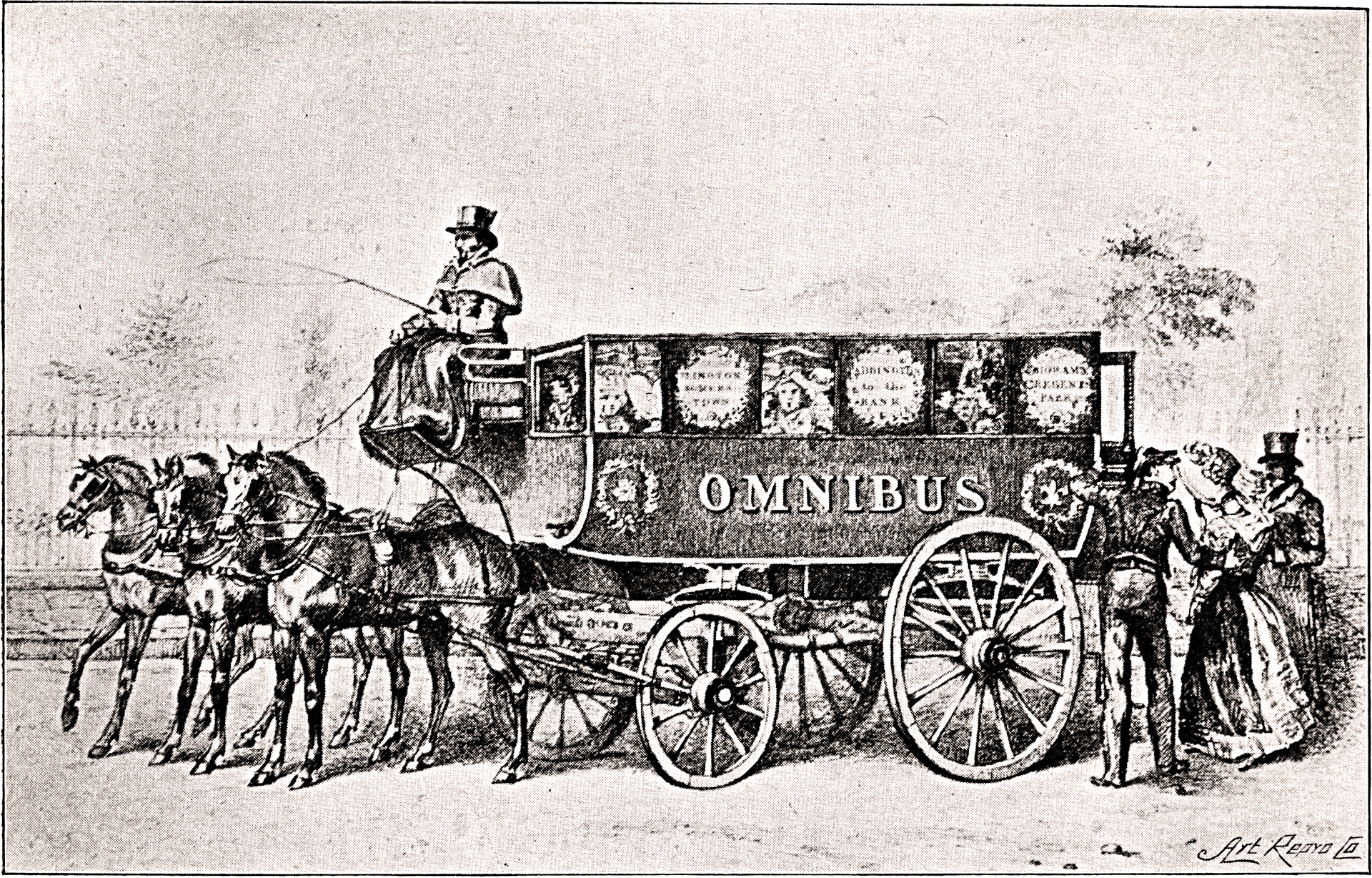

These salvos were part of a battle between old-fashioned horses and high-tech steam: horse-drawn omnibuses, from which we get our modern word “bus,” had been the public transportation standard, but now the steam-powered bus threatened to take their place. And that would not do. Horse-bus drivers and their supporters opposed the steam-powered bus technology so much that in the mid 1800s that they resorted to both legal and physical sabotage.

According to M.G. Lay in Ways of the World: A History of the World’s Roads and of the Vehicles that Used Them, while thousands of people in the U.K. welcomed and used the buses, which could hold over a dozen passengers at once, the enemies of the steam bus were fierce. Horse-bus drivers saw the new technology as a threat to their livelihood. Despite evidence to the contrary, many turnpike trusts, which managed roads between towns in the U.K., believed that steam buses caused more damage to the roads than horse’s hooves. The public nursed growing fears of the technology’s possible dangers: the machines were faster than any land vehicle before them, but steam power was seen as unreliable and a progenitor of explosions and accidents.

Various horse-drawn public transportation vehicles had existed in the U.K. since the 17th century, and while they were occasionally involved in accidents, they were a familiar technology. In the 19th century, with the invention of steam-powered engines, steam and horse-drawn buses were suddenly in direct competition for customers and the road. That competition got ugly relatively fast. Frederick Talbot wrote in his 1921 book on inventions that in one accident in Aldgate, England in the mid 1800s, a horse-drawn carriage and a steam bus resorted to a game of chicken when they “essayed to dispute the right-of-way,” causing an accident “with dire results.”

Omnibuses, which, like today’s buses, gathered travelers along predetermined routes, had previously competed with and triumphed over smaller horse-drawn stagecoaches, which required booking ahead. Now that horseless carriages were advertised to cause less damage to the roads, carry more people, and give a smoother ride than their horse-drawn counterparts, horse-drawn carriage companies had to double down their efforts to own the transport game.

The steam bus, a brand-new technology, encountered trouble on even slightly rough terrain. The steering was rough, and on early models drivers needed to stop and haul water from a nearby pond or stashed water source every six or seven miles to keep the steam going.

Accidents and mishaps added to a general public anxiety of the machines. Sir Goldsworth Gurney developed one form of steam-powered bus (often called “steam omnibuses”) which almost ran into a Bristol Mailcoach, causing Gurney to “force his vehicle into a pile of bricks” in front of a crowd, according to Dale Porter in The Life and Times of Goldsworthy Gurney. Gurney tested his vehicles until he thought they were safe, but steam power’s reputation began to fall into ruin almost from the start, as seen in poet Thomas Hood’s take on the new tech:

“Instead of journeys people now go up on a Gurney

with steam to do the work by power of attorney

but with a load it makes blowed and you all may be undone

and find you’re going up to heaven instead of up to London”

Evidence of the steam-bus’s dangers mounted as the technology was refined. In 1833, a vehicle owned by bus company entrepreneur Walter Hancock appeared in headlines after its engine exploded during an en-route repair performed by the bus driver, which ended in the driver’s death.

Advances continued despite public fears, and bus lines began to grow in London by the mid-1800s. One of Hancock’s steam buses, the Automaton, could carry an unprecedented 22 people; vehicles of his brought travelers around London and into other towns, and sported names like Autopsy, Infant, Enterprise and German Drag. In the book Birth of the British Motor Car, T. R. Nicholson writes that the steam bus was heralded by the press at times, with one source insisting that “scientific and practical men of all ranks” understood steam-powered buses needed to replace horses as a more efficient transportation of the future.

Horse-drawn companies became especially wary of Gurney’s threat to their livelihoods, according to the Local Transport History Society in the U.K. Starting June 23, 1831, stagecoach drivers decided to sabotage his vehicle. The saboteurs laid deep piles of stones onto the roads in front of one of his steam carriages three days in a row, damaging the machine and causing it to topple over.

The scale tipped further out of the steam bus’ favor with laws supported by Parliament’s House of Lords, who may have been influenced by angry horse-carriage investors and citizens. New Turnpike Acts instated harsh tolls on steam-powered or motorized buses, and England’s Locomotive Act of 1861 (known also as the Red Flag Act) required self-propelled vehicles to be led by a man who carried a red flag, to make sure the speed was limited to walking pace. At one hearing, Gurney said “wherever we attempted to run, or contracts were made, we were met by an act of Parliament.”

Steam powered buses did try to compete into the late 1800s and early 1900s, until gas-powered cars closed in on the industry in the 1920s. In the end, motorized buses won, and no one baulks at the idea of a heavy, metal contraption zooming travelers about town.

Of course, new forms of transportation may still be regarded with suspicion—the advent of self-driving cars has drawn similar fears to those of the steam-bus era. Maybe we’re bound to relive another round of condemnation, but this time, at least, let’s hope saboteurs stay out of it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook