Want to Make America More Inclusive? Start With Stamps

A group of black philatelists is making stamp collecting less stuffy.

Stamps from around the world. (Photo: Simon Davies/CC BY-SA 2.0)

When attendees walk into the World Stamp Show, a collectors convention held somewhere in the U.S. every 10 years, they’re greeted by a massive sign that reads, “The whole world is here!”

This isn’t an exaggeration: from May 28 to June 4 this year, collectors, traders, dealers, and stamp societies from as far as Egypt and Thailand convened at the sprawling Javits Center in midtown Manhattan. But despite the World Stamp Show’s global aspirations, walking around the space, the homogeneity of most of the attendees stood out.

“The stamp collecting community basically is synonymous with old white guys,” says Don Neal, the newsletter Editor in Chief at ESPER (Ebony Society of Philatelic Events and Reflections). ESPER, founded in 1988 and named after its creator, Esper G. Hayes, set out to change that limiting definition. Hayes, a stamp collector, met the black Olympian Jesse Owens a stamp show in the ‘70s, where she waited in line for his autograph. They were the only two black people at that show. After a solemn handshake, she pledged to Owens that she would do something to help African-Americans in the philatelic community.

In reaction to Owen’s death in 1980, Hayes made good on that promise: ESPER’s global society is now 28 years old and 300 members strong. It hosts booths at stamp conventions around the country, supports youth organizations, convenes social events and provides a network for African Americans in philately.

ESPER members at a 25th anniversary event in 2013. (Photo courtesy of Don Neal)

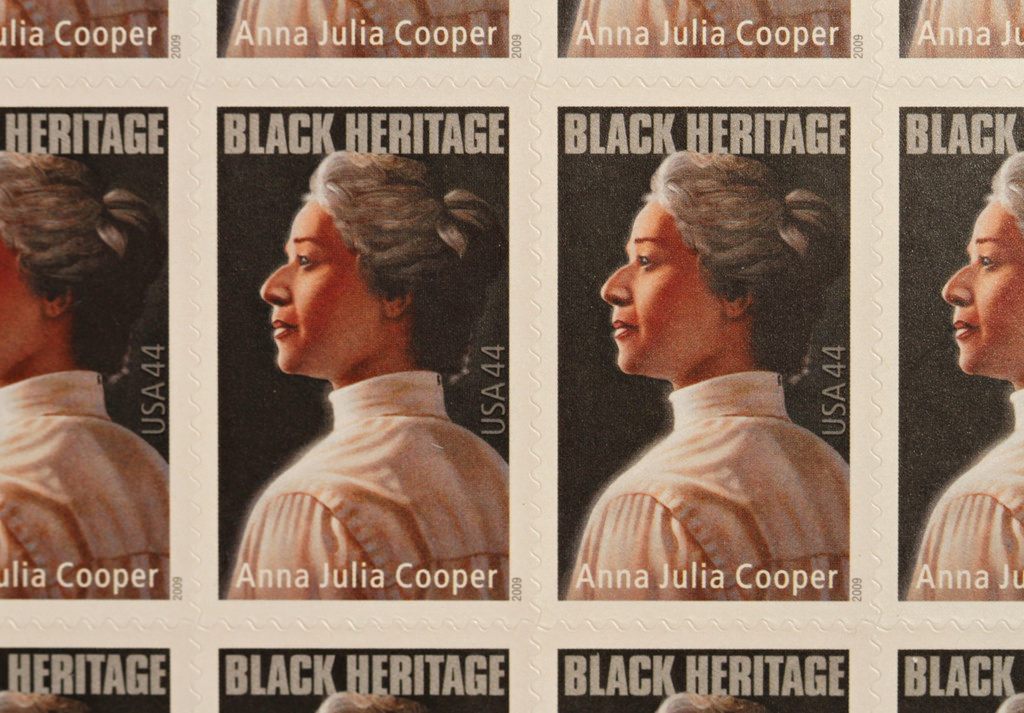

Though today ESPER is thriving, its existence was only made possible in the late ‘70s. The first African-American to appear on a stamp was Booker T. Washington, in 1940, nearly 150 years after the first US postage was issued. It would be 16 years before another black person appeared on a stamp. Finally, in 1978, the United States Postal Service launched the African American Heritage Stamp program, an effort to place one important African-American figure on a stamp every year, something they’ve continued to this day. Those featured include everyone from political figures like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. to artists like Louis Armstrong and Langston Hughes.

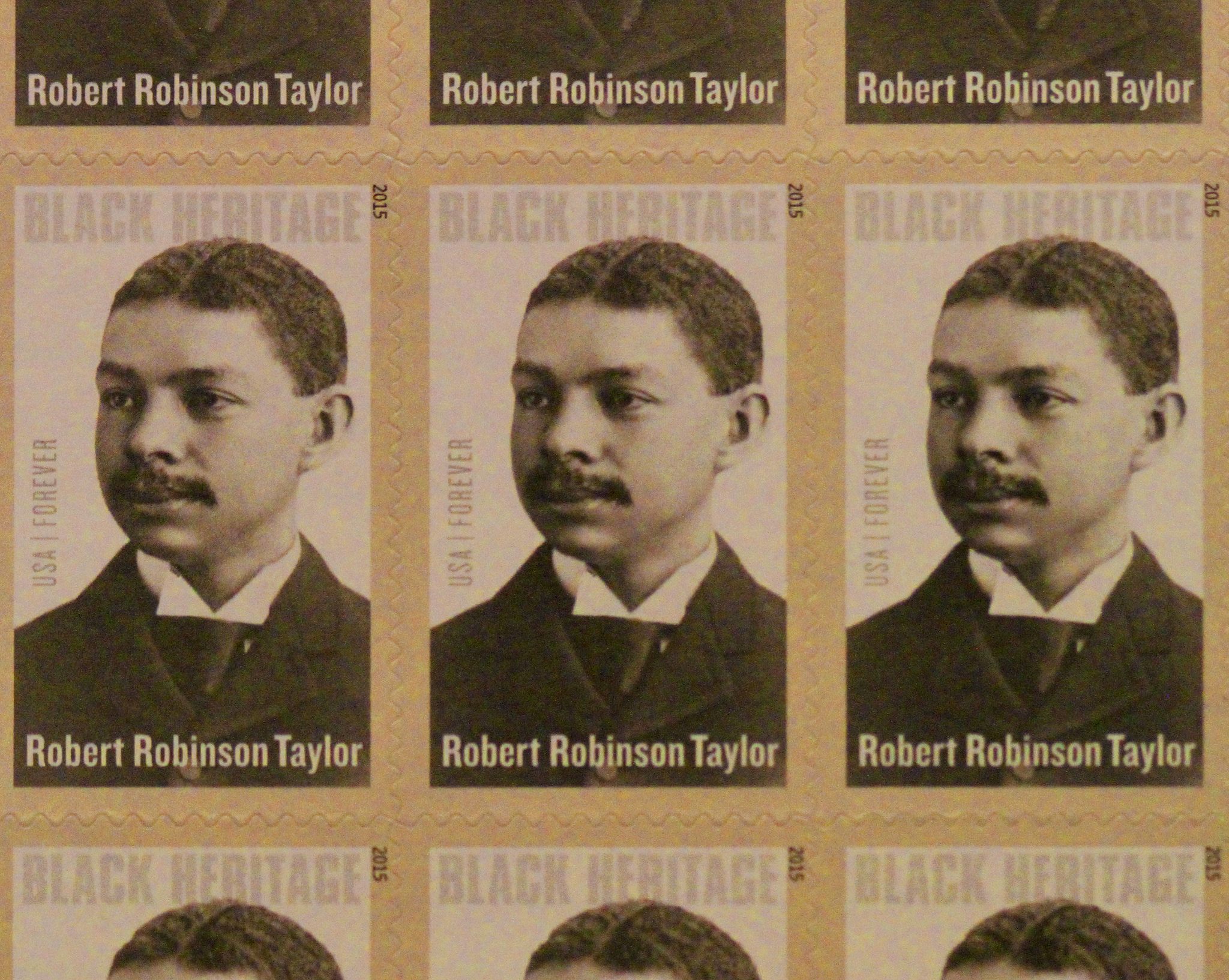

The initiative drew many African-Americans into the philatelic community, but it’s also alienated some white stamp collectors. The influential stamp collecting magazine Linns conducts a poll every year, asking subscribers to vote on their favorite and least favorite stamps issued that year. “[Typically,] the stamp voted ‘Most Unnecessary Stamp’ may not be the Black Heritage stamp, but it’s going to be a stamp of an African American that year,” says ESPER president Walter Faison. In 2015, the stamps featuring Maya Angelou and the black architect Robert Robinson Taylor both ranked highly in the “Least Necessary” and “Worst Designed” categories.

The Robert Robinson Taylor stamp, issued in 2015. (Photo: John Flannery/CC BY-SA 2.0)

An event like the World Stamp Show, which by nature brings people from all over the world together, can be a more welcoming environment for ESPER than the shows that only allow US-based societies. “You have a lot of people here from different countries who recognize that, at least while they’re here, they are a minority. Who do they connect with? A lot of times they gravitate to us,” Faison says.

“Canada has started its own Black Heritage series, where they recognize people of African descent that have made contributions to Canadian history. Israel has stamps out with African Americans on them, Poland, Norway, Sweden,” Neal says. “It’s not just about America, it’s a global thing. It makes the world a little smaller and shows that we have more in common, perhaps, than we have in terms of differences.”

Internationally, stamps are generally treated with a little less gravitas than they’re granted in the U.S. Here, living people can not appear on stamps. The rule used to be that a figure must be dead for 10 years before they could be put on a stamp. That was later changed to five years, and now people can appear on stamps immediately after their death (except for presidents, who traditionally appear on the anniversary of their first birthday after their death).

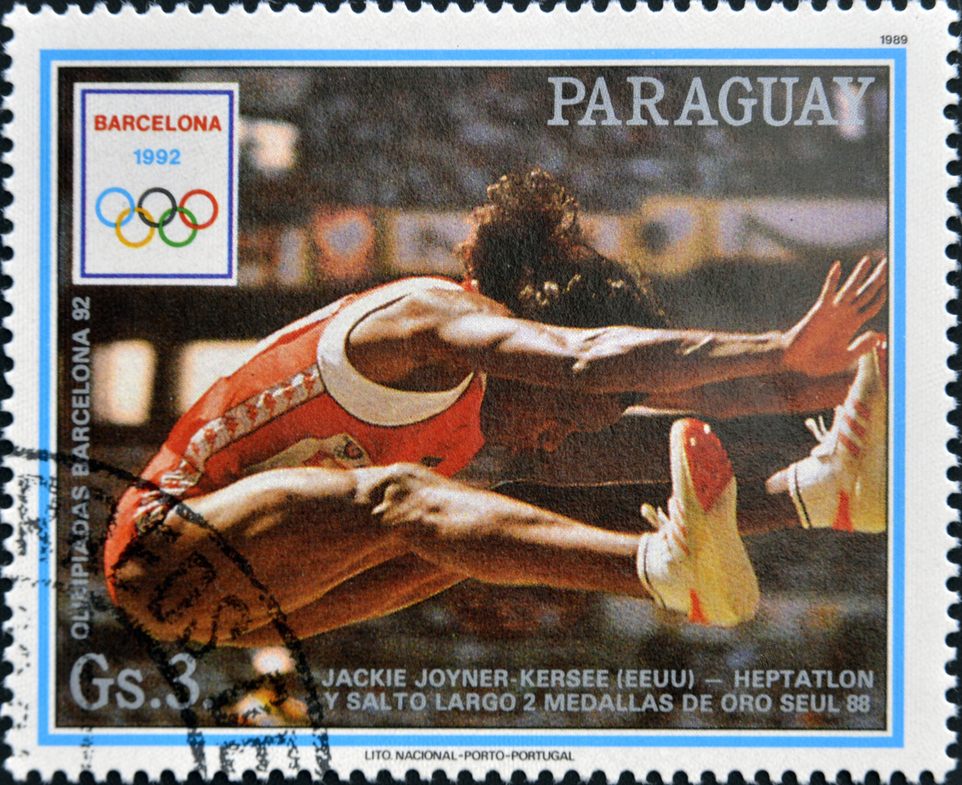

For black stamp collectors, that means the pool to draw from is limited. Due to slavery and post-slavery discrimination, most African-American figures regarded as important to US history lived in the 20th century, and many are still alive today. As collectors, many ESPER members look outside the U.S. to find stamps that suit their interests, including the many honoring Barack Obama which have been issued by countries around the world.

A stamp honoring American heptathlete Jackie Joyner-Kersee, issued in Paraguay in 1989. (Photo: Public Domain)

Both Faison and Neal were emphatic in their description of ESPER as a welcoming and pluralistic group. “We’re a very engaging society. We have fun,” Neal says. “Of the smaller societies we are, without a doubt, the most diverse.” Not all ESPER members are black. Of those from non-African-American backgrounds, most are interested in a specific genre of stamps that happens to align with black culture, like jazz. One of their members is a white woman from New Zealand who stumbled upon their booth in a hotel and ended up writing her PhD thesis on black jazz musicians on stamps. She stopped by to visit during the World Stamp Show.

In a world full of Oculus Rifts and hoverboards, getting young people interested in static pieces of paper no bigger than a QR code can seem like a tall order. But ESPER is set on initiating a new generation into the world of philately. Neal says he hopes to draw young people’s interest by appealing to whatever they like already, be it Star Wars or basketball. He buys “yearbooks” for kids he knows, the name for a collection of all the US stamps released the year they were born. ESPER also sponsors a Boy Scout team in North Carolina, who, in 2016, can still earn merit badges for stamp collecting.

Even if teenagers and young adults continue to see philately as the domain of nerds, that doesn’t mean they won’t warm to the idea later in life, say Neal and Faison. Both men say they collected as children, lost interest for a while in young adulthood and came back to the hobby in middle age. “You get to a point where you’re too sophisticated to collect stamps,” says Neal. But young do collectors exist. “We have a young lady from Brooklyn who is 14, I think. She’s a member. She joined at a New York show maybe six months ago. She came here and showed the collection, and everyone fell in love with her,” Faison says.

Stamps honoring Anna Julia Cooper, an author, educator, and the fourth African American woman to earn a PhD. (Photo: John Flannery/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Neal also believes that keeping the hobby alive depends on those who make decisions about US stamps adapting to the times.“We’re just so worried. In other countries, Olympic athletes have been put on a stamp, and then you find out they were dope users. It is very embarrassing to the country, so we don’t want to do that. God forbid the United States should be embarrassed,” Neal says with a hint of sarcasm. “I’m not opposed to having Bart Simpson on a stamp, or Harry Potter on a stamp. They don’t always have to be dead historical people,” says Neal. The aim is for greater diversity—both on the stamps themselves and among collectors. “You need to see it in the exhibits, you need to see it in the societies.”

It may be that ESPER itself, with its passionate members, global focus, unique demographics, and open minds, is American philately’s best hope for the future.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook