The 100-Year History of Women Going Topless in Times Square

Sherry Britton during her act at the Minsky Gayety Folliesin 1940. (Photo: Bettmann/Corbis /AP Image)

Sherry Britton during her act at the Minsky Gayety Folliesin 1940. (Photo: Bettmann/Corbis /AP Image)

First it was a group of patriotically painted topless women (called desnudas) in Times Square, taking photos with tourists for tips this summer. Then it was a pledge by New York City mayor Bill de Blasio to create a task force to address “the growing problem” of “topless individuals” in the neon-lit tourist hub.

Shortly thereafter, hundreds of women took off their tops and paraded down Broadway, to prove that if men can go topless in public areas, so can women—it’s been legal since 1992. Now a full-fledged movement for the right to bare breasts is gaining steam in a place with a long history of naked ambition.

From the accidental invention of the striptease to the modern-day desnudas, here are the milestones in Times Square’s skin-baring story.

(Photo: Steven Pisano/flickr)

(Photo: Steven Pisano/flickr)

Circa 1915: The First Striptease

Rumor surrounds the invention of the striptease. Legend holds that an unidentified chorus girl “forgot” to don the starched collar and cuffs belonging to her dancing costume one night, resulting in a scandalous exposure of the neck and wrists.

In another version of the tale, an actress named Hinda Wassau discovered that a strap of her dress had broken as she was singing her big finale, and she decided to bare it all rather than dash offstage in the middle of the number. Yet another account claims that an anonymous dancer purposefully shed her chemise on stage in 1927, perhaps under the influence of bootleg hooch. Whatever its true origin, striptease became the sacred centerpiece of topless performance.

Times Square in 1931, with ”The Great Ziegfeld” and to the right, the entrance to Minsky’s Burlesque Theatre. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Times Square in 1931, with ”The Great Ziegfeld” and to the right, the entrance to Minsky’s Burlesque Theatre. (Photo: Library of Congress)

1931: Burlesque on Broadway

The Minsky brothers—Abe, Billy, Herbert and Morton—were the biggest names in burlesque by the 1930s, but their empire had been built on the Lower East Side. Now, with the Depression dragging on and audiences craving escapist spectacles, the Minskys moved uptown.

In 1931 they leased the Republic, one of the oldest and grandest theaters on 42nd Street, and introduced stripteasers (Gypsy Rose Lee was one of their acts) to the Great White Way. Across the street, Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies also featured semi-nude showgirls, but their glittering costumes and enormous feathered headdresses evoked opulence and upper-class respectability.

With the arrival of the Minsky brothers, populist entertainment found fans in the heart of Times Square.

New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in 1940. (Photo: Library of Congress)

New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in 1940. (Photo: Library of Congress)

1937: Party’s Over

New York City’s mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, was driven to reform Times Square’s unwholesome atmosphere (this continues to be a popular mayoral pastime). At the time, the commissioner of licenses, Paul Moss, required all burlesque houses to have exhibition permits that were to be renewed every year on May 1.

At a public hearing in April, religious groups implored Moss to put a stop to the “tide of filth.” One by one, Moss turned down each burlesque theater’s license renewal until topless titillation was effectively outlawed. Perhaps not coincidentally, the following year La Guardia launched a campaign to rid the area of its remaining riffraff before the 1939 World’s Fair.

Times Square in 1941. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Times Square in 1941. (Photo: Library of Congress)

1967: Peep-o-Rama

A Brooklyn-born entrepreneur named Martin Hodas brought peepshows to Times Square. Building on his experience in the vending-machine industry, he convinced the owner of an adult bookstore to install a couple of nickelodeons—which he had found rusting in a barn in New Jersey—that played 16-mm filmstrips of topless women for a quarter.

They were such a hit that Hodas ordered new kiosks and had them installed in at least three other locations, incorporated his business, set up his own studio to make the 16-mm nudie reels, and watched the profits roll in. His employees collected the cash in trunks: in one afternoon, Hodas deposited $15,000 in quarters into one of his bank accounts.

Hodas was later indicted for bribery, tax evasion and allegedly firebombing two rival massage parlors (but was later cleared of the bombing charge).

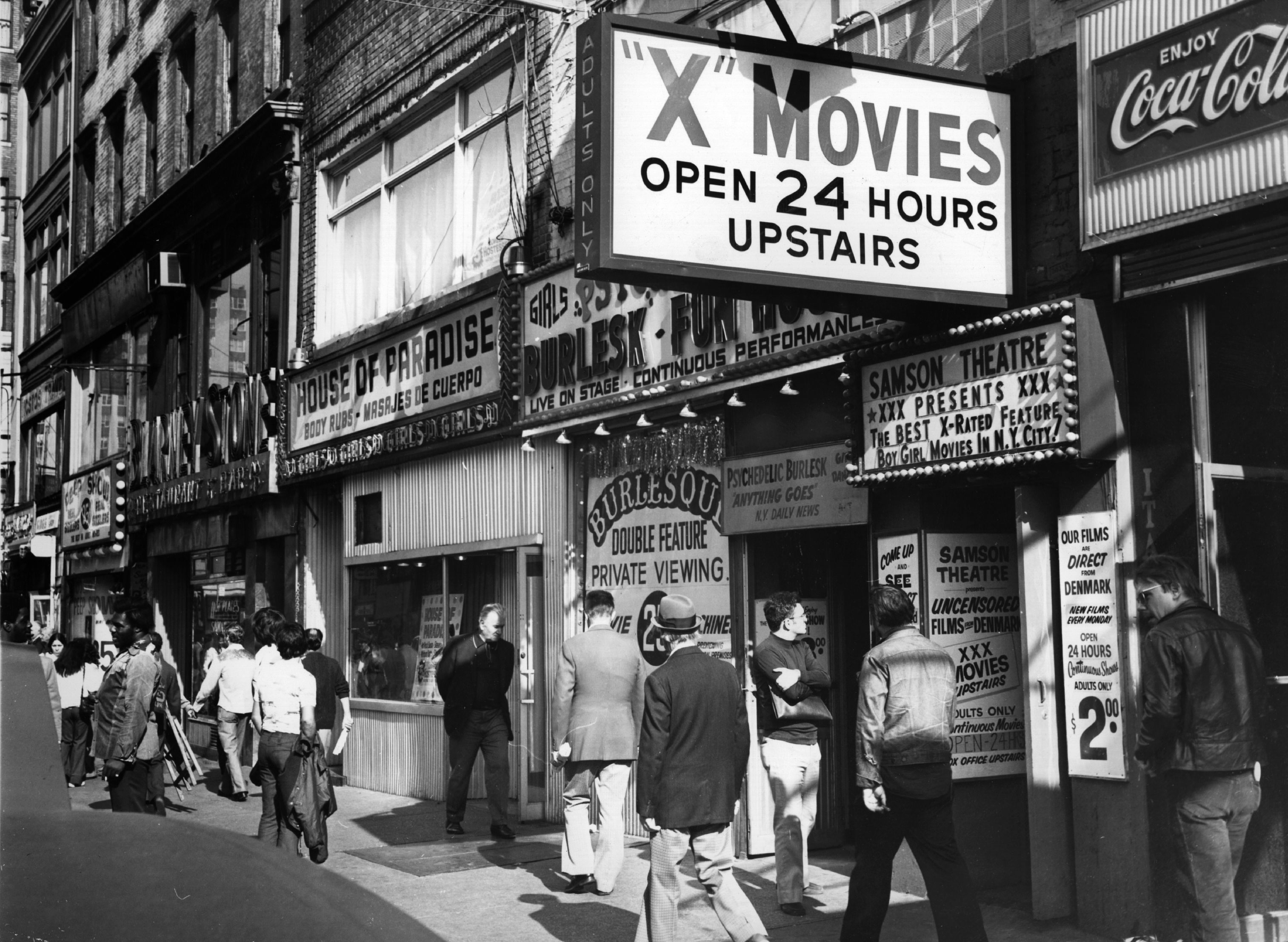

Times Square in 1975. (Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Times Square in 1975. (Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

1975: It’s Show Time

The 1970s brought the golden age of topless entertainment to Times Square. Dozens of semi-legal and downright illegal, Mob-affiliated businesses crowded Eighth Avenue: Hungry Hilda’s Topless Bar, Pleasure Palace, the French Quarter and Show & Tell, plus several movies theaters showing the latest porn flicks, occupied the five blocks between 42nd and 47th Streets.

But Show World Center—a supermarket of strippers, dirty magazines, sex toys and more—stood out when it opened near the corner of 42nd Street and Eighth. With well-lit aisles, orderly shelves of products and a rotating cast of live nude girls, Show World heralded a new, shiny, commercialized era in topless Times Square. In the words of a city official on the vice squad, it was the “McDonald’s of sex.”

1982: Ban Overturned

Back in 1977, bar owners in Buffalo, N.Y. had challenged an existing statewide ban on topless dancing where alcohol was sold. New York’s highest state court ruled in their favor, deciding that banning toplessness in bars was a violation of the freedom of expression, and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with the ruling.

That was good news for the city’s 40 to 50 topless bars, 13 of which were located in Times Square and the surrounding blocks. But despite the legal victory, topless entertainment was suffering an economic slide: a 1982 report from the mayor’s office indicated that the total number of sex-related businesses in Times Square had fallen from 147 in 1976 to 74 by the end of 1982.

Times Square in 2015. (Photo: Guilherme Nicholas/flickr)

Times Square in 2015. (Photo: Guilherme Nicholas/flickr)

1994: The Enforcer

Newly elected mayor Rudolph Giuliani cracked down on Times Square’s sex shops, calling for new zoning legislation that would prevent topless clubs, peep shows and similar businesses from clustering together. Many in midtown Manhattan vociferously opposed the sanitizing Disneyfication of Times Square, a process that included bringing The Lion King musical to 42nd Street.

Despite the protests on free-speech grounds, the legislation passed, and most of Times Square’s topless joints either shut down or moved to designated areas in Queens and Brooklyn. Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum, a 25-screen AMC movie theater, Westin and Hilton hotels, and other major companies set up shop in their place.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook