The Australian School Where Students Live Hundreds of Miles From Their Teachers

A School of the Air student in regional Queensland takes class via two-way radio, circa 1960. (Photo: Queensland State Archives/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

When you’re a kid living in Woop Woop, you can’t just take a bus to school.

Woop Woop is Australian slang for the middle of nowhere. But plenty of school-aged children are living there, in the outback, whether on family cattle ranches or in remote indigenous communities. To get an education, these kids attend the Alice Springs School of the Air. Encompassing 521,000 square miles, roughly double the size of Texas, Alice Springs is the largest classroom in the world.

The school, which began operating via two-way radio in 1951, provides distance learning for around 125 children. Each of these students is located hours from the nearest conventional school. From their homes or a community building, pupils log in via satellite link each weekday to participate in group lessons, which are delivered by teachers at a studio in the outback town of Alice Springs. The kids send in completed schoolwork via email or snail mail to be graded and returned.

The Alice Springs School of the Air is one of many rural education schools now catering to hundreds of remote students in dusty locations across Australia. On a typical school day, students work on assignments from around 8:30 a.m. to 3 p.m., under the supervision of a parent, guardian, or a live-in “govie”—that’s Australian for “governess.” There is generally an hour-long virtual lesson each day, supplemented by written work.

The outback landscape, approaching Alice Springs. (Photo: Andy Mitchell/Flickr)

Art and physical education can also taught over long distances. At the Broken Hill School of the Air (motto: “Parted But United”), gym class consists of children doing pre-assigned physical activities around the cattle farm or “playing set games with their siblings.” The day is broken up by a lunch break and two “smokos.” Smoko was originally slang for “smoke break,” but has now come to mean a snack break.

To account for students’ isolation, teachers at the School of the Air have to get pretty creative with their lesson delivery methods. This is especially important when a video link fails or has not yet been incorporated into the teaching technology–Australia’s broadband infrastructure in remote areas leaves much to be desired, and data transmission speeds are often frustratingly low.

Darryl Cooper, a teacher at Mount Isa School of the Air in Queensland, described his lesson-delivering approach to the Guardian:

Most subjects we can teach. We do the basics, of course, the mathematics, the language, the reading (though mime falls flat). We do manage with things like science activities and experiments, but you have to make sure that whatever you’re using in your lesson is something the children can easily get access to, because they can’t slip out to the corner-store and buy stuff for the lesson. You must use common, everyday things they can get hold of.

Cooper also noted that his students have played musical instruments with one another via School of the Air—a tricky task, given the multitasking involved. “They hold their phones between their knees, that sort of thing,” Cooper said, “and they do very well at it.”

(Photo: LecomteB/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Teachers visit each student at their home once per year to check on their progress and consult with parents. Due to the harsh and lonely nature of the outback climate, teachers generally travel in pairs and check in regularly with their hub school to report back on their whereabouts. If the family reports that the roads are passable, teachers throw groceries and sleeping bags into the four-wheel-drive and head out to see their students. The car invariably arrives back at school encrusted with mud, dust, and the remnants of unlucky bugs.

Though the students’ widely disparate locations means they don’t get to spend much time in the same room, the School of the Air does its best to make kids feel like they are part of a close-knit community. At the Alice Springs school, all students attend a virtual assembly every second Friday, where achievements and birthdays are announced. Around four times a year, students gather in person for up to a week of face-to-face lessons, overnight excursions, and sporting activities. When students travel to in-person classes and excursions, they are required to wear the school uniform, as is the policy in public schools throughout Australia.

The uniform requirement was instituted in the mid ’50s after a chance encounter between two students who both attended School of the Air. “Two families, living over 200 miles apart and never having met, visited the Adelaide Zoo at the same time in December 1956. They met when one student recognized the voice of another student,”explains Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum. This incident, according to the museum, “was the impetus for adopting a school uniform so that students of the school could be easily recognized.”

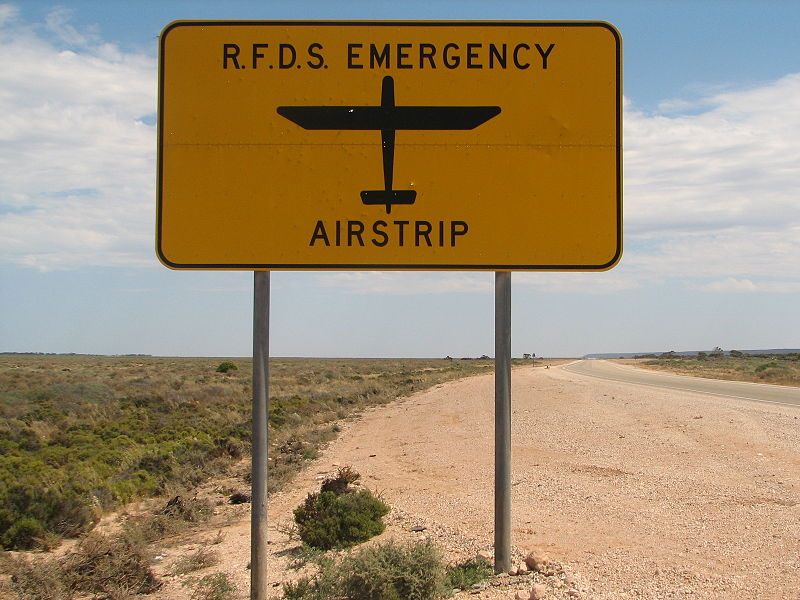

A Flying Doctors air strip in the outback. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The School of the Air’s technologically enhanced approach to rural education is very different from what outback kids experienced in the 1940s. In those days, children in isolated locations would have to do their schooling by mail or attend a boarding school in the nearest big town. That meant a school experience that was lonely, dispiritingly slow, or both.

The first School of the Air came about through the efforts of a woman named Adelaide Miethke. Miethke was then vice-president of the South Australian wing of the Royal Flying Doctor Service, an organization that used–and still uses–planes to deliver medical care to isolated Australians. Taking advantage of the Flying Doctors’ radio network, Miethke began broadcasting lessons to outback children.

Initially, the thrice-weekly lessons were one-way broadcasts, but soon students were able to talk back, and participate in question-and-answer sessions at the end of each half-hour class. In addition to receiving radio instruction, students completed written work and projects, sending them to Alice Springs to be graded and returned. (With the postal service not always reliable, the Flying Doctors would occasionally use their “air ambulances” to deliver schoolwork to teachers.)

Over the decades, technological improvements have made it easier for students to hear lessons clearly, submit their work faster, and even see their classmates and teacher via video. Since 2006, the Alice Springs School of the Air has relied exclusively on satellite technology for lesson delivery. The kids may be isolated, but they get to talk to their schoolmates every day and see them in person on a few exciting weeks throughout the year, when everyone brings a snack to share for smoko.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook