In Sydney, Intricate New Models Depict Australia’s Brutal Colonial Era

A redesigned museum hopes to grapple with the thorny legacy of the “convict period.”

Somewhere in Darug Country, Australia, much of which is now greater Sydney, a forest is under attack. A path cuts through the densely wooded area like a scar, and freshly felled trees wait to be loaded onto a wagon nearby. A group of incarcerated men scrape and hack at the remaining trunks. Beyond the grove, at a distance, a group of Aboriginal Darug men watch, helpless. The scene is a microcosm of the island’s colonial period—literally. You will probably have to squint to see it all.

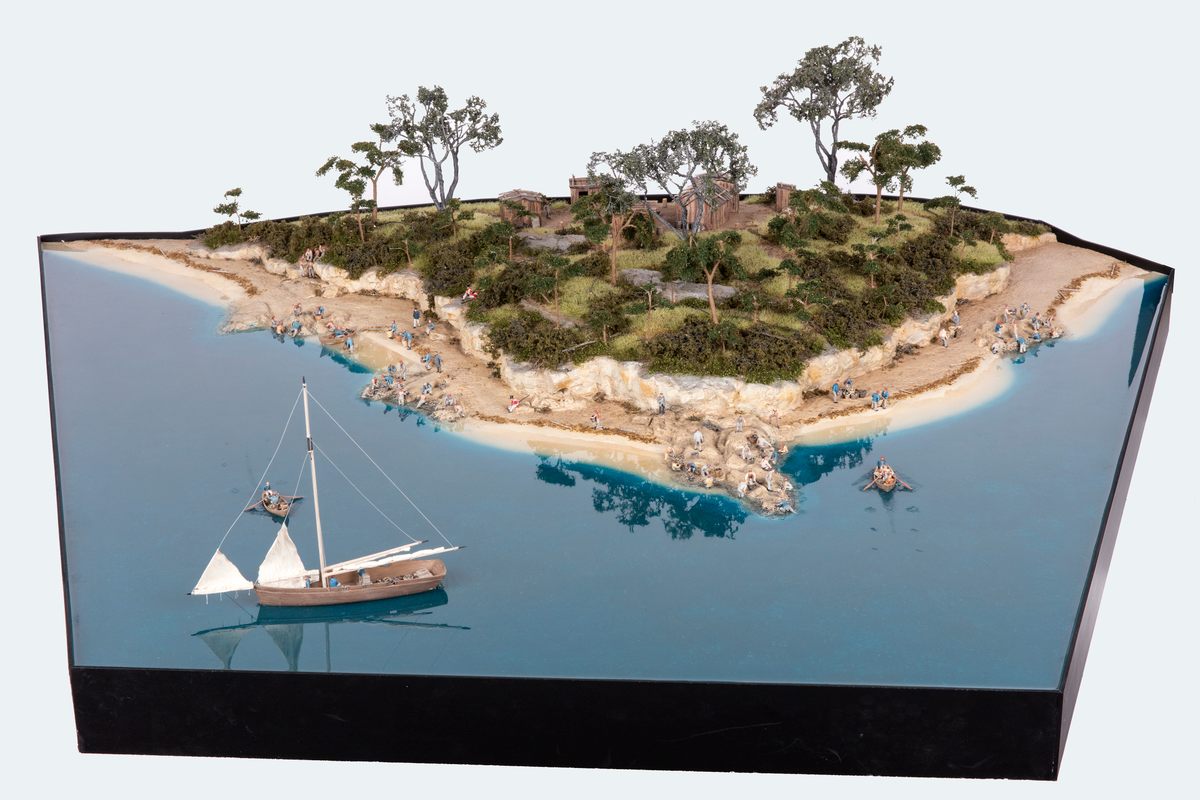

“Timber-Getters” is a miniature model of Australia’s history, at 1:100 scale, one of nine scenes built for the newly redesigned Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney. The historic compound opened in 1819 to house incarcerated men during Australia’s “convict period,” and is now managed by Sydney Living Museums (SLM). This makeover, two years in the making and wrapping up in February 2020, is meant to communicate a fuller, more inclusive history of the early colonization of Sydney, including its impact on Aboriginal people; the barracks themselves are built on traditional Gadigal land. For all their modern perspective, the models are charmingly retro. “That model [“Timber-Getters”] alone gets across the story of the colonial process and the devastation it wreaks on the country and its people,” says Gary Crockett, a curator at SLM. “Sometimes something cartoonish can capture a really large issue and boil it down into something that is immediately graspable.”

Britain began banishing its imprisoned people overseas in the early 17th century, primarily to the North American colonies. The infractions involved were largely petty affairs, as more serious crimes were punishable by death. The Revolutionary War shifted the focus to New South Wales, Australia, in 1788. In the early years, the sentenced people were not imprisoned exactly, but were forced to do labor for much of the day. “They worked until three or four in the afternoon and then were free to do their own work,” Crockett says. “In the early years, that level of freedom was quite extraordinary.”

But that changed when British officer Lachlan Macquarie commissioned incarcerated architect Francis Greenway to design barracks for 600 men, in the hope that living there would improve their moral character. (Macquarie was so impressed with Greenway’s work that he pardoned him.) “The barracks were all about control,” Crockett says. “It was a system of difficulty, punishment, and cruelty.” The barracks opened in 1819, and were copied in other British penal colonies.

The system was even crueler to the local Aboriginal people, thanks in part to the incarcerated labor force. “Convicts were at the forefront of growth and expansion of an ever-moving frontier—clearing lands, building roads and settling new farms,” Peter White, a Gamilaroi Murri man and the former head of indigenous strategy and engagement at SLM, writes on the museum site. “They played a pivotal role in the subjugation of the country and the many nations of people who were connected to that country.”

Condensing all this history into plastic models—comprehensible at a glance—was a dizzying task. Crockett and a team of SLM curators selected the nine scenes—five from the laborers’ perspective and four from an Aboriginal perspective. “We wanted to speak to the impacts that forced labor had not just on the colony, but what it meant for these Aboriginal communities who were on the receiving end of wave after wave of convict labor,” says Beth Hise, the head of content and strategic projects at SLM. “It’s an interesting process. It included everything from what size and shape should a wheelbarrow be, to how do we depict a cultural landscape and what do we need to include in it?”

Crockett and other curators prepared briefs for each scene, drawing on historical images and texts, then artists from Sydney Modelcraft took over. They consulted more historical images and descriptions, and carved each landscape out of foam, Matt Scott, director of Modelcraft, writes in an email. For one scene that depicts oyster collecting in Sydney Harbour, at a site that exists today, the modelers used modern photos and satellite views.

Then came the buildings, wildlife, trees, shrubs, trains, ladders, and wheelbarrows. For the people, they used commercially available figurines, such as those used in model train sets, and hand-painted them. “The whole thing had to be choreographed like a giant opera,” Crockett say. “Every character had to be plausibly different, from the tree cutter on the stone by the lighthouse, to the cook, to the boy running with the bucket of water, to the lazy soldier.”

Crockett wanted each scene to tell a story. For example, the oyster-gathering scene depicts how many of Sydney’s early buildings were built using ground-up shells as mortar. “We couldn’t just put 60 convicts on the beach,” he says. Instead, the figures were arranged in small scenes at each stage of the process: plucking the oysters from the rock, loading them into baskets, and preparing to load them to a ship offshore. The often-brutal reality of incarcerated life also makes appearances. One scene, which depicts a stone quarry labor gang, features an incarcerated man crushed to death under a boulder, and another bleeding and unconscious.

Developing the scenes spotlighting the Aboriginal experience was a lengthier, more complex process. The content of these scenes grew out the curators’ conversations with indigenous communities and consultants, which took more than a year. An Aboriginal curator joined the museum’s team on contract to assist. “We worked in equal partnership with Aboriginal communities,” Hise says. “And we ended up with a blended interpretation combining both historic record and cultural knowledge from the community.”

The four Aboriginal scenes, which all take place in Darug Country, depict the tree-clearing; the Blacktown Native Institution Site, a residential school for Aboriginal children; a peaceful Aboriginal community that is being ambushed by white settlers with swords; and a group of warriors led by the Wiradjuri resistance leader Windradyne attacking a settlement of incarcerated laborers. “It represents a retelling of these stories from an indigenous perspective rather than a curated colonial approach,” Scott says, adding that certain stories were removed from the models after the Aboriginal community deemed them to be inaccurate. More violent interactions—such as the massacre at Myall Creek Station, in which dozens of Aboriginal people were murdered by a white vigilante group, including laborers from the Hyde Park Barracks—are not depicted in the models.

For the tree-clearing scene, Aboriginal consultants arranged the trees and creeks certain ways and recommended models of specific animals that hold cultural importance, such as possums in hollow-bearing trees, Hise says. “A possum is so tiny at 1:100 scale but it’s incredibly important that we include them to convey what is happening when trees are torn down,” she says. “It’s not just a loss of trees, but a loss of animals and their homes.”

While the white laborers could be easily fashioned out of existing figurines, there were no existing models for Aboriginal people. Museum curators collected historic photographs and imagery in partnership with the Aboriginal community and asked an artist to 3D print original models, each under an inch tall. The model-makers consulted Aboriginal elders to get the right body shape, type, and skin tone. “It was amazing to see how an accurate 3D representation could be made from a single grainy historical photograph,” Scott says.

When the Hyde Park Barracks reopen on February 21, 2020, the models will each be displayed within a black structure with openings through which visitors can peek, Hise says. “It’s combined with an audio experience with the voices of people and characters from the past who introduce you to their world as they lived it,” she says.

Though the models tell a grand story at a small scale, each contains details that reward the careful viewer. “A visitor will have fun trying to find several birds in the trees of the native forest,” Scott says, kangaroos, long-necked turtles, and even fish. “I have it from a reliable source that there are three snakes to be found on every model.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook