A Blizzard of Tumbleweeds Caused a 10-Hour Traffic Jam in Washington State

Cars slowed to a halt on State Route 240, but the plants just kept bounding along.

Come winter, salt trucks and snowplows try their best to protect drivers from slick roads. But a few days ago, on New Year’s Eve, a stretch of highway near Richland, Washington, was faced with a different sort of winter foe: Not a blizzard or an ice storm, but a terrible confetti of thousands of tumbleweeds. Officials dispatched snowplows to wrangle them.

If you’ve ever seen a Western film, you might associate the coasting, desiccated bundles with ghost towns. In much of contemporary America, though, tumbleweeds are still common sights. They’re the last stage of the life cycle of plants commonly known as Russian thistle (an umbrella term that includes Salsola tragus and several other species), likely introduced to America from Eurasia in the 19th century. Tumbleweeds spread by breaking off and bounding away, flinging seeds wherever the wind carries them.

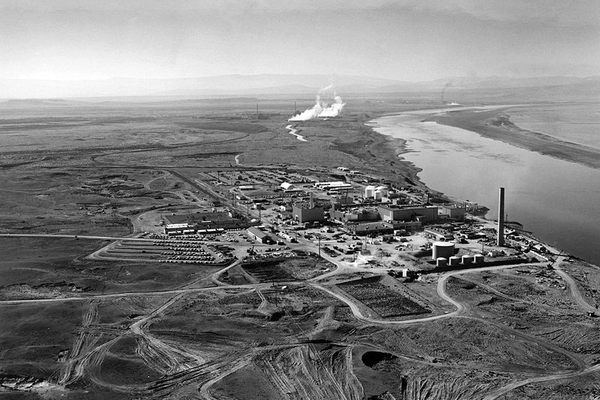

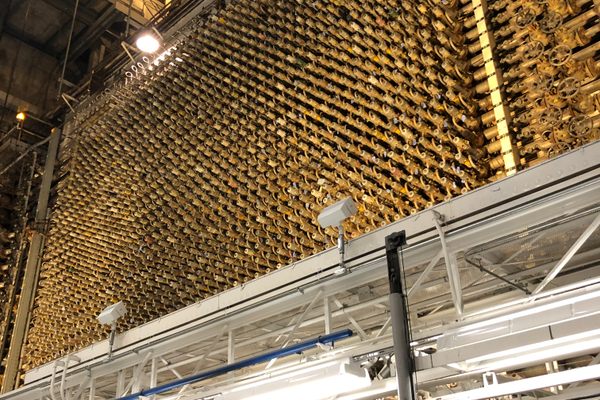

In southeastern Washington, drivers stopped their cars when strong wind sent the tumbleweeds soaring along State Route 240, which winds across the state toward Seattle. The area is wide and flat, and tumbleweeds aren’t uncommon there. (It borders the vast Hanford Nuclear Reservation, where the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built a 1940s plutonium facility that displaced 1,500 people and helped fuel an atomic bomb.) These tumbleweeds were especially troublesome, and whipped around like big, dry snowflakes. “It’s just like what we can envision in a white-out blizzard,” says Chris Thorson, a trooper with the Washington State Patrol, which fielded emergency calls from drivers. “People stop because it’s dangerous to keep driving at 60 miles an hour when you can’t see anything.”

The drivers braked, but the tumbleweeds kept coming, and they quickly blanketed the road and piled up between the cars. Within 30 minutes, vehicles were “completely encased,” Thorson says. The tumbleweeds gathered along a strip of road roughly the length of three football fields, and some heaps reached 20 feet high, Thorson says, tall enough to swallow an 18-wheel semi truck.

Massive drifts of tumbleweeds have accumulated from time to time in South Dakota, Colorado, and elsewhere, the New York Times reported, typically when a slew of plants are at the same stage in their life cycle and a strong wind knocks them free. “We get calls of tumbleweeds across the highway every year,” Thorson says—but over the two decades that he has worked this stretch of road, this is the first time he’s ever seen a pileup that completely blocked the highway.

Drivers couldn’t safely make a run for it, Thorson says, because the prickly plants were flying around in winds that rushed by at 40 or 50 miles an hour. The spiny spheres were sharp enough to scrape paint from cars; road crews had to pull on thick work gloves to protect their hands. “If you car is covered in it, you can’t just meander out of there,” Thorson says.

Twenty miles of the road were shut down for about 10 hours while crews cleared the tumbleweed-strewn section with snowplows. Thorson says that it wasn’t feasible to burn the tumbleweeds or feed them into a wood chipper: It was a chaotic scene, he explains, and attempting to incinerate them could have sparked fires. Instead, the trucks lofted the tumbleweeds into the air, and waited for some natural assistance. “You throw it up in the air, and the wind will take it,” Thorson says.

Tumbleweeds are great at spawning more tumbleweeds—a single specimen of Salsola tragus can produce as many as 250,000 seeds, according to the Washington State University College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences—and the seeds loosen easily. “When I go out and collect seeds for my research, I just put a paper bag underneath the plant and shake it, and that releases a lot,” says Shana Welles, a plant evolutionary ecologist at Chapman University who has studied tumbleweeds. Because tumbleweeds are such prolific reproducers, researchers sometimes take steps to keep their numbers down. When Welles grew some especially hardy species in an experimental garden, she and her collaborator killed them before they had a chance to roll away. “If you have a large number of large plants, it wouldn’t be hard to get to a million seeds,” Welles says.

If you do happen to find yourself snowed in by tumbleweeds and struggling to see the road, your best bet is to do pretty much exactly what these motorists did, says Thorson. Pull over, activate your hazard lights, call for help, and hunker down. It’s true for any inclement weather that winter might throw your way, Thorson says, “and it rings true for tumbleweeds.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook