The Man-Made Gut Stones Once Used to Thwart Assassination Attempts

Gilded Goa Stones couldn’t cure poison, but they sure were beautiful.

A man-made bezoar known as a Goa Stone. (Photo: Fæ/CC BY 4.0)

Poisoning used to be a much more effective method of doing away with your enemies, thanks largely in part to the ineffectiveness of historical antidotes and medicine. One fabled poison cure was the bezoar, a hardened spherical deposit of indigestible material that forms in the gastrointestinal tract of hoofed animals.

For hundreds of years, bezoars were believed to be able to render any and all poison inert. And when you couldn’t get your hands on a naturally occurring bezoar, you could, for the right price, opt for an artificially created bezoar known as a Goa Stone.

Bezoars, which appear as stone-like lumps, can form from hair, seeds, fruit pits, rocks, calcium, or pretty much anything that has trouble passing naturally through an organic system. They are most often formed in the bodies of hoofed animals like goats or deer, although bezoars taken from Asian porcupines were also popular.

As to their healing properties, it was believed that you could either ingest some crushed up bezoar, or more commonly, drop a bezoar into a drink that was suspected of being poisoned. If you were too poor to afford a bezoar of your own, you could work around it—alchemists were known to rent them out for general healing.

A collection of natural bezoars. (Photo: Schtone/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Possibly the most famous use of a bezoar was in an experiment by the 16th-century French surgeon Ambroise Paré, who set out to prove that they were not actually the cure to all poison. A cook sentenced to be hanged agreed to be poisoned instead, just so long as he could be administered a bezoar immediately after, to be set free if he lived. The cook died just hours later, and Paré’s experiment had proved that the power of the bezoar was not quite what it seemed.

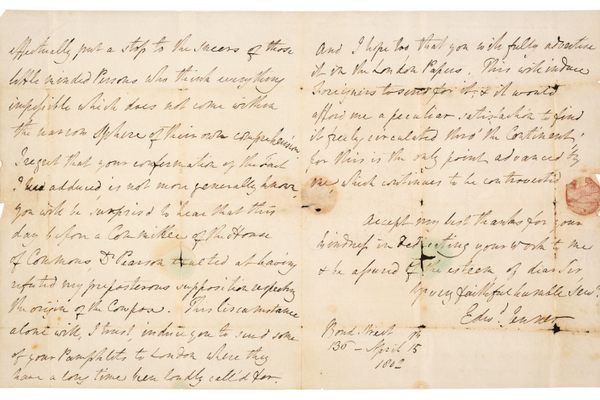

However, even with Paré’s deadly experiment proving that bezoars weren’t magic, their fabled efficacy wasn’t so easily defeated. By the 17th century, a group of Jesuit monks in the small Indian state of Goa had begun manufacturing artificial bezoars to sell to wealthy English patrons and royalty. The polished balls of crud were made of all sorts of strange ingredients including narwhal horn, amber, coral, and crushed-up amethyst, emeralds, and other precious gems, to name a few. Sometimes they would even include bits of a naturally occurring bezoar. The makers of the Goa stones still believed in their usefulness as a cure-all, as did the rich recipients who purchased them for as much as 10 times their weight in gold.

A less ostentatious Goa Stone. (Photo: Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

Tiny slivers of the fist-sized balls would be shaved off and mixed into drinks to thwart assassination attempts or cure sickness, but the stones themselves were also seen as status symbols (as traditional bezoars were often considered). Thus many of the Goa stones, or at least the surviving ones, were encased in ornate gold and silver orbs. The stone’s casings were a sharp contrast to the muddy-colored balls of pseudo-magical detritus inside, looking like intricately carved cages. Arabesque designs with intertwining lines were mingled with animal symbols, including, in some cases, mythical creatures like unicorns.

A rise in the sale of artificial bezoars, possibly including Goa stones, that contained unhealthy minerals like mercury, actually ended up making people more sick, leading to the use of the stones waning around the 1800s. But the use of bezoars as healing items can still be found in Chinese herbology.

Today a few Goa stones are on display in museums including one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and another in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria. They are gorgeous to look at, but relying on them to stop any poisonous assassination attempts is not advised.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook