Photographers Take on the World’s Walls, Borders, and Barriers

An exhibit documents the obstacles we erect, and how we overcome them.

The Cold War was long, but by many accounts parts of its end—namely, the fall of the Berlin Wall—felt rather sudden. At a press conference on November 9, 1989, an East German government spokesman surprised everyone, including himself, when he announced that private travel would be allowed through border gates between East and West Germany, effective immediately. No one had told border guards, such as Lieutenant-Colonel Harald Jäger, as people started amassing at crossings. Jäger told Der Spiegel in 2009 that he had spoken with commanding officials, but there were no clear orders from above. Jäger said, “ … people could have been injured or killed even without shots being fired. In scuffles, or if there had been panic among the thousands gathered at the border crossing. That’s why I gave my people the order: Open the barrier!” And that was the beginning of the end for one of the modern world’s most famous walls.

The 30th anniversary of the opening of the Berlin Wall helped inspire the exhibition W|ALLS: Defend, Divide, and the Divine at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, according to Jen Sudul Edwards, who curated the show. With more than 70 artists and photographers participating, it presents a rich range of how dividers are portrayed—and it’s not all simply about architecture. “A wall for us is any type of barrier—emotional or physical,” says Edwards, who is chief curator at the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. The photographs portray how people are constrained by or resist walls and barriers, even when they are not visible. In one photograph, by SHAN Wallace, hands connect despite the separation of the rest of the bodies. In Raymond Thompson Jr.’s image of teenagers playing basketball at a juvenile detention facility, the metal fences around them are just one of the barriers they will face. Photographer Carol Guzy captured the moment at a refugee camp in Albania when a child was handed through a barbed-wire fence to relatives.

Edwards shares how the show was conceived, the future of walls, and some of her favorite images from the show. The exhibition is on view until December 29, 2019.

What inspired the theme for this show?

Katie Hollander, the director for the Annenberg Space for Photography, brought the idea to me. She realized that, as we approached the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we were seeing, hearing about, and obsessed with walls dividing nations more than ever before in our lifetime. As we started to do the research, we found out that this was, in fact, true. When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, there were 30 walls dividing nations, and when W|ALLS opened, the number was 77 and rising, with over a third of the world’s nation-states defining their borders with a barrier.

How did you select photos for the show?

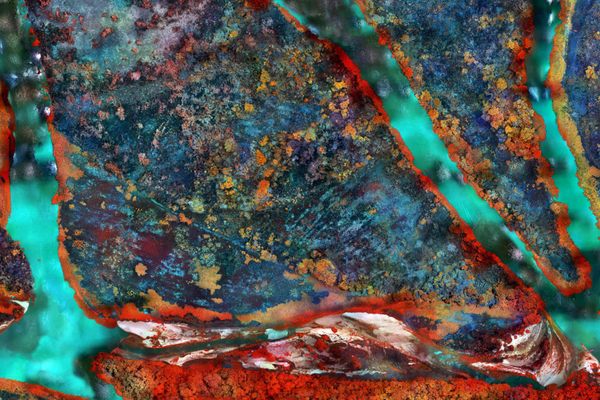

Broadly speaking, we sought to include as many regions and time periods as possible. We hoped to have all seven continents represented—we ended up with six—and both natural and human-made “walls.” Each photo had to refer to a barrier, but it also had to be poignant, whether that was because the image itself was beautiful or because it hinted at a story or revealed a narrative.

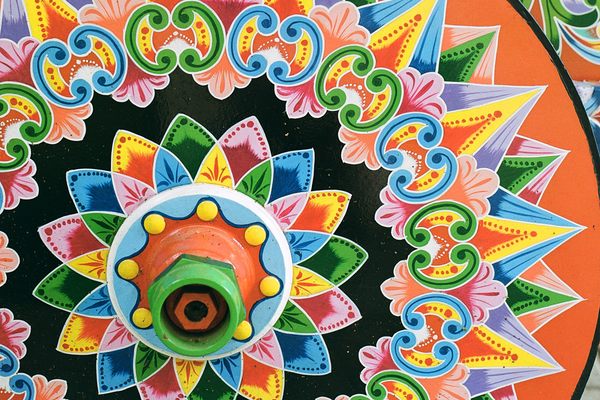

Ultimately, we organized the show into six categories—delineation, deterrent, defense, decoration, the divine, and the invisible—because we felt they covered all the reasons humans erect such barriers.

What conversations are you hoping the photos will provoke?

I hope that people recognize that walls are a human response to conflict and anxiety, not just a local, national, or contemporary issue. I also hope that the photographs prompt people to think about why we erect barriers, and to what end. Are they solving a problem or are they just a way to postpone dealing with true conflict? Finally, I want people to recognize the multivalent, morphing nature of a wall’s meaning—its function and significance changes over time and depends on who interacts with it. Police can erect a barrier to control a crowd and the crowd can, in turn, graffiti messages of protest onto that barrier. Who does that barrier belong to? Who is controlling whom and what?

What was most challenging about putting the show together?

I very much wanted the show to maintain a level of objectivity—or, at least, to present the whole issue and not just one side. I fundamentally do not believe that people can divorce themselves completely from their experiences, but I tried to stay as even-keeled as possible, as I wanted people from all different positions and perspectives to feel like they could experience the show openly and thoughtfully.

Is there an example where walls play a positive role in our society?

I think there are many. In her series on the 8-Mile Wall in Detroit, SHAN Wallace came to see that wall defining and uniting a community. I think that can definitely happen. Walls can also be powerful sites of meditation and remembrance. There are a number of memorials that represent that beautifully, and Candy Chang and James Reeves’s meditation walls Light the Barricades [on view outside the Annenberg Space] absolutely offer us that gift.

What roles do you think will walls play in our future?

Unfortunately, every year economic inequity becomes more pronounced and climate change converts more regions into inhospitable, untenable terrain. As long as that continues, people will see barriers as the only way to protect their space and their sovereignty.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook