The Congressman Who Brought Belly Dancing to America

It all began with “abdominal gyrations” at the World’s Fair.

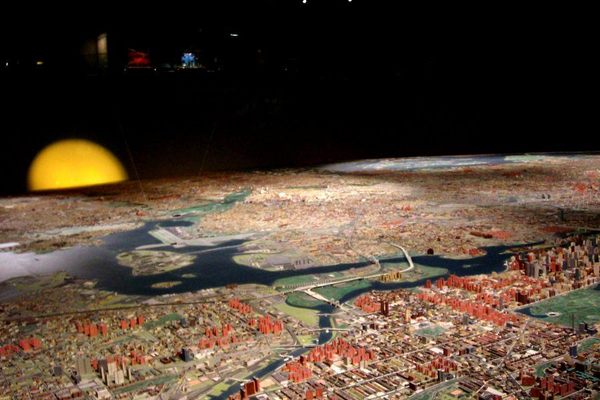

A view of Chicago’s World Fair, 1893. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-128873)

The bombastic copy on the dust jacket of Sol Bloom’s 1948 autobiography proclaims him “one of the world’s most distinguished and influential citizens” and “a great American.” Bloom was indeed an influential citizen, as well as a 14-term United States congressman, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and delegate to the conference that established the United Nations.

But Bloom’s most lasting contribution to American society had nothing to do with politics. He holds the curious distinction of being the person who introduced belly dance to American audiences.

Born in 1870 in Pekin, Illinois, Solomon Bloom was the son of Orthodox Jewish Polish parents. Bloom claimed to have only attended school for one day in his entire life, crediting his mother with most of his education. Like many of Bloom’s statements, that claim is probably a mixture of truth and showmanship.

When the family moved to San Francisco early in his life he quickly found small jobs at the local theatres and began working his way up in the entertainment business. In 1889 he traveled to the Exposition Universelle in Paris, looking for both culture and new opportunities. He quickly became enamored with the Algerian Village, one of a group of exhibitions focused on the French colonies. In The Autobiography of Sol Bloom he wrote: “I doubt very much whether anything resembling it was ever seen in Algeria, but I was not at the time concerned with trifles.”

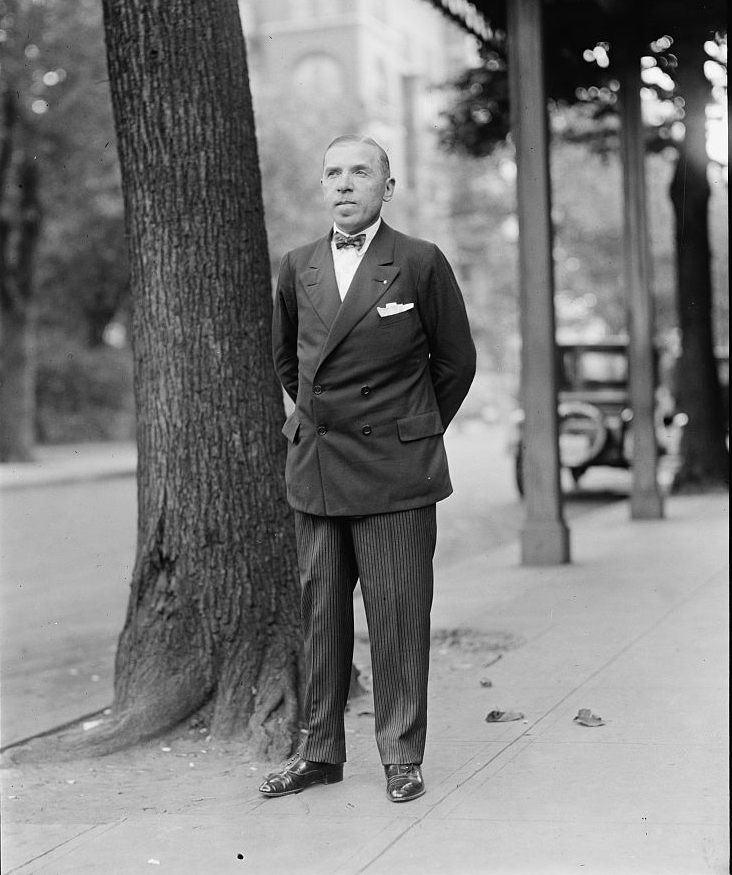

Sol Bloom circa 1923. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-F8- 25645)

What Bloom was concerned with was money. “I knew that nothing like these dancers, acrobats, glass-eaters, and scorpion swallowers had ever been seen in the Western Hemisphere,” he wrote, “and I was sure that I could make a fortune with them in the United States.” At the close of the exposition he secured a two-year exclusive contract to book the Algerian Village and its performers for shows in North and South America.

Bloom then quickly returned to the United States to begin looking for a venue for his new acquisition. Finding a lack of enthusiasm for his Algerians in New York, he boarded a train for Chicago. He had heard that Chicago was likely on the verge of securing the contract to host the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition—also known as the World’s Fair—and he was sure his Algerian Village would be a marvelous addition.

His enthusiasm landed him in town almost three years early, but ultimately the 21-year-old Bloom would walk away from his Chicago meetings as the well-paid manager of the fair’s entire Midway Plaisance array of amusements.

The fair’s planners had originally envisioned the Midway Plaisance as a separate area that would house cultural and educational exhibits. In an effort to increase revenue this plan was soon amended to include other entertainments, the most memorable being the world’s first Ferris Wheel. Bloom’s Algerian and Tunisian Village, usually just referred to as the Algerian Village, would find its place on the mile-long Midway among other such villages including those representing Germany, Japan, Turkey, and Egypt. There was also an ice railway, an ostrich farm, and a captive hot air balloon ride.

The World’s Fair ostrich farm. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

Among the amusements in the Algerian Village was a 1000-seat theatre that was open as early as the summer of 1892. Due to an error in communication, the Algerian performers had arrived from Paris a year early and Bloom was anxious to begin making a return on his investment. The theatre presented one of Bloom’s favorite acts, a group of dancers he referred to as a ballet troupe performing the danse du ventre.

Also referred to as “oriental dance,” danse du ventre was the French term for a variety of dances performed in North Africa and the Middle East. At the time, Westerners collectively referred to these areas and parts of Asia as “the Orient.” The romanticized and exploitative presentation of people from these areas in writing, art, and advertising was incredibly popular at the time. As researcher Donna Carlton notes in her book Looking for Little Egypt, it was against this backdrop of “exoticism” and “ignorance” that danse du ventre debuted in Chicago.

A stereoscopic view of “Cairo Streets” at the World’s Fair. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

Carlton writes that she believes “there were sincere attempts to present this dance in at least three Midway Plaisance exhibits.” Among the performers were Ghawazi dancers from Egypt, members of the Ouled Naïl ethnic group from Algeria, and Turkish-style çengi dancers, known for whirling with handkerchiefs and castanets at Ottoman Empire court dances. There was also a fourth concession on the Midway that “featured Parisian dance hall entertainers who presented a debased imitation version.”

Bloom lauded the dances as “sensuous and exciting, a masterpiece of rhythm and beauty.” Others, like a letter writer to the Chicago Tribune, described the movements as “abdominal gyrations,” and a reporter for the Princeton Union wrote about the “hellish contortions” and “abomination known as belly dance.” It was this name for the dances that Bloom thinks really drummed up the initial interest. “When the public learned that the literal translation [of danse du ventre] was ‘belly dance’ they delightedly concluded that it must be salacious and immoral,” he said 60 years after the fair. “The crowds poured in. I had a gold mine.”

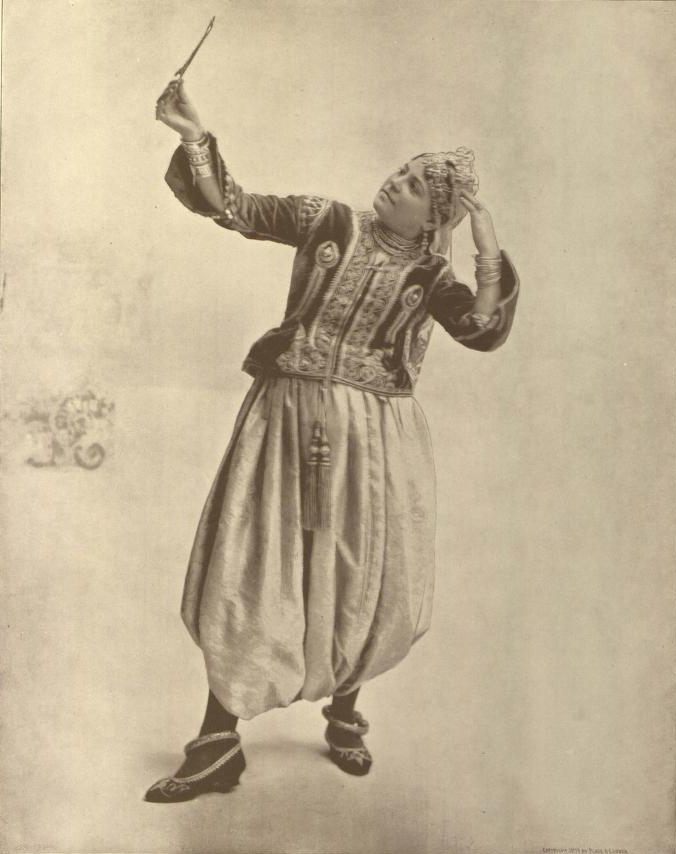

A portrait of Salina, one of the dancers in the Algerian Village. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

The fervor over the dance reached its peak when the country’s preeminent vice hunter, Anthony Comstock, head of New York’s Society for the Suppression of Vice, toured the fair and wrote a scathing report about the dancers. When the members of the fair’s Board of Lady Managers read the report’s lurid details they decided something must be done to put an end to the vulgarity. Finally a directive to shut down the Persian Palace theatre was given, and promptly challenged by the theatre’s management. While the directive was a warning to all of the theatres presenting danse du ventre, it should be noted that the Persian Palace was the venue featuring the Parisian dancers and their notorious imitation of oriental dance.

The ‘Turkish Village” at Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. (Photo: Public Domain)

In addition to introducing Americans to belly dance, Bloom also claims credit for creating another piece of faux Arabian fantasy. Prior to the opening of the fair Bloom was invited to present a preview of danse du ventre to the Press Club of Chicago. Delighted at the chance for free publicity, he brought around 12 of the Algerian dancers but apparently failed to bring the musicians. When the pianist at the event asked what music the performers should dance to, Bloom says he made up a tune on the spot, plucking out a quick set of notes on the piano. This melody, possibly based on a traditional Algerian folk song, is often called the “snake charmer song” because of its ubiquity in cartoon snake charming scenes. Bloom did not copyright the song, and various versions were published during this era, including the popular “The Streets of Cairo or The Poor Little Country Maid.” Perhaps the best-known lyrics for this music begin “There’s a place in France where the naked ladies dance…”

After the close of the World’s Fair, Bloom continued his career in entertainment, working in sheet music publishing and sales for many years. It wasn’t until 1922, at the age of 52, that he entered politics, winning the House seat as a Democrat for New York’s 19th District. As for belly dance, other promoters quickly ran with its success and it began to appear at amusements parks and carnivals across the country.

“Little Egypt”, a dancer at the Midway. (Photo: Public Domain)

Legends also began to circulate about a scandalous “Little Egypt” who had shocked audiences on the Midway, with many of the new amusements claiming to have Little Egypt as their star performer. Three women are often highlighted as the original Little Egypt: Fatima Djemille, Farida (Fahreda) Mahzar Spyropoulos, and Ashea Wabe (the most likely candidate to first use the moniker). The first two women probably did perform at the fair, but there is no record of either of them being called Little Egypt at that time.

The idea of Little Egypt proved too scandalous even for Bloom, who denied he had anything to do with any performer who went by that name. But in his autobiography, he went on to acquiesce: “I know what happens to people who protest too much: they reinforce the legend they are trying to destroy. So I am resigned to probable immortality as the man who gave Little Egypt to the world. If I am very lucky, perhaps one or two of my real activities will be recalled along with this fiction.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook