The Chainsaw Artist Who Saved a Pair of Historic Texas Trees

Live oaks are part of League City’s DNA. When two of them got sick, the City brought in a local artist with a beautiful solution.

It’s not unusual for neighborhoods or towns to have rules about what is and isn’t allowed in someone’s front yard. Maybe a specific type of mailbox or door color is required, or there are rules on the type of grass that must be planted and when it can be watered. In the town of League City, Texas, population 110,598, one of their local ordinances is a bit unusual: Every home must have two oak trees in the front lawn. If a resident wants an exception, it better be for a very good reason. And even then, good luck.

League City takes its trees seriously—especially its oak trees. Ten years ago, the city and its residents decided to relocate a century-old oak tree at risk of falling due to a road-widening project; it now lives healthily just a quarter mile from its original home. And then there are the live oaks: League City’s live oak trees, which are featured in the city’s official seal, are, without exaggeration, part of its DNA. There’s one group of oak trees that are especially prized: the “Butler Oaks.”

Earlier this year, the city discovered that two of those majestic trees were severely diseased and beyond saving. Removing them wasn’t an easy decision. “They are a legacy—the towering oaks and sprawling branches are a tremendous part of downtown’s charm,” says Stephanie Polk, manager at League City’s Convention and Visitor Bureau. “We love our trees, and our city is committed to keeping them healthy, so they are around for a long time. When we learned these two had to be removed, we quickly needed to find a solution to repurpose the trees. What was found adds a new chapter to their story.” Enter Jimmy Phillips.

Back in 2008, Hurricane Ike hammered nearby Galveston, Texas, leaving a trail of damaged trees in its wake. Phillips, who lived in the area, had developed a small following for his work carving sculptures out of downed trees using a chainsaw. He worked as a salesman during the day but spent his nights and weekends “carving up firewood,” as he calls it. The native Texan was regularly showing his work at a gallery in Galveston, but the spot was destroyed in the hurricane. One afternoon in 2009, Phillips was visiting potential new galleries when a woman overheard him talking to an owner about his sculptures. “Galveston was still cleaning up from the storm,” explains Phillips. “This woman had it in her mind that she wanted to save the trees that were being cut down all over the place.”

Because of that conversation, Phillips was commissioned to make a few sculptures from Ike casualties that would be displayed at city hall. It turned into a “pretty big deal,” as he says. The pieces were featured on Texas Country Reporter, a popular local news show that’s syndicated all over the state. “After that, I was getting opportunities to carve all over Texas,” recalls Phillips. “I was doing that on the weekends, and during the week, I spent my days pretending to work, then rushing off to carve. I was having a blast!”

Phillips isn’t a “trained” artist in any sense. The 64-year-old credits his high school art teacher and his mother for fueling his creativity but had never considered it a way to make a living—with a wife and three kids, a “real” job was much more sensible. It wasn’t until about 15 years ago, after 30 years of making no art, that his creative fire was reignited. “I had a tree in my front yard that needed cutting down. I was too cheap to hire a proper tree service, so I did it myself,” explained Phillips. “After it was down, I was looking at this huge mass of wood. It seemed like an interesting material, so I started doodling with the chainsaw.” That weekend, he carved out a pelican (which he still has, by the way). “Friends and family started saying, ‘Hey Jimmy, can you do that thing again?’ and I started making shit all the time.” By 2013, he was getting more commissions than he could handle doing it as a side gig. “I quit my proper job, quit getting haircuts, and started doing this thing full time. I’m not getting rich, but I have fun every day—it’s a hoot!”

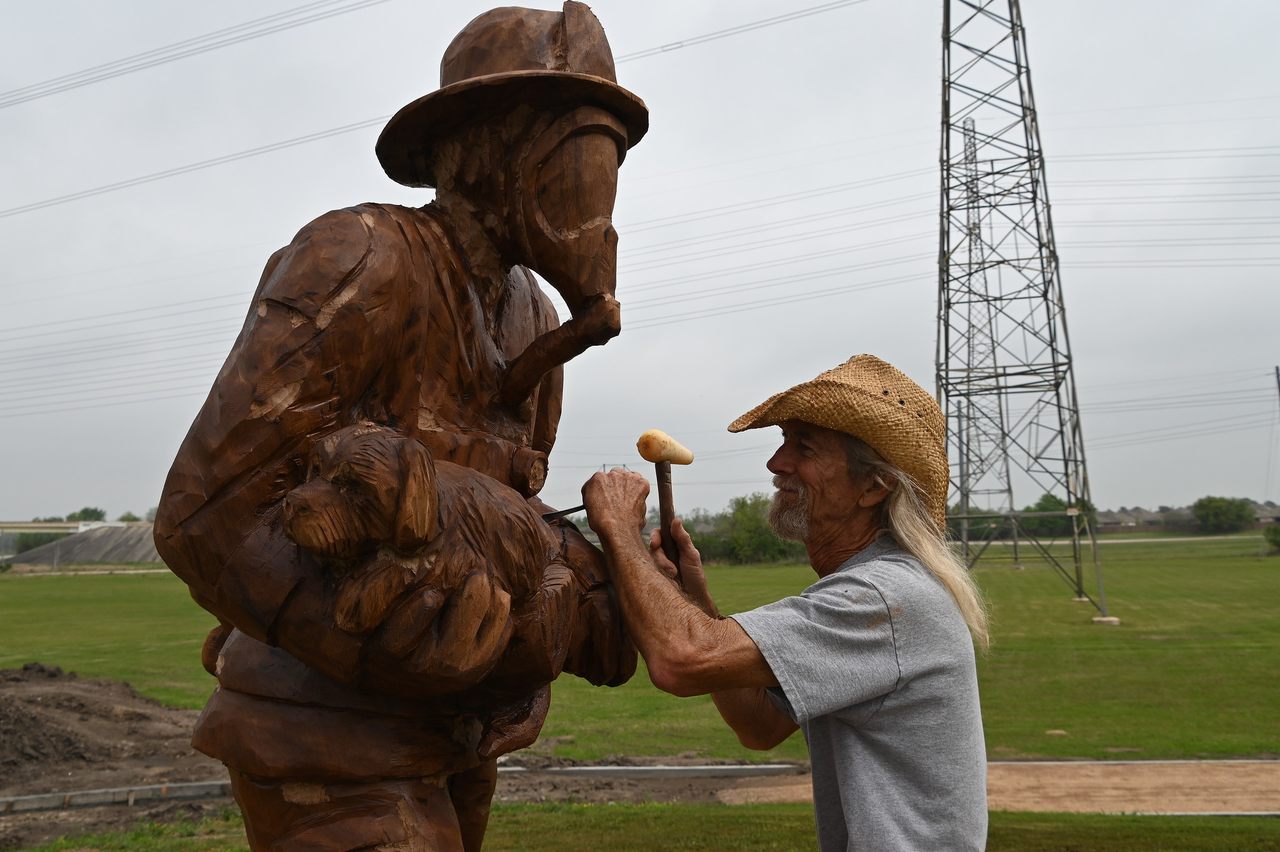

Now, Phillips is doing a series of four sculptures for League City from their beloved oaks as part of a new public art initiative in the city. The first is of a firefighter rescuing a puppy and was recently unveiled at Hometown Heroes Park, a big public recreational space on the edge of town. The second is at the local library and features a young girl reading a book to a dog. (“Everyone brought their dog along with them for the recent unveiling, it was wonderful!” says Polk.) The third piece is a railroad engineer holding a signal light, an homage to the town’s history as a stop on the rail line west. The subject of the fourth will be decided this summer by a public vote.

“It’s too much fun,” says the now long-haired Phillips. “Curious children come up to me all day. I do my shtick and make them look through my little books,” says Phillips, referring to a couple of not-so-little picture albums he keeps of his studio work and tree sculptures. “I am the luckiest guy I know.”

This post is sponsored by Visit League City. Click here to explore more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook