A Walking Tour Retraces Lisbon’s Painful Legacy of Slavery

It also highlights the city’s modern-day African communities.

Naky Gaglo begins his tours of Lisbon in Praça do Comércio, a grand plaza that once served as the commercial business district of Lisbon. Today, most tourists focus on the lemon-colored buildings and the triumphal arch, built to honor Lisbon’s survival and reconstruction after an earthquake in 1755. But Gaglo brings his tour to the plaza for a different reason. Slave ships once moored here along the Tagus River. Gaglo starts in Praça do Comércio because he wants his group to begin to imagine how the architecturally stunning district acted as a brutal epicenter for human trafficking.

“[This is] the other side of Portugal that isn’t well-known—the African side of it,” Gaglo says. “In Europe, slavery is not taught the way it should be. I’m just trying to uncover what the secrets are and educate people about an important part of the history.”

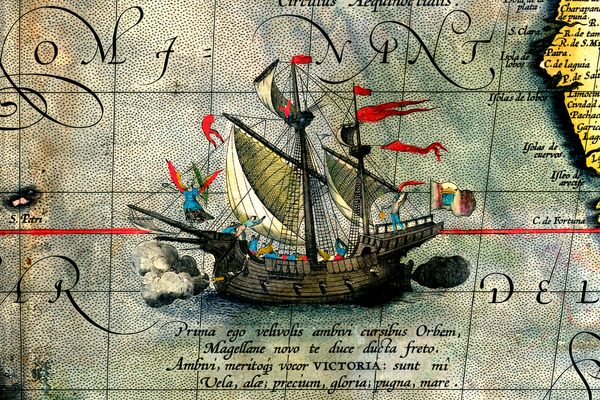

Portugal was responsible for shipping 4.9 million people from Western Africa to Brazil, by far the largest amount of human cargo transported during the Atlantic slave trade. And yet, while traversing the cobblestone streets of Lisbon, or sipping the barrel-aged red wine in Porto, there is little hint of the country’s role in participating in one of the bloodiest man-made atrocities in human history. It’s a missed opportunity to explore one of Europe’s most breathtaking countries by taking an honest look at how culture, history, and racism still shape this gem on the Iberian Peninsula, as well as to highlight the rich cultural diversity of the country today.

That’s why Gaglo decided to do something about it. Originally from Togo, he runs the African Lisbon Tour, a five-hour English-language walking tour through the capital city’s center that unravels the complexities of Portugal’s colonial past with intelligence and finesse, drawing clear, insightful relationships between past and present.

“We don’t have very much about slavery here,” Gaglo says. “There are almost no monuments or museums. Sometimes you have exhibitions, but there’s really nothing that is relevant.”

Considering that Lisbon has a substantial African community, he finds it incomprehensible that there hasn’t been a larger initiative to educate foreigners or even locals about Portugal’s part in the slave trade. While official statistics of African inhabitants aren’t known, because the Portuguese Census doesn’t ask questions about ethnicity, the cultural makeup of the city conveys an atmosphere of richness and diversity.

“We have [people] from Mozambique, Angola, and Cape Verde,” says Gaglo. “It’s a shock to tourists, but it’s a positive shock. The culture is very vibrant here.”

The tour adds a somber dissonance to Lisbon’s aesthetic charm. As Naky guides the group, 15th-century neighborhoods built from intricate mosaic tiles become fraternal meeting grounds for Africans seeking refuge. The neighborhood of Mocambo, for example, now referred to as Madragoa, served as a place of both extreme duress and sacred assembly. In Mocambo, slave owners’ were often negligent of their human chattel who, after dying, were left to rot on the streets, causing significant sanitation and public health concerns. As a result, in 1515 King Manuel I ordered that a massive burial site, known as Poço dos Negros, be built and filled with quicklime—a site now replaced with shops and markets.

Mocambo was also a significant meeting ground for slaves to practice their traditional West African beliefs. It’s where they buried bolsas de mandinga (mandinga bags), sacred talismans worn by men meant to ward off evil spirits, and took part in traditional religious ceremonies in accordance with what many Afro-Brazilians now practice as Candomblé.

Naky also takes the group to Rua do Comércio, which once sheltered a bustling slave market at Terreiro do Pelourinho Velho, where human lives were bartered. The tour then stops in the nearby neighborhood of São Bento. Now home to many bustling shops, São Bento became a prominent Cape Verdean neighborhood in the 1960s. It’s here where Naky and his group take a mid-tour break at an African restaurant that provides a delicious assortment of West African food and drink, such as spicy pork, tuna, or tofu with cachupa, a Cape Verdean dish of corn, beans, and cassava. It’s an ideal moment for both tour guide and tourist to discuss what they’ve learned and reflect on how it might challenge preconceived notions of Portugal’s past.

Afterward, the tour passes the Memorial as Vitimas do Massacre Judaico de 1506 in Rossio Square, a monument that remembers the victims of the anti-Semitic campaign that resulted in the execution of an estimated 2,000 to 4,000 people, who were accused of being Jewish. It was a critical event that is seen as one of the factors leading up to the Portuguese Inquisition, which formally began in 1536. It’s an interesting place to take the tour, because this location was also where slaves gathered for different forms of spiritual assistance and brotherhood during the 15th century, and demonstrates that the viciousness of ethnic and religious persecution affected many communities during Portugal’s colonial era.

The tour ultimately concludes near a statue at the Praça Dom Luis, named after the Portuguese king who reigned during the bloody Scramble for Africa.*

By using this history as an anchor in his tour, Naky contextualizes the integration of modern-day African communities. He shines a light on African businesses, music, art, and especially food.

“Even after the tour, they’re really amazed by the history,” Gaglo says of his participants. “They really like the fact that it’s not a European tour; it’s an African tour. They like having something different. This is my biggest motivation for doing it.”

Because the tour is done entirely by foot, Naky is able to guide tourists through parts of Lisbon that would not normally be discovered, and his extensive research into the subject makes it well worth the physical exercise. His tour, and the conversation it has helped to stimulate, may also be making a difference. Toward the end of 2017, Lisbon residents voted to finally erect a memorial to commemorate the millions of Africans that fell victim to the slave trade, sparking a heated debate about the true nature of Portugal’s role in slavery and the need for public accountability. No doubt, if and when completed, it will provide an invaluable opportunity for education, as well as an excellent addition to Naky’s tour.

*Update: This post has been updated to reflect recent changes in the tour itinerary.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook