Misery Doesn’t Seem to Improve the Quality of Art

Under scrutiny, the image of the tortured genius appears to fall apart.

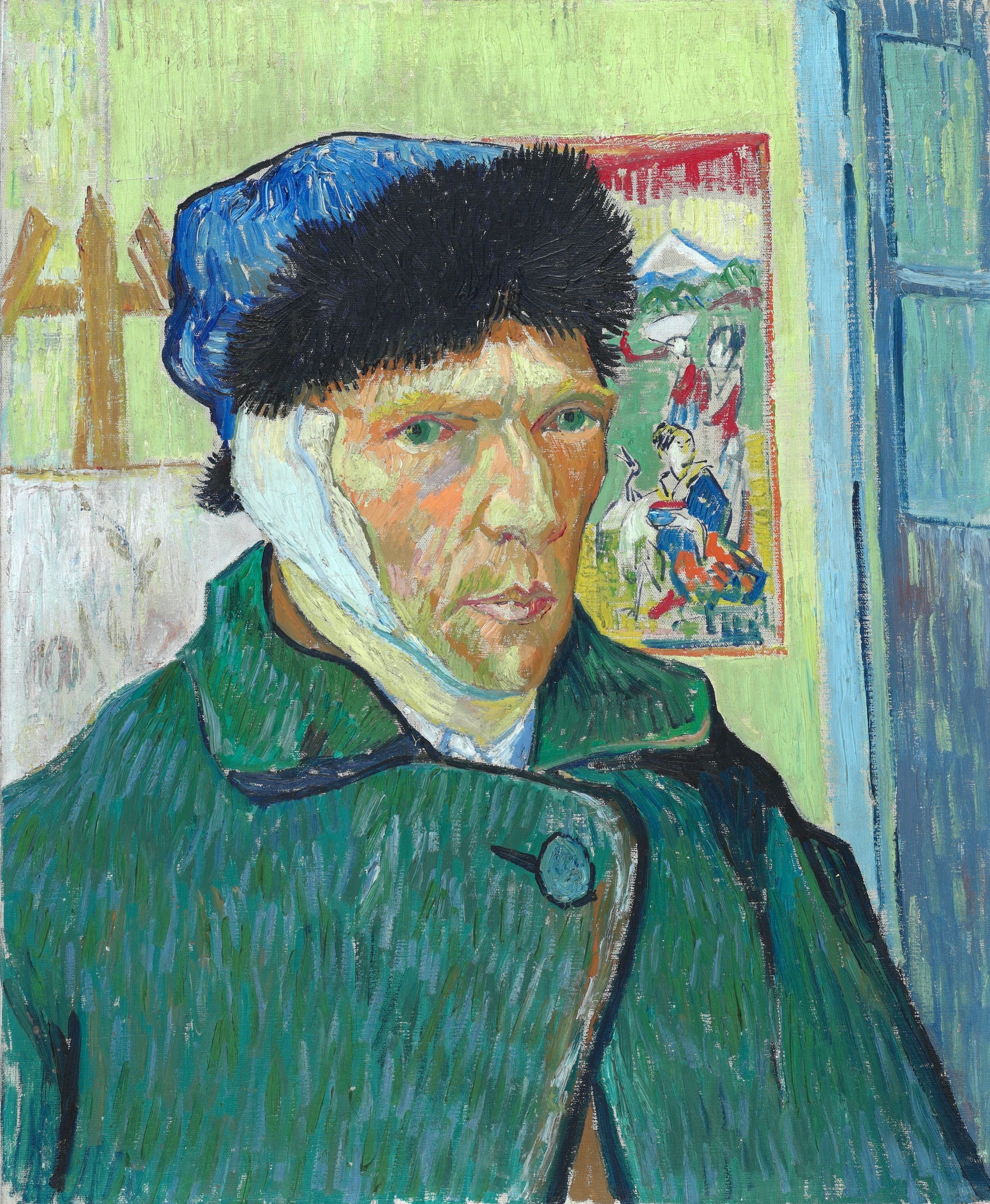

After Pablo Picasso’s friend Carlos Casagemas committed suicide in a Paris cafe, for three years the artist painted only in shades of blue and blue-green. Amid deafness, isolation, and intense anxiety at the end of his life, Francisco Goya covered the walls of his home with harrowing images of death, dogs, and devastation. Before his suicide, Mark Rothko abandoned bright colors for blacks, burgundy, deep green, and other melancholy shades. And in 1888, the year Vincent van Gogh cut off his ear, he produced dozens of extraordinary paintings, including his famous Arles work. Sometimes, it seems, despair nourishes art. But a new study released this week in the journal Management Science begs to differ.

Researchers Kathryn Graddy and Carl Lieberman compared the sale prices of some 15,000 paintings, using the Blouin Art Sales Index and the online collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Musée d’Orsay. Some of the works coincided with happy periods in artists’ lives, and others with times of misery or grief, such as following the death of a friend, lover, or relative. A hue of angst and despair might make work more interesting—the jury’s out on that—but it doesn’t make it more valuable. In fact, work created during what the researchers call “a period of bereavement” was up to 35 percent less valuable than a given artist’s other pieces. On top of that, the morose works were less likely to be included in the collections of major museums.

Grief and depression are hard, exhausting, and often monotonous—and this new analysis also suggests that they can actually stifle creativity. In a statement, Graddy said: “Our analysis reflects that artists, in the year following the death of a friend or relative, are on average less creative than at other times in their lives.” Take Claude Monet, for instance. In 1867, when he was 27, his mother died. Four years later, his father followed. In 1879, he lost his first wife, Camille, and in 1911, his second wife, Alice, and oldest son, Jean. Not a single one of his top 10 most valuable paintings were painted in, or even close to, these difficult years.

Other studies have shown that firm performance declines if a CEO loses a family member, while the death of an executive is bad news for shareholder value. Even simple numerical tasks are harder to do in the wake of the death or illness of a relative. If, as famed graphic designer Milton Glaser said, “art is work,” it is perhaps no surprise that it suffers when you’re too miserable to concentrate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook