How a Tiny Indian Publisher Brings a World of Comics to Tamil Readers

A four-person team translates Italian, French, and English comics into a language spoken by 70 million people.

The town of Sivakasi, near the southern tip of India, is known as a firecracker- and matchbox-making hub. Located more than 300 miles inland from the state capital of Chennai, Sivakasi is not a particularly literary place. But printing presses are a big part of the local economy, and with their help, the town has become an unexpected comic-book capital of India.

Half a century ago, a man named M. Soundrapandian completed an apprenticeship with a company that printed Chandamama, a children’s magazine that was published for 60 years in 13 languages. His native language was Tamil, the official language in the state of Tamil Nadu. More than 70 million people speak it, making it even more widespread than Italian, but many popular international comics were not being translated.

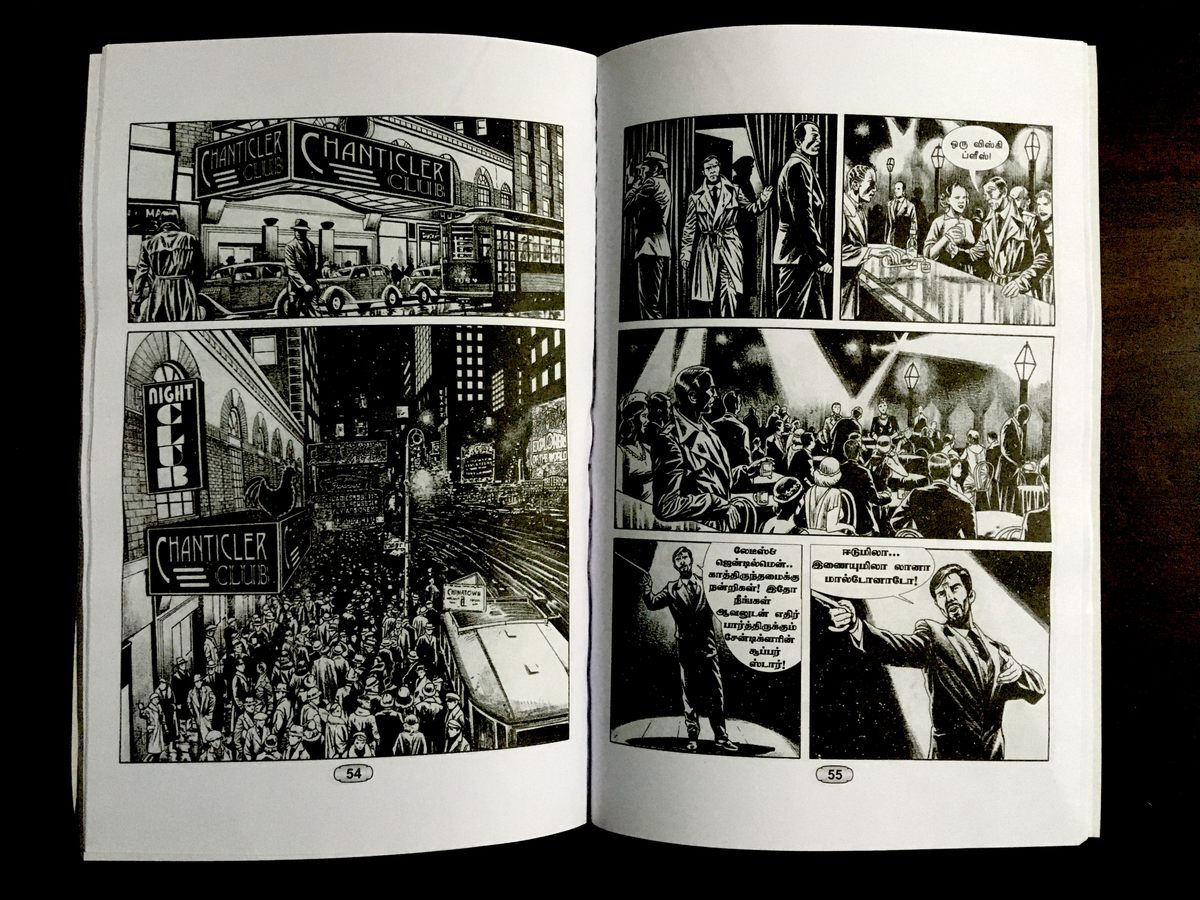

In 1972, Soundrapandian embarked on his first translation: Irumbakai Mayavi, or The Steel Claw, a popular weekly comic from the U.K. As it turned out, Tamil readers loved the adventures of a crime-fighting hero who loses his hand in a laboratory accident and gets a steel prosthetic. At the time, Indian comics were generally published in a single panel, and occasionally they occupied one or two pages in children’s magazines. Muthu Comics, as it was known at the time, was among the first Indian publishers to release a full-length comic book.

About a decade later, Soundrapadian’s son, Vijayan, took over operations. He was barely out of school, but he was able to ride the comics wave that crested during the 1980s. He traveled to the Frankfurt Book Fair and had a lucky meeting with big publishers from France, Italy, and elsewhere, he recalls, and they were “fascinated that a huge country like India would actually be interested in trying out their comics.” (Of course, he adds, the mass popularity of comics in Europe and their small-market appeal in India were as different as chalk and cheese.)

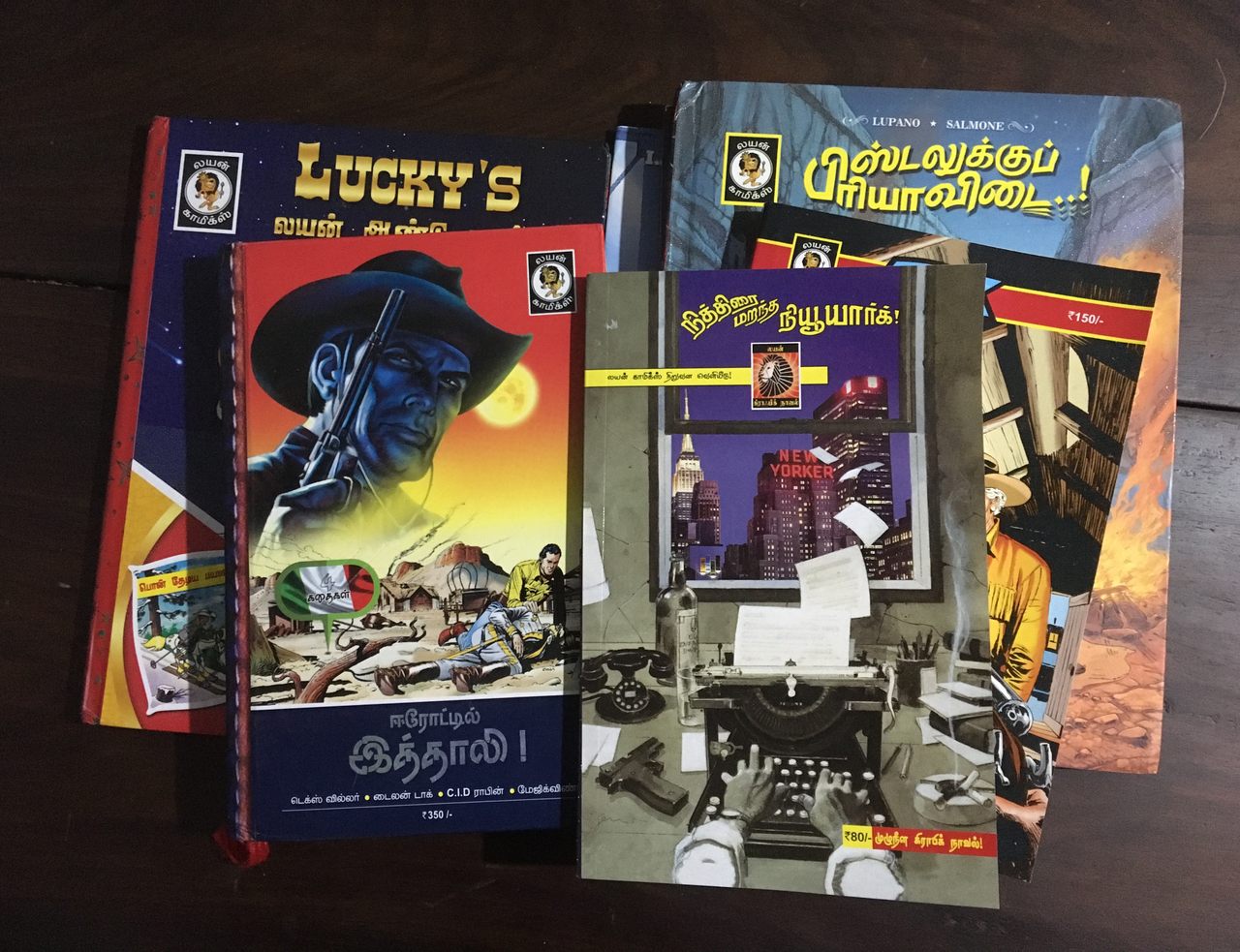

In the 1990s, India’s economy was liberalizing, but Indian stores tended to sell mostly superhero comics, such as Superman and Batman, as well as classics such as Tintin and Asterix. Even these were expensive and thus restricted to largely urban, English-speaking audiences. By translating beautifully illustrated comics into a language that was so widely spoken, and packaging them into affordable editions, Vijayan tapped into a new market.

Initially, Muthu published in black and white and priced its comics at around 3 to 5 rupees, or a few cents each. Only about a decade ago did the company, which is now called Lion-Muthu Comics, took its present shape. While the comics were initially sold at newsstands and through sales agents, Vijayan introduced a subscription model to reach his readers directly. Book fairs, which he says are very popular in Tamil Nadu, are another way to boost sales and build a relationship with his readers.

Vijayan’s translation team includes four people: a native speaker of Italian, a non-native speaker of French, Vijayan himself, and an old friend of his father’s, a native Tamil speaker. The first two translate Italian and French comics into English, and then Vijayan and his father’s friend translate them into Tamil. (The friend translates the straightforward stories into Tamil, while Vijayan takes on the harder subjects that need research and context for an Indian audience.) Vijayan says that subtleties are bound to be missed in the process of working between all these languages, but he likes to think that as a comics reader himself, he is mostly able to meet his readers’ expectations.

An elderly woman in Tamil Nadu, who prefers to remain unnamed, has served as Lion-Muthu’s French-to-English translator for two decades. She says that she grew up reading Tarzan and Archie comics, so she considers herself “very familiar with the language of comics.” She got the job by answering a small ad the publishers had placed. “A lot of the cowboys and detective stories are easy, I’ve done so many of them,” she says. Others require more research: “The French comics use a lot of curse words and slang, so one has to know those. You have to get into the mind of the writer to read between the lines.” When translating comics, she adds, “the language into which you are translating should be your strongest.”

Lion-Muthu Comics has fostered a reading community that could well be the envy of bigger publishing companies. Vijayan’s blog posts, which preview upcoming titles or share the backstory for a particular book, often attract hundreds of comments in the few minutes after they are published. These conversations continue offline at the Erode Book Fair every August. “People have flown in especially for this from the U.S.,” Vijayan says, incredulous. “Can you believe it?” He says the two-day affair is almost as festive as a wedding.

Today, the catalogue is a mix of titles for children, commercial comics, and genres such as cowboy and detective series. There is Pistolukku Piriyavidai, or The Gentleman Who Did Not Like Guns) about the debate surrounding the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, and Thanithiru Thanithiru, or Old Pa Anderson, about Black lives in 1950s Mississippi. Sippaayin Suvadagal, or Les Oublies d’Annam, depicts the horrors of the Vietnam War and its aftermath. “Almost 70 percent of what we do is not available in English,” Vijayan says.

Lion-Muthu Comics continues to keep the prices low, to compete with online booksellers. Comic books are priced at about 80 rupees, or a little over a dollar, while a graphic novel can cost four to five times that. “The readership is a very small circle now, I can’t afford to let it get any smaller,” Vijayan says. The company publishes about 55 translations a year, with a print run of 1,500 for each title.

In India, Vijayan says, comics are still seen as children’s books: They are sometimes called bombe-book, or “doll books.” It doesn’t help that many young people now do their reading online. But he gets satisfaction from the engagement with his community, and in bringing to Tamil the books he himself has enjoyed reading. In two years, Lion-Muthu will turn 50 years old. The company has survived long enough to serve generations of readers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook