These Cheeky Statuettes Were Part of Edo-Era Japan’s Answer to Pockets

Ornate netsuke were practical status symbols.

Sixteenth-century Japan had a wardrobe problem. Citizens of every class all wore kimonos, T-shaped robes wrapped around the body and held in place with sashes called obis. Kimonos are functional and elegant but lack a crucial element rather helpful for everyday life: pockets. People have always needed to carry things, and medieval Japan was no exception. The practical solution to this sartorial problem evolved into netsuke, one of the most distinctive and diminutive art forms in a country known for them.

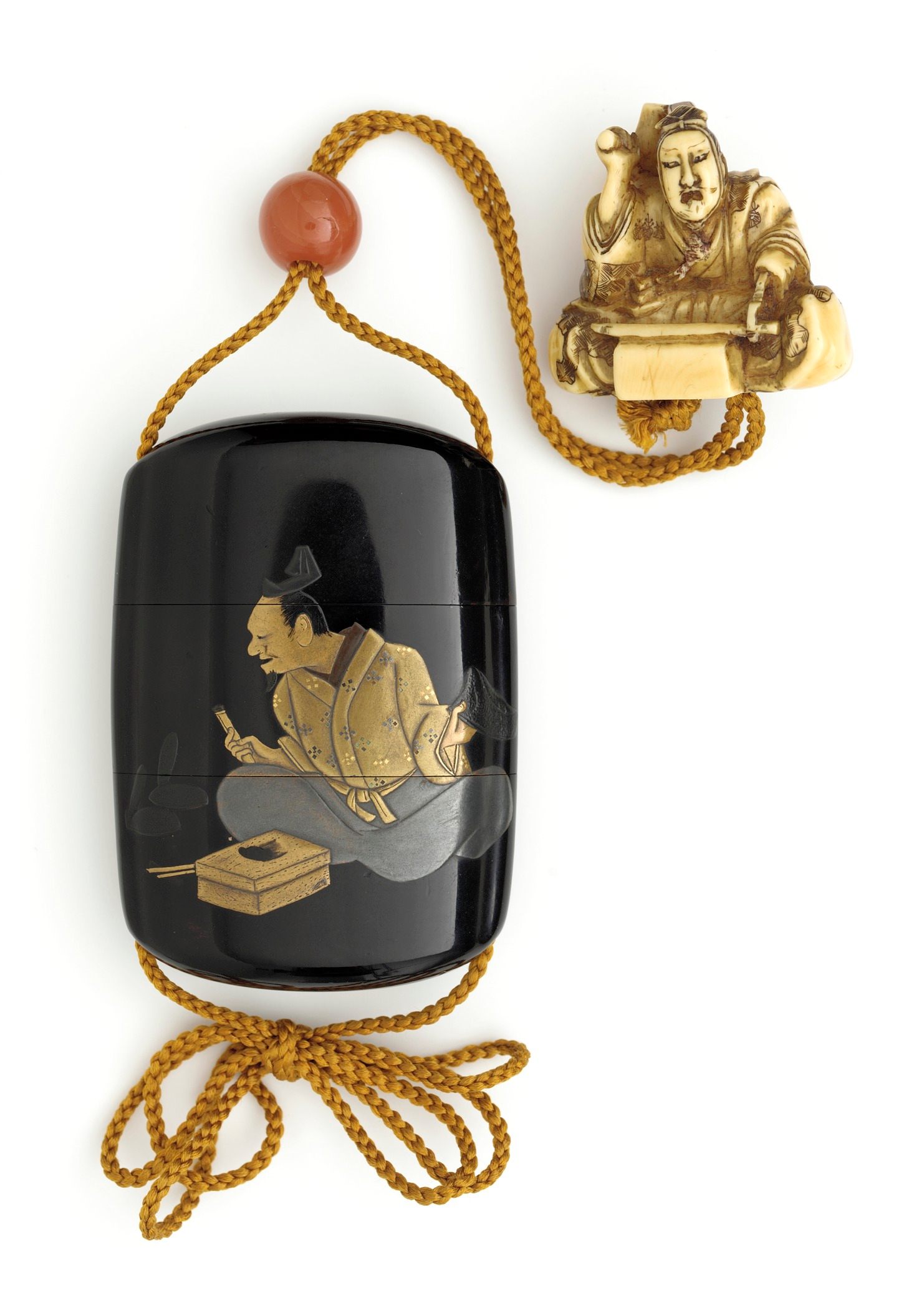

Netsuke were, from their creation, a gentleman’s game. Japanese women made do by tucking small objects into their baggy, sewn-up sleeves, creating a kind of makeshift purse, Hollis Goodall, a Japanese art curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, told Christie’s. But men had no such luck, with their open, unsewn sleeves. To carry small objects such as tobacco or medicine, they crafted sagemono—generally, “hanging things”—that were suspended on a cord from an obi. They functioned like detachable external pockets or tiny purses, and to keep them in place, men fastened small carved ornaments, netsuke, to the loose end of the cord. The totems acted as counterweights that helped cradle the pockets between the wearer’s waist and hip. “It’s like a fob or a toggle, a giant button,” says Robert Mintz, deputy director of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and a scholar of Japanese art. “You pop the giant button under your belt and it keeps your suspended object from falling.”

The first netsuke were observed during the 16th century, in Japan’s Muromachi Period, and were simple, natural paperweights, frequently a chunk of wood or a dried gourd, Japanese netsuke expert Barba Teri Okada wrote in a 1980 issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. After all, any small object could work. The only requirement was that the item must have a place to thread a cord and be smooth all over to avoid snagging on the delicate silk of a kimono. But the artistic possibilities of the ornaments were endless, and Japan’s evolving social structures led artists to transform these mundane objects with an entirely new class of craftsmanship.

The first to wear netsuke were warriors, or at least men from the warrior class. When shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu ascended to power in 1603, he instituted stringent neo-Confucian code that stratified society into four distinct classes, Okada writes. Warriors were at the top, followed by farmers, artisans, and finally lowly merchants. The shogun established laws to govern seemingly every aspect of daily life, including sumptuary laws to dictate how people were to dress, Japanese art scholar Terry Satsuki Milhaupt wrote for a netsuke exhibit she curated at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. For example, as members of the highest class, samurai were allowed to wear two swords as symbols of their rank. But Japan was in the midst of a luxurious, 300-plus-year period of peace, and samurai soon began to spend their money elsewhere. They began carrying fancy pillboxes called inrō, which, like any hanging thing, required a counterweight and anchor.

But in the 17th century, netsuke shifted from functional items to must-have accessories, when they became part of a widely spreading addiction. The Portuguese had just introduced tobacco to Japan, and pipe-smoking became a new craze. Many Japanese men carried tobacco and a lighter on their person at all times, stoking demand for yet more netsuke, Okada writes. The items had also become status symbols for a newly rich and ascendant merchant class that sought to flaunt wealth without breaking sumptuary laws, Milhaupt writes. Though the shogun passed an edict forbidding the use of tobacco in 1609, the law was repealed in 1716 in the hope that tobacco production would help lift the economy. It did.

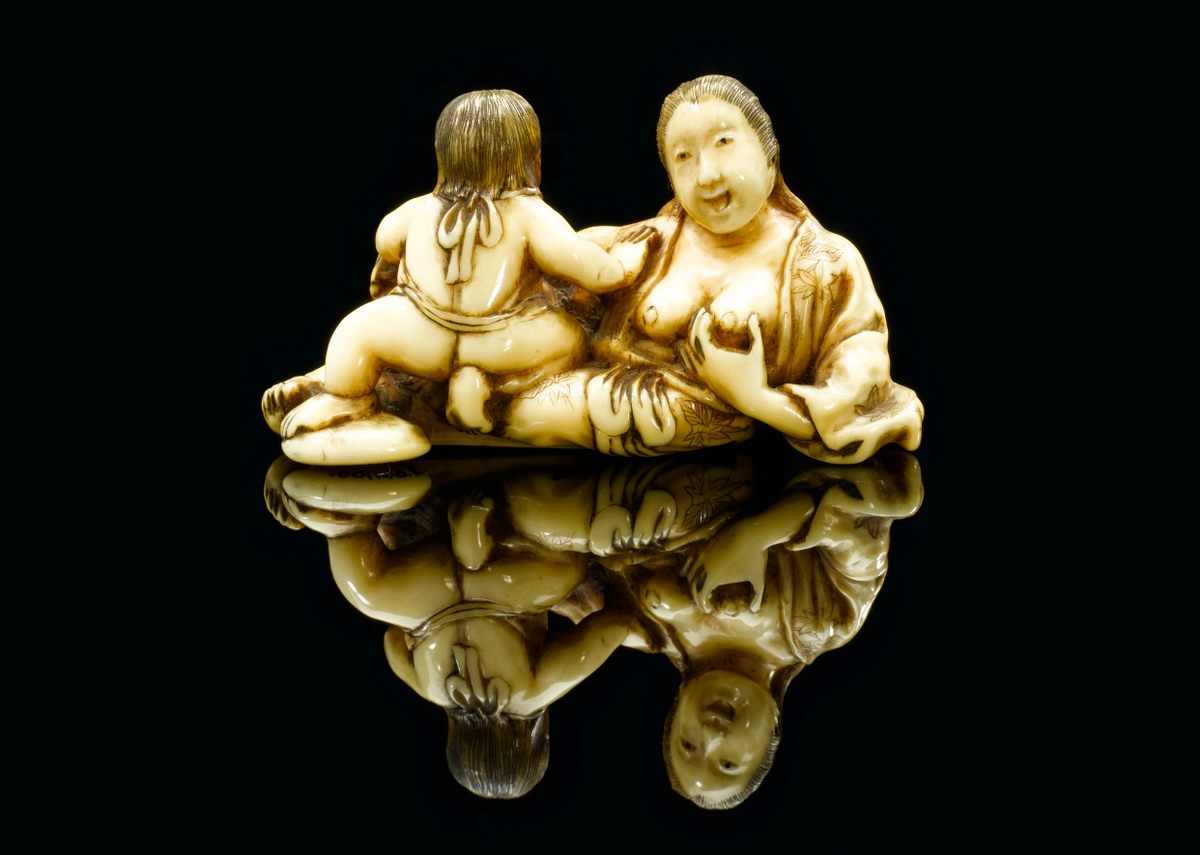

Netsuke carving had grown from a hobby of traditional artists such as mask carvers or sculptors into its own form. Artists began to specialize in netsuke and developed their own schools and styles. In Shimane Prefecture, carvers of the early and celebrated Iwami school never made the same netsuke twice. Netsuke, as a form of art, grew into political and social commentary that seemed to escape the watchful eyes of the government. Craftspeople began to carve objects satirizing leadership or expressing subversive religious thoughts and feelings, Okada writes. Some even veered into the ribald, conveniently small enough for any grotesque or erotic theme to be unnoticed by a passing Tokugawa military authority, according to Milhaupt.

But netsuke came in many forms, Okada writes. Most common were the tiny sculptures known as katabori netsuke, three-dimensional carved figures. But there were also anabori netsuke (hollow trinkets carves from clams), ryusa netsuke (discs so intricately carved that light could pass through), and mask netsuke, which resembled tiny theatrical masks. Certain netsuke led elaborate double lives, perhaps as an ashtray to catch smoldering ashes from a gentleman’s pipe, or as a compass. Other historical examples functioned as whistles, sundials, abacuses, brush rests, and even firefly cages. There were even trick netsuke, crafted out of mundane moving parts that would open to reveal a surprise, such as a tiny goddess nestled between two halves of a nut.

According to Okada, the most common netsuke depicted figures from Japanese and Chinese legend, such as the shishi (lion-dog) or the creatures of the zodiac. Human-shaped netsuke were rarely heroes, but rather characters from folklore or kabuki actors, which could be rendered in far less detail but remain recognizable. At the dawn of the 19th century, netsuke began to reflect scenes from everyday life, such as ordinary townsfolk doing daily chores.

The most status-granting carvings were made from any material considered rare. While many were carved from ivory, artists also experimented in wood, amber, antelope horn, persimmon, boxwood, narwhal tooth, boar tusk, hornbill beak, and many other mediums,art collector Anne Hull Grundy wrote in Netsuke Carvers of the Iwami School.

As netsuke become flashier and more intricate, it no longer was enough to just have one fancy example. The flashy and stylish began wearing season-specific netsuke, and it was highly unfashionable to wear one at the wrong time of year. “If someone wears a chrysanthemum and it’s not an autumn month, you’d say, ‘Oof, why is he wearing a chrysanthemum?’” Mintz says.

The golden age of netsuke art arrived at the beginning of the 19th century, according to Contemporary Netsuke by Miriam Kinsey. Professional carvers abounded in major cities, and to prove their prowess, true masters might etch entire poems on the bottom of the figurines, which could only be read with a magnifying glass. As certain carvers became famous, Mintz says, sneaky, less-accomplished carvers might forge the name of a great on their own substandard creations. “There are a few famous carvers whose names were used over and over, even after they died, because they were popular and famous,” he says. “But the crude ones are still really kind of charming.”

If netsuke’s rise in popularity was always tied to tobacco, so was its fall. When Commodore Perry landed on Japanese shores in 1853, foreign trade reopened for the first time in over two centuries, Okada writes. Japanese men began dressing in Western clothing—styles notoriously packed with pockets—and replaced small-bowl pipes with cigarettes, which eliminated the need for a tobacco pouch.

Netsuke disappeared as a functional item and status symbol, but found a second life as collector’s items. People from the United States and Europe grew fascinated by the intricate miniatures and began acquiring them, Kinsey writes. This passion persists today, with a subculture in collecting similar to the collector’s market for Japanese swords or snuff bottles. In the 21st century, the art of netsuke is far from forgotten. Today, many netsuke artists eschew ivory, in compliance with international bans on trading African elephant ivory, according to National Geographic. These contemporary netsuke makers instead opt for the plastic elforyn, or sustainable natural materials including wood, deer antler, metal, and stone.

Founded in 1975, the International Netsuke Society publishes a quarterly journal describing netsuke of note and spotlighting modern artists—many of whom hail from outside Japan—and workshops open to the public. Like kimonos, netsuke are still worn today, though usually not the vintage examples, which live in the cabinets of museums and dedicated collectors, as a distinctive national art form. “If you think of quintessential Italian art, you imagine frescoes or oil paintings, while the symbol of Japan is this tiny little goofy sculpture,” Mintz says. “I find that kind of amazing.”

The Kyoto Seishu Netsuke Art Museum is the only museum in the world dedicated to these tiny treasures. Housed in a beautifully restored two-story samurai residence, it specializes in contemporary work and displays around 400 figurines at a time, from an aviator penguin chick to beavers in love. While the museum displays the most intricate examples under magnifying glasses, it wouldn’t hurt to bring your own.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook