Victorian Culinary Trading Cards Are a Feast for the Eyes

But maybe not for your stomach.

In 1983, Nach Waxman sought to stock his new bookstore, Kitchen Arts & Letters, with curiosities that weren’t cookbooks. He soon discovered Victorian-era advertisements known as trade cards. “I thought it would be a really interesting item to have in the store,” he says. “They’re attractive images and they’re small, so people could frame them, put them in their room, and put them on their kitchen walls.” The one problem? People weren’t buying them. Only one person was sold: Waxman. “I was hooked,” he laughs.

Before collectors clamored over baseball cards, Victorians couldn’t get enough of trading cards. The middle and upper class had a penchant for collecting the cards, which often came packaged with the products they advertised, and pasting them into scrapbooks. The name “trading cards” is thought to come from the phenomenon of collectors exchanging these cards, which advertised baking powder, Heinz tomato soup, and everything imaginable with images of chefs emerging from giant pickles and poetry-spouting pigs. Collectors such as Waxman refer to them as trade cards, to denote the term used at the time.

Today, antique trade card dealers often excavate the cards from old scrapbooks and sell them to aficionados like Waxman. “They’ve been up in somebody’s attic and not on very good paper, and what [the dealers] do is they lovingly soak the cards off, because some of them were glued in,” Waxman explains. “They soak the cards off the pages and press them flat, and do other things to make sure that they don’t lose their color.”

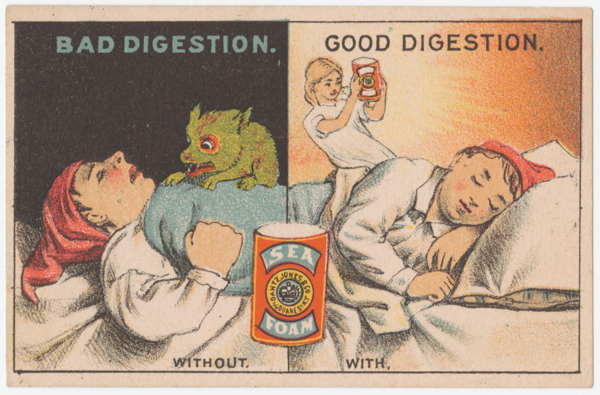

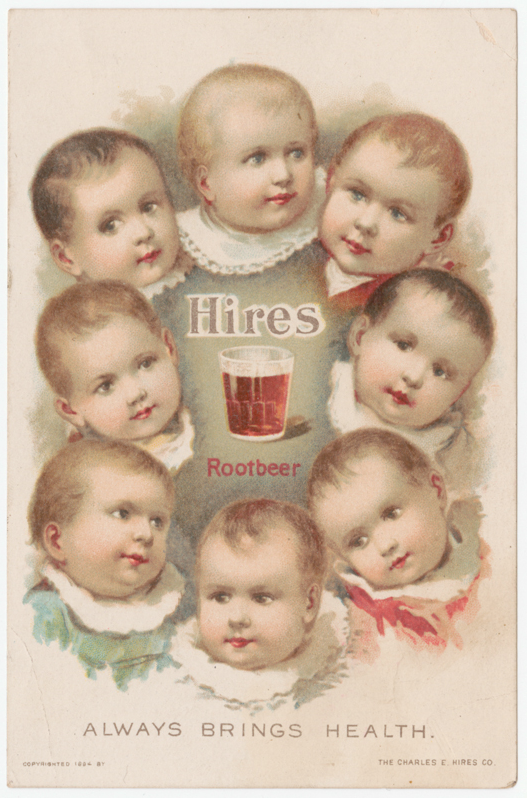

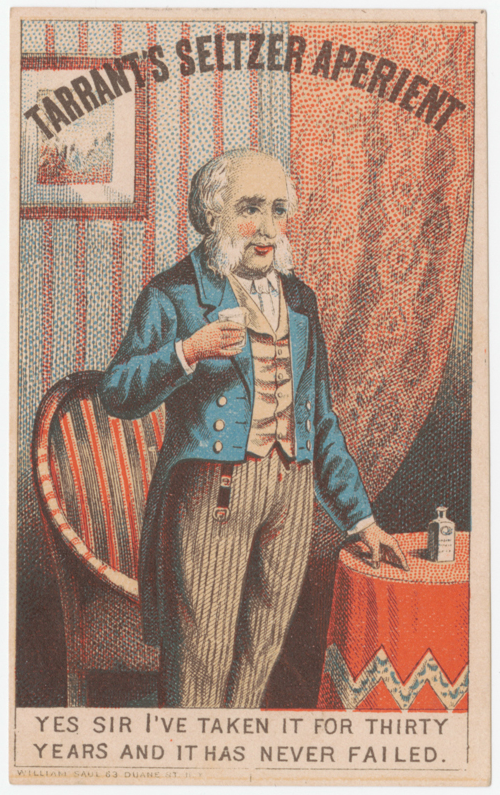

In 2015, Waxman gifted his cadre of trade cards to Cornell University, his alma mater. A new exhibition at Cornell Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections features around 6,500 trading cards, all of which depict the idiosyncrasy of the Victorian era. “The only word I can use for this collection is that it sprawls,” Waxman says. Part of that sprawl includes hordes of “medicinal” foods and drinks, which claimed to cure ailments ranging from drunkenness to diphtheria. The card for Hires Root Beer, depicted here, swore that it “purifies the blood.”

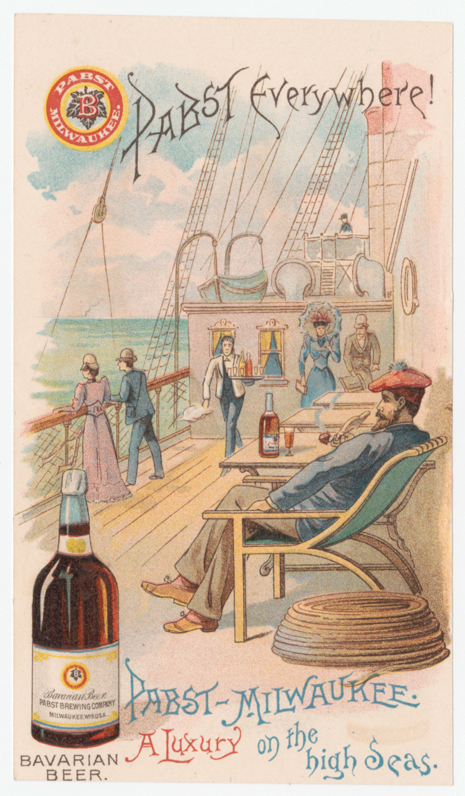

The trade cards are hardly limited to health, though. For these emerging leisure classes, they also offered the promise of mobility, such as this Pabst beer ad depicting “luxury on the high seas.”

Victorians loved highbrow culture, too. So advertisers liberally borrowed from artists, poets, and literary works. Which is why the face of Rembrandt, who died in 1669, graced a trade card for Enterprise Baking Powder.

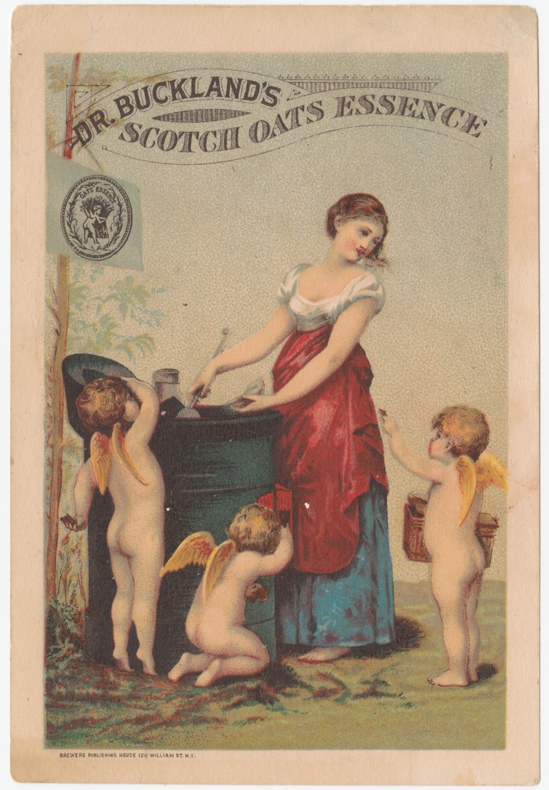

One remarkable technological advancement contributed to trade cards’ popularity: color printing. You see this in the advertisement for Dr. Buckland’s Scotch Oats Essence, which promises to cure drunkenness, paralysis, opium habit, sciatica, ovarian neuralgia, and epilepsy. In addition to claiming it’s a cure-all, the trade card incentivizes customers to send in a label from the package to receive a print “beautifully done in 15 colors” of the actress Lillian Russell. “They were colorful in a time when color printing was actually rather scarce,” Waxman says. “I mean, you couldn’t open up a copy of the Ladies’ Home Journal and find color ads. At most, they were two color.”

Ironically, trade cards fell out of fashion when magazines started printing color advertisements. Another kind of trade card—baseball cards—soon usurped their popularity, too. “As the interest in trade cards declined, the collecting fad diminished,” Waxman says. “It’s funny, they practically disappeared from sight.” Trade cards may have vanished altogether had it not been for the bubble gum business. “The only way that people even had a sense that there were such things as trade cards is because bubblegum manufacturers continued to put baseball players into their packages,” he says.

The Cornell University Library is displaying more of Waxman’s cards in an online exhibition. As you browse, try imagining which items that you’ve collected could end up in a museum one day.

*Update 11/02: This post has been updated to reflect that collectors refer to these cards as trade cards.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook