The Surprising, Overlooked Artistry of Fruit Stickers

Kelly Angood curates an online museum of little, adhesive marvels.

Some of the world’s best, most surprising graphic design can be found in one of the most mundane places: your local supermarket. Nestled among pyramids of plums and bagged bunches of bananas are tiny works of art. Welcome to the world of fruit stickers. In much of the world, especially in large American supermarkets and chain stores such as Walmart, the stickers simply advertise somewhat ubiquitous brands—think Chiquita or Dole. But in the United Kingdom (and other places), smaller greengrocers carry produce plastered with tiny, hyperlocal stickers that bear the logos and art of smaller farms, growers, and distributors. When most people encounter these stickers, it’s only to peel them off and try, often unsuccessfully, to flick them into the trash. But Kelly Angood sees something else in them, and peels them carefully off before adding them to her collection of hundreds—spanning countries, decades, and a dizzying variety of fruit.

Angood, who works as a graphic designer in London, started collecting fruit stickers in the 1990s, on sort of a whim. She stuck the stickers all over when she found them, on the backs of notebooks or on whatever flat item she happened to have on her. As the years passed, her collection sprawled. She began putting her finds neatly on white printer paper, dozens of stickers per sheet, and soon had enough that she decided to start posting the best on Instagram. @Fruit_stickers hosts a beautifully curated selection of close-ups. She frames each against a flat white background, more like an art gallery than where you might encounter these easily overlooked marvels of design in the wild.

The first person to put stickers on fruit on a commercial scale was Tom Mathison, a produce farmer in Washington, according to his obituary in Produce Processing, an industry trade magazine. He put stickers on his apples to brand them with the name of his farm, and eventually added a ladybug logo to signal their organic origin. He saw them as a potential marketing strategy for grocers and growers, as a way to communicate the quality of a piece of fruit. “You’ve got a banana, an apple, an orange. As a consumer, how are you supposed to tell the difference from one to another?” Angood says. “The only way is a tiny sticker that is associated with being a sign of quality and consistency within that grower.”

Now, produce stickers—not just for fruit any more—are commonplace worldwide. In several countries, they are highly regulated to help supermarkets control inventory and consumers learn more about their choices. This regulation exists in the form of numbered PLU codes, set by the International Federation of Produce Standards. Growers use PLU codes in the United Kingdom, the United States, Chile, Canada, Australia, Norway, and New Zealand, under the same standard set of rules. If a PLU code begins with a 9, for example, the fruit is organically grown. If it begins with a 48 or 49, it indicates herbs. The codes make for a more seamless shopping experience, but they occupy valuable real estate that could have otherwise gone toward design. As a result, the most aesthetically appealing fruit stickers, Angood explains, are often the ones that come from the least regulated places. But while the PLU system governs stickers within the countries that use it, fruit moves elsewhere around the world in more wanton ways, so produce sections anywhere can carry purely decorative stickers or fruit that goes completely sticker-less.

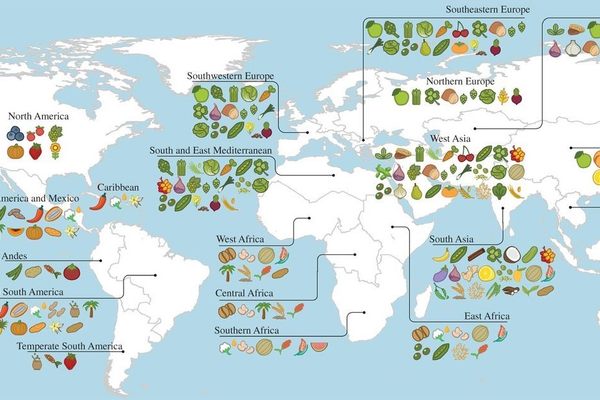

Angood’s collection is dominated by fruit you can buy for sale in London—which is to say, the stickers come from all over the world, since very few exciting fruits grow naturally in Britain. She picks up any stickers that catch her eye aesthetically, perhaps with an unusual color combination or flashy typography. She rarely actually buys the fruit attached to the sticker, but she says vendors never seem to mind, as one stickerless fruit has little effect on the store’s ability to sell produce. “I lived next to a greengrocer, and they knew the score,” Angood says. “It’s more awkward to ask.” She has never managed to successfully trace the designer of any of sticker she’s collected, but then again, there are probably an awful lot of them.

In the world of fruit stickers, according to Angood, citrus is one of the best canvases. Her favorites are the green stickers she finds often on tangerines while on vacation in Valencia, Spain, that resemble the fruit’s leaves. “It’s almost alluding to its natural state,” Angood says, adding that the stickers typically bear the grower’s name on the leaf. She finds these more memorable, almost because they take the unusual advertising tack of trying to blend in.

Other stickers are arguably less artistic and certainly less subtle. Take the banana, in Angood’s experience the fruit most frequently anthropomorphized in advertising, including on stickers. Most ubiquitous is Dole’s human-banana mascot Bobby Banana—often spotted on stickers leading an active lifestyle that includes soccer or basketball. Del Monte takes a similar tack, with a similarly anthropomorphized banana that loves volleyball, cycling, and open mics. The company also launched a series called “Bananimals,” which consisted of animals with various body parts replaced by bananas. (You can probably imagine the Bananapus.) All of them appear on stickers, and Angood has most of them. “The Dole Bananimals … a lot of them are very phallic,” she says. “I’m like, ‘Why have you got a penis for your hands?’ It’s obviously supposed to be a banana, but it’s really quite ridiculous.”

Angood has noticed other, more inscrutable regional trends that she can’t quite explain. Many of the stickers she’s collected from growers in South America, for example, feature the image of a young child, likely from the grower’s family. “They take a picture of their youngest child and put it on fruit,” Angood says. “One time I saw one that wasn’t a child but a family dog.” In another strange trend, some growers mimic the design of a well-known brand to draw attention, such as a rip-off Rolex logo used on bananas in the Philippines. Angood’s isn’t the only Instagram out there that chronicles the surprising artistry of fruit packaging. Australian artist Sean Rafferty runs @cartonographer, dedicated to the cardboard crates used for fruit and vegetables in Australia. In a recent exhibition in Sydney, Rafferty lined up his vast collection of boxes according to the latitude of origin of their former fruit inhabitants, creating a graphical, botanical map of Australia.

Two decades into her collecting, Angood has learned that several of the growers whose stickers she saved have since gone out of business. And as her Instagram presence grows, people have begun sending her stickers of their own so she can post them. An American woman sent Angood a collection of stickers from the 1960s through the 1980s. Now, Angood can’t help but spot the stickers wherever she goes. “I have my eyes peeled constantly,” she says. “I can spot a fruit sticker on the street. It’s become part of the way I live my life.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook