Even More Ways to Help Librarians and Archivists From Home

As long as we’re all cooped-up, here are six digital projects that could use your curiosity.

A couple weeks ago, we shared six digitization and transcription projects that curious and cooped-up readers can contribute to from home. As countries continue to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, many libraries and archives remain closed, and will likely stay shuttered for months. In the meantime, try sublimating your intellectual wanderlust with more ways to give researchers a (virtual) helping hand. These projects won’t help you stretch your legs, but they will give your brain a workout.

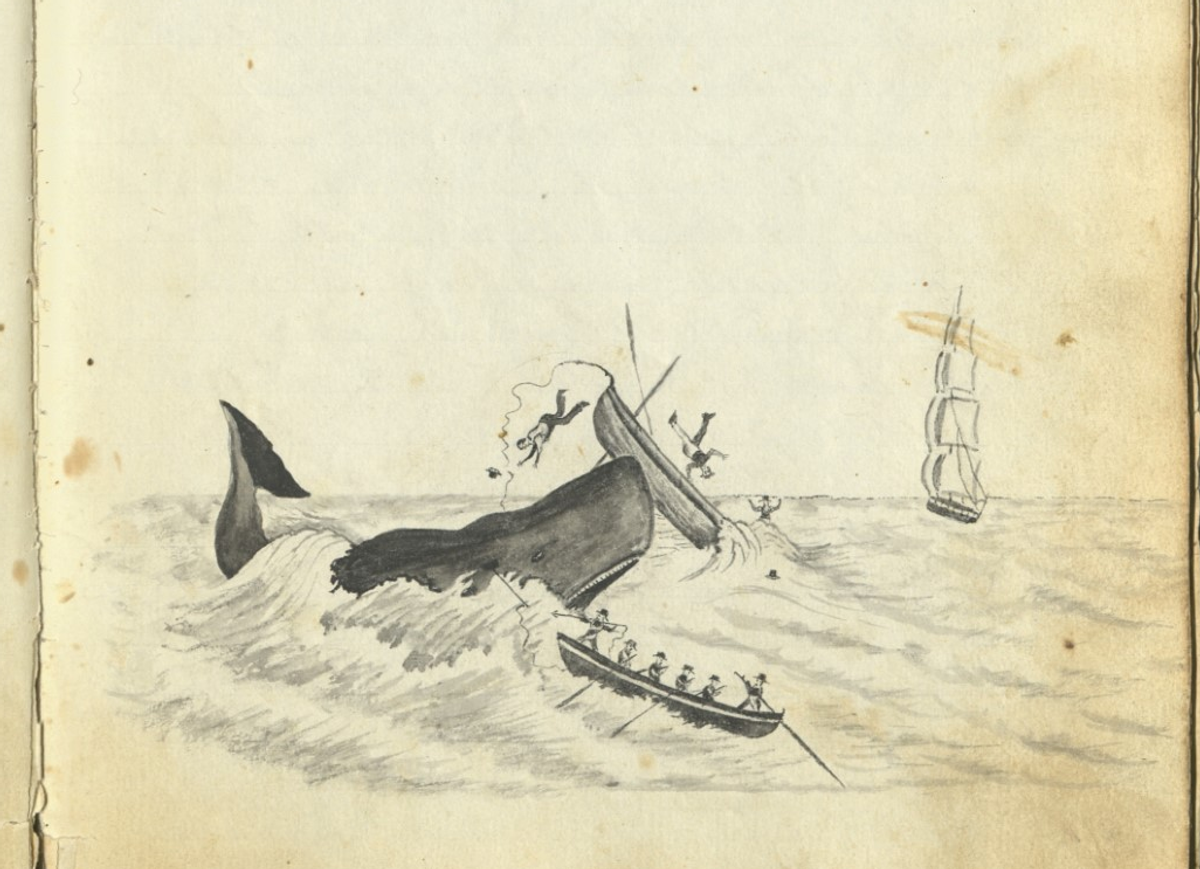

While away the hours with New England whaling logs

Nantucket was once a beating heart of the American whaling industry—and though harpooners are no longer slicing through choppy waters in pursuit of leviathans, they left a prodigious written legacy behind. Unfortunately for contemporary scholars, the log books that kept track of daily life aboard the ships are often scrawled in cursive that is tricky to read. Since October 2019, the Nantucket Historical Association has been working to digitize and transcribe its collection of more than 400 log books, including 11 kept by seafaring women. “Many of the logs are illustrated and feature poetry and personal anecdotes,” writes Sara David, the digitization archivist at the institution’s research library, in an email. “Some of them read like they could be Moby-Dick.”

If you’re ready to help decipher the salty scribbles, log on to the project portal on From the Page, a hub for crowdsourced transcription, and sail through logs such as the richly illustrated one kept by Milo Calkin, who shoved off Nantucket on a whaling ship called Independence bound for the Pacific Ocean. He found himself quite at home. “I very soon became familiar with the duty of managing the ship,” he wrote. “And if I could only have learned to chew tobacco, drink rum, swear and lie I should have made a first rate sailor.”

Escape the Earth with science-fiction fanzines

What better time to zip into a happily unfamiliar realm? The DIY History project at the University of Iowa Library, which invites people to help transcribe digitized objects from the library’s special collections and other holdings, could use your help with its massive trove of science-fiction zines. Some date back to the 1930s; all were collected by the late James L. “Rusty” Hevelin. More than 10,780 pages of the Hevelin Fanzines collection have been transcribed so far, but there are still around 500 left to go. If you need a mental break from this planet and its familiar troubles, pop into this project and spend a little time somewhere else.

Dig into Alabama history with diaries and licenses of note

The Alabama Department of Archives and History brims with documents, and many of them need to be transcribed. These include the 1891 medical licensure exam written by Halle T. Dillon, a black woman who studied at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and would go on to become the first woman licensed as a doctor in Alabama. As you read through her responses, you’ll also get a crash course in obstetrics, anatomy, and more. If all that detail has you feeling a bit faint, try the diary in which Lavinia Bright Walker—an elementary school teacher who moved from Alabama to Detroit as a child, in 1920—jotted down her young-adult musings about dating, fashion, and more, with the larger issues of racial tensions and economic struggle rumbling in the background.

Fix up transcripts from public broadcasts

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting, a collaboration between the Library of Congress and the station WGBH in Boston, is recruiting volunteers to help tidy up transcripts of public radio and television programs seen and heard around the country. The FIX IT+ initiative asks participants to comb through computer-generated transcripts and correct the mistakes, making it easier to search, say, a conversation with James Baldwin, or a visit to a soap company in upstate New York. Several thousand programs, spanning 60 years, are still waiting for someone’s eyes, ears, and fast-typing fingers.

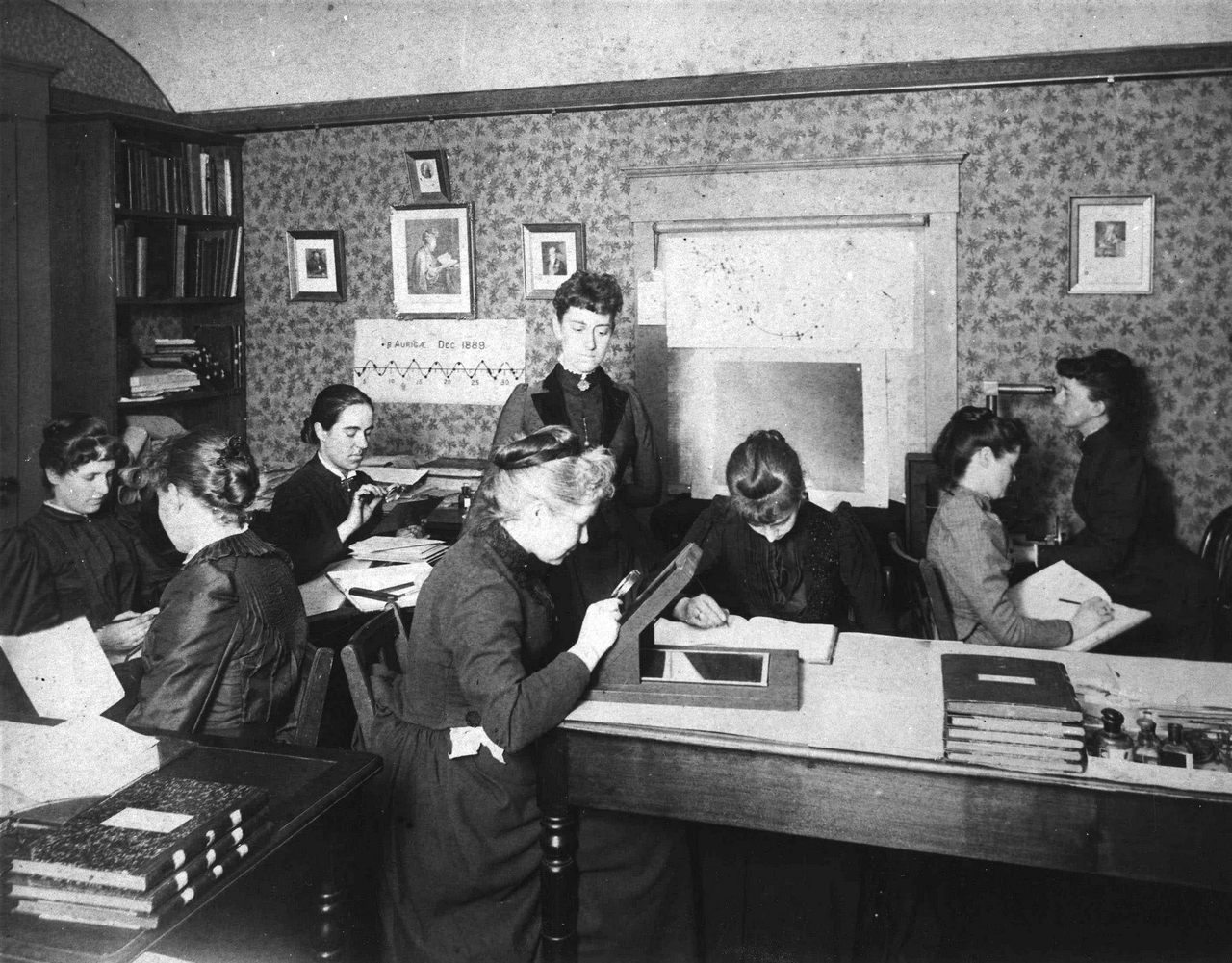

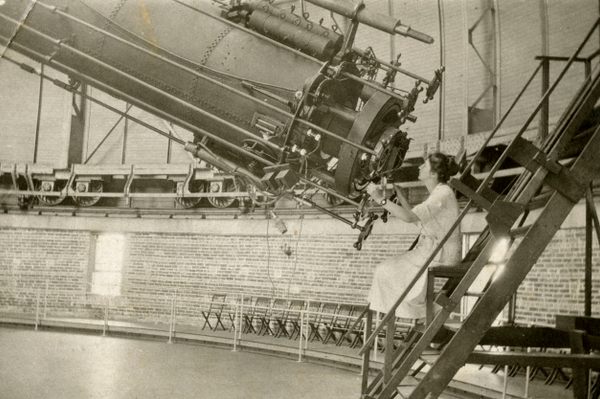

Gaze into celestial notebooks and photographs

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, dozens of women hunkered down at Harvard to study the sky. Known as the Harvard Computers, these workers were tasked with comparing, classifying, and cataloguing objects in the sky, mainly based on photographs. Some, including Annie Jump Cannon, who discovered several new stars and hatched a new idea for a star-classifying system, went on to achieve some measure of individual fame—but many of their contributions were eclipsed by the larger project at the Harvard Observatory and the renown of Edward Charles Pickering, who directed it.

Now, the Wolbach Library at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics is enlisting help with a newer endeavor, called Project PHaEDRA (or Preserving Harvard’s Early Data and Research in Astronomy). One arm of the project involves transcribing several Computers’ notebooks; the Star Notes portion asks people to digitally leaf through those notebooks in search of plate numbers, which will allow researchers to match notebook entries with the glass plate photographs the women were referencing. To participate, sign up here.

Type up essays in the American Prison Writing Archive

Since 2012, the American Prison Writing Archive at Hamilton College has gathered 2,340 essays by incarcerated writers. (The project, which is backed by the National Endowment for the Humanities, solicits submissions through newsletters circulated in prisons.) America imprisons people at a higher rate than any other country, and the project invites the 2.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S. to tell their stories in their own words. Many of these reflections are handwritten, and Doran Larson, a professor of literature and creative writing at the college, welcomes help from people who are able to type them up. If you’d like to transcribe, fill out the application.

Do you know of any other ways to help archivists and librarians from home? You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook