The Maps That Helped The Citizens Of A ‘Locked Country’ See The World

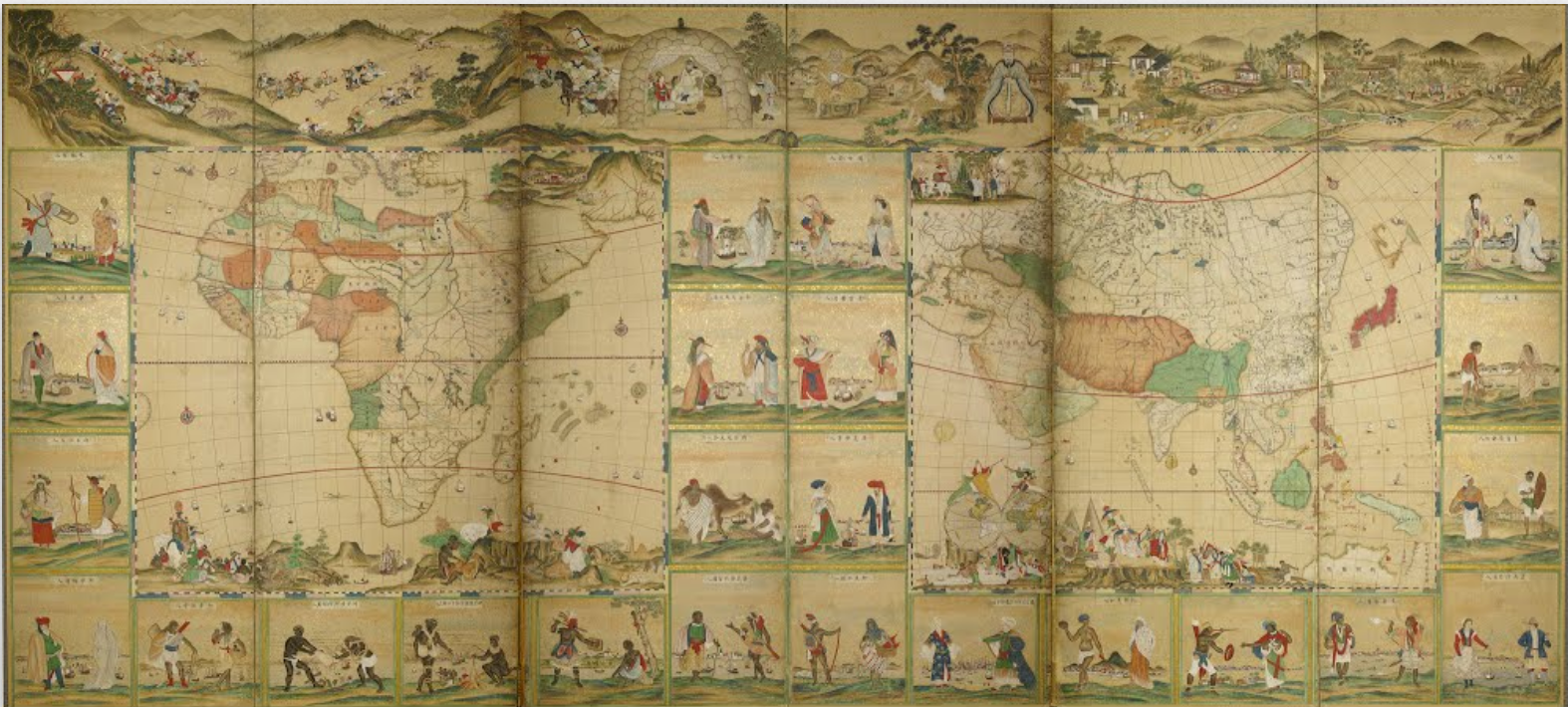

Half of “Screens of the Four Continents and People in 48 Countries in the World,” by an unknown Edo-era Japanese painter. (All images: Kobe City Museum/Google Cultural Institute)

Generally, the scale of a map determines what it’s used for. A global map gives an extensive look at the world, and can spur an overwhelming appreciation for the sheer scale and variety of the place. A local map lays out the minutiae of day-to-day experience—small streets, landmarks, and other visual markers we then imbue with our own memories and emotions.

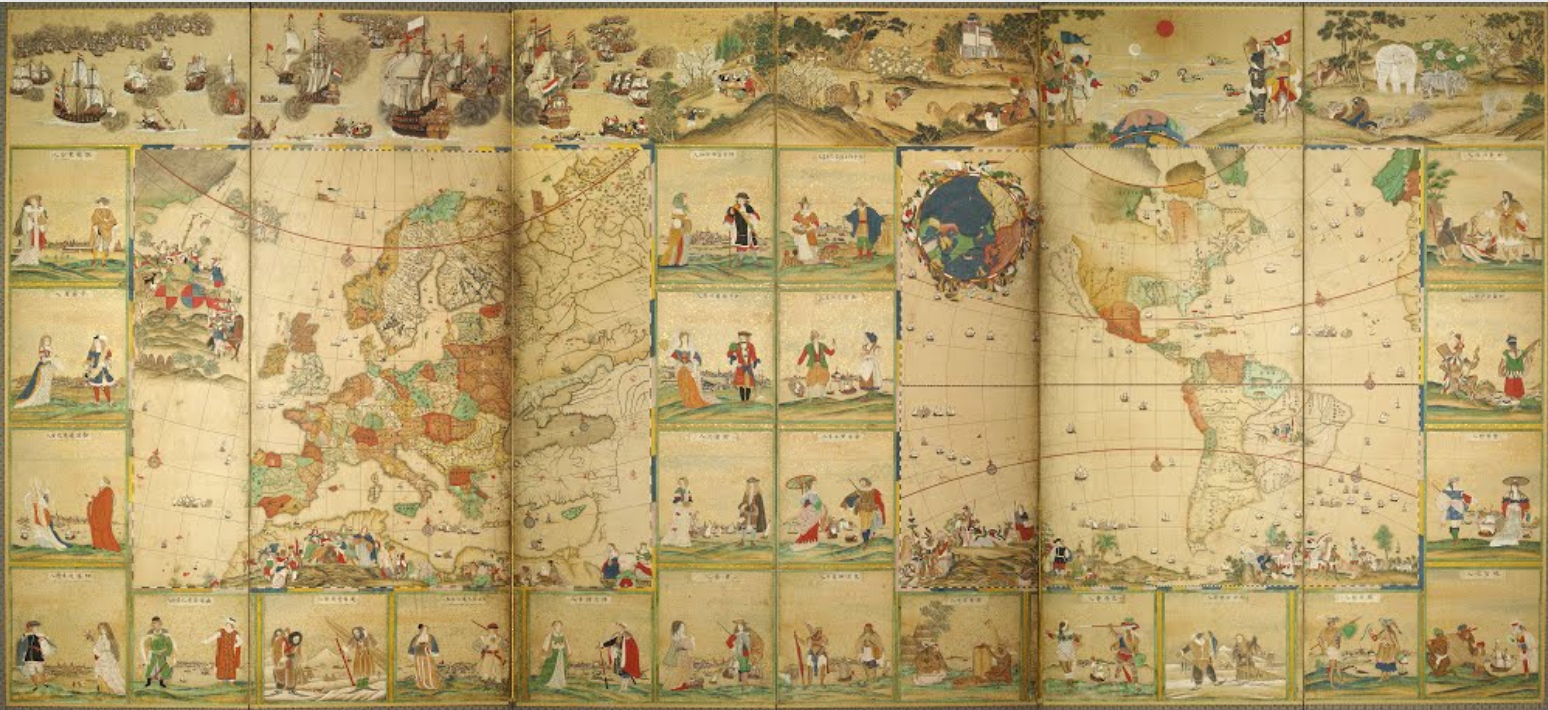

But it’s a rare map that manages both overviews and close-ups; that inspires both awe and intimacy. The two surviving ”Screens of the Four Continents and People in 48 Countries in the World,” by an unknown Japanese painter, beautifully lay out the geographical arrangement of the planet, with carefully delineated countries, seas, rivers, and mountain ranges. But, like the 18th century equivalent of a National Geographic box set, they also provide detailed, surprisingly affecting snapshots of that planet’s residents.

Two couples, a continent apart, live out their daily lives next to each other on the map.

Arranged in boxes around the continents, pairs of model citizens, dressed in culturally appropriate garb, go about their daily lives. Next to Madagascar, an African couple, draped in white linen, tends to a long-horned cow; across the embossed border, a Chinese man gestures at incoming ships, while his wife shades her face behind a fan. The map of Europe and America juxtaposes an Inuit family, backed by a whale-filled sea, with two expensively dressed Europeans overlooking a bustling town. Throughout, there are warriors, traders, musicians, fishermen, large and small families, and even, in the bottom left corner of the Africa/Asia map, a cannibalistic duo.

Americans rub elbows with Europeans.

The maps—which are over five feet tall and just under 12 feet wide—were originally attached to a latticework of wood to form a byobu, or folding screen. Byobu are light and flexible, and can be used to divide architectural spaces into any number of configurations. Extended fully, they add decoration to the middle of a large room; bent to encompass a corner, they form an intimate space. Placed next to each other and folded along the visible creases, these particular maps could have wrapped 18th century viewers in a panoramic view of the known world, complete with plenty of ambassadors.

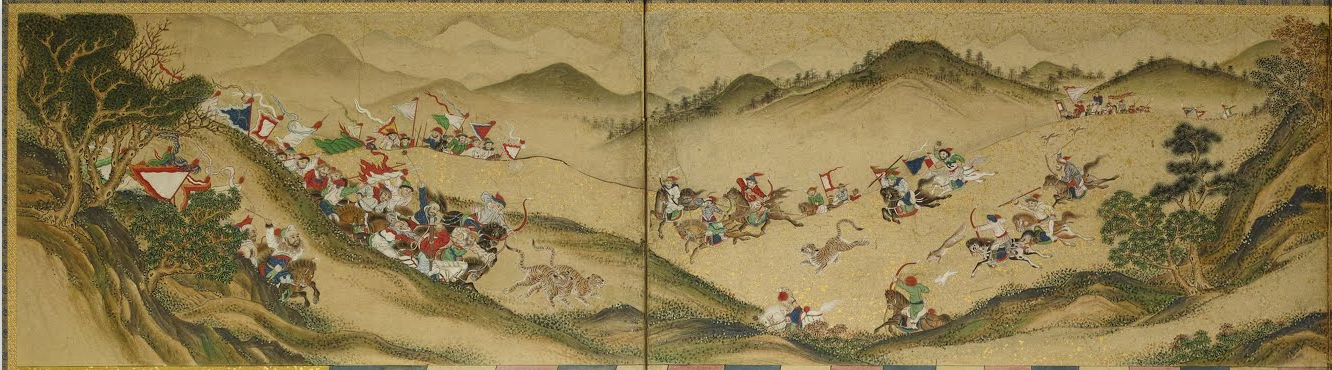

Detail from the upper border of the Africa/Asia map.

The paintings date to sometime between 1718 and 1800, during a middle stage of the Edo period. During this time, Japan was isolated from much of the world due to the reigning shogunate’s Sakoku, or “locked country,” foreign policy program. Sakoku threatened death to anyone who crossed the border in either direction—adding extra pathos to this unknown artist’s renderings of friendly foreigners.

The second half of the set.

The screens were displayed at the Kobe City Museum in Kobe, Japan this past summer. You can explore them in full digitized detail thanks to the Google Cultural Institute—Africa and Asia are here, and Europe and America are here—and imagine what it would have been like to be surrounded by such diversity, with no hope of ever seeing it for yourself.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook