What Do You Do When You Find a Mammoth on Your Farm?

A behind-the-scenes look at harvest time, soil drainage, and Pleistocene megafauna.

Most mornings, James Bristle is up by 6:30. When the ground is frozen and the corn, soy, and wheat have all been harvested, maybe he can take a moment to sit and read the paper over breakfast. But not for too long. Bristle also raises Angus steer on the gently rolling farmland his family purchased in 1956. No matter how tired or cold he is—and Michigan winters are long and bitter—Bristle has to feed the herd, more than 100-head strong, and shake loose bales of straw for the cattle to bed down on.

Then there’s the paperwork to sift, or deliveries to shepherd, or seed corn to store for other farmers until the thaw. The land itself requires upkeep, too, on patches that are too dry or where water is pooling. Even in that narrow window when the fields aren’t full, Bristle’s schedule isn’t fallow; he’s crisscrossing the barns, toolshed, and bunker silos, or working some corner of the 585 acres.

That’s what he was doing, one day in 2015, when he struck a woolly mammoth with a backhoe.

That July Bristle had acquired some more acreage, and he was looking to take advantage of the slightly slower season to install tile to improve soil drainage. His next-door neighbor, Trent Satterthwaite, drove over with equipment—tractors, a backhoe, an excavator. (“Next-door is three-quarters of a mile away,” Satterthwaite says, laughing. “We’re out in the country.”)

They were about eight feet down into the earth when Satterthwaite spotted something vaguely white and mangled-looking. It reminded him of a fence post, warped from years in the damp soil. That wasn’t so odd, he thought—sometimes things have a way of sinking into the ground. So they kept digging.

In the next scoop of earth, Satterthwaite recognized something that looked “like an old tree stump.” He turned off the backhoe and got closer. As he peered at it, he detected a constellation of little honeycomb shapes and realized he was looking at bone. Partway through the project, idle equipment all around them, Satterthwaite looked at Bristle and said, “Man, we just hit a dinosaur or something.”

Bristle is no stranger to the remains of animals—he’s seen plenty of massive steers splayed out and butchered on barn floors. “I knew the bone we brought up was bigger than anything I’d ever seen,” he says.

But he wasn’t sure exactly what it was, or what to do with it. What if it was prehistoric? Decades earlier, while digging a pond, another local farmer had stumbled across parts of a mastodon—a jumble of vertebrae, ribs, tusk, and skull and jaw bones. Careful digging ensued, and went on for months, Satterthwaite recalls. The whole thing seemed like a lot of hassle. Bristle worried that a full-scale excavation could lead to troops of scientists tromping across the fields for ages, yanking up crops and eating into the growing season. “We didn’t know what kind of can of worms we were opening,” Bristle says.

And then there was the hole. If the farmers left it open, it could fill with water, undoing their work. The equipment sputtered back to life, and Bristle and Satterthwaite used concrete and a metal culvert to stabilize and seal the trench. Then they replaced the soil, tucking the bones back under a blanket of earth.

Twenty-thousand years ago, the Great Lakes region was covered in a sheet of ice. Then, retreating glaciers scoured the land, carving out space for countless lakes and rivers. Many, many animals lumbered across the Midwest during the Ice Age: Saber-toothed cats, ground sloths, mastodons, and mammoths lived among poplars and spruce trees. Traces of these enormous amblers have a way of turning up during construction projects, both large and small.

A number of fragments of mammoths, mastodons, and other megafauna have surfaced in Michigan just within the last few months. In September, one Michigan family found a pair of mastodon teeth. (They’d first encountered similar chompers—likely the same ones—several years ago, but lobbed them into the woods.) That same month, developers working on a housing complex on the other side of the state found pieces of mastodon bone.

Some discoverers are entranced by their finds, some hope fossils will make them rich, and still others decide to donate their hauls to science, says William Simpson, the collections manager of fossil vertebrates at the Field Museum in Chicago. Pieces of a giant beaver skull appeared while crews were digging the foundation for a public school, Simpson says. A fairly complete mastodon was unearthed when a farmer dug a stock pond. One local man found a mastodon jaw while working construction on an expressway southwest of the city in the 1960s, and stowed it under his porch for decades. Eventually, he gave it to his neighbor, Simpson says, and the bone is now on display in the museum’s Evolving Planet exhibition.

Though he doesn’t keep track of how many paleontological inquiries he handles, Simpson says it’s not uncommon for him or his colleagues to be asked to weigh in on some serendipitous find. The discoverer might email photos, or even just ship the find to the museum. For the past few years, the Field Museum has also hosted “ID Days,” when anyone who thinks they have a piece of prehistoric flora or fauna can bring it in for on-site verification.

“Three-quarters of the time, or more often, it’s not what they think it is,” Simpson says. A bone might actually date back decades rather than millennia—or maybe it’s not a bone at all. Simpson has seen a rock eroded in such a way that, at first glance, it appears to be a skull. “I can usually see what they see, why they’d think it’s a dinosaur skull or tooth or tusk, but it usually isn’t,” he says. “Without the experience of seeing lots and lots of different skulls, I’d probably be confused, too.”

Those who find fossils and turn to the internet for guidance might end up reaching out to James Kirkland, the state paleontologist of the Utah Geological Survey (UGS). The UGS published a guide called “What Should You Do If You Find a Fossil?” in 2009, and the agency is bombarded with fossil identification requests from all over the country—Kirkland estimates he gets at least one a day. People often preface their messages by declaring that they’ve made a “huge discovery,” Kirkland says. That’s rarely the case, but Kirkland does ask them to collect as much information as possible—such as extracting the metadata from an iPhone photo—to zero in on the precise location. He then points them to a local paleontologist. “We work for the state of Utah, so we’re only paid to work in Utah,” he says. “We need to get people lined up with someone in their area.”

On occasion, over his 45 years in the field, he’s referred someone to another paleontologist for an identification, an appraisal, or help with extraction, only to see the fossil disappear because the owner is trying to make a quick buck selling it. There’s not a whole lot Kirkland can do about that, since any fossil found on private land is the property of the landowner. Though many paleontologists and geologists would prefer to see objects wind up in museums or other repositories where they can be studied or used for teaching, that decision isn’t theirs to make.

“We’re begging when it comes to private land. ‘Please, sir, can I have some more?’” Kirkland says. “People think you’re going to shut ‘em down. [But] we have no right to do anything. It’s a total fiction that we have the right to go on to someone’s private property and tell them what to do.”

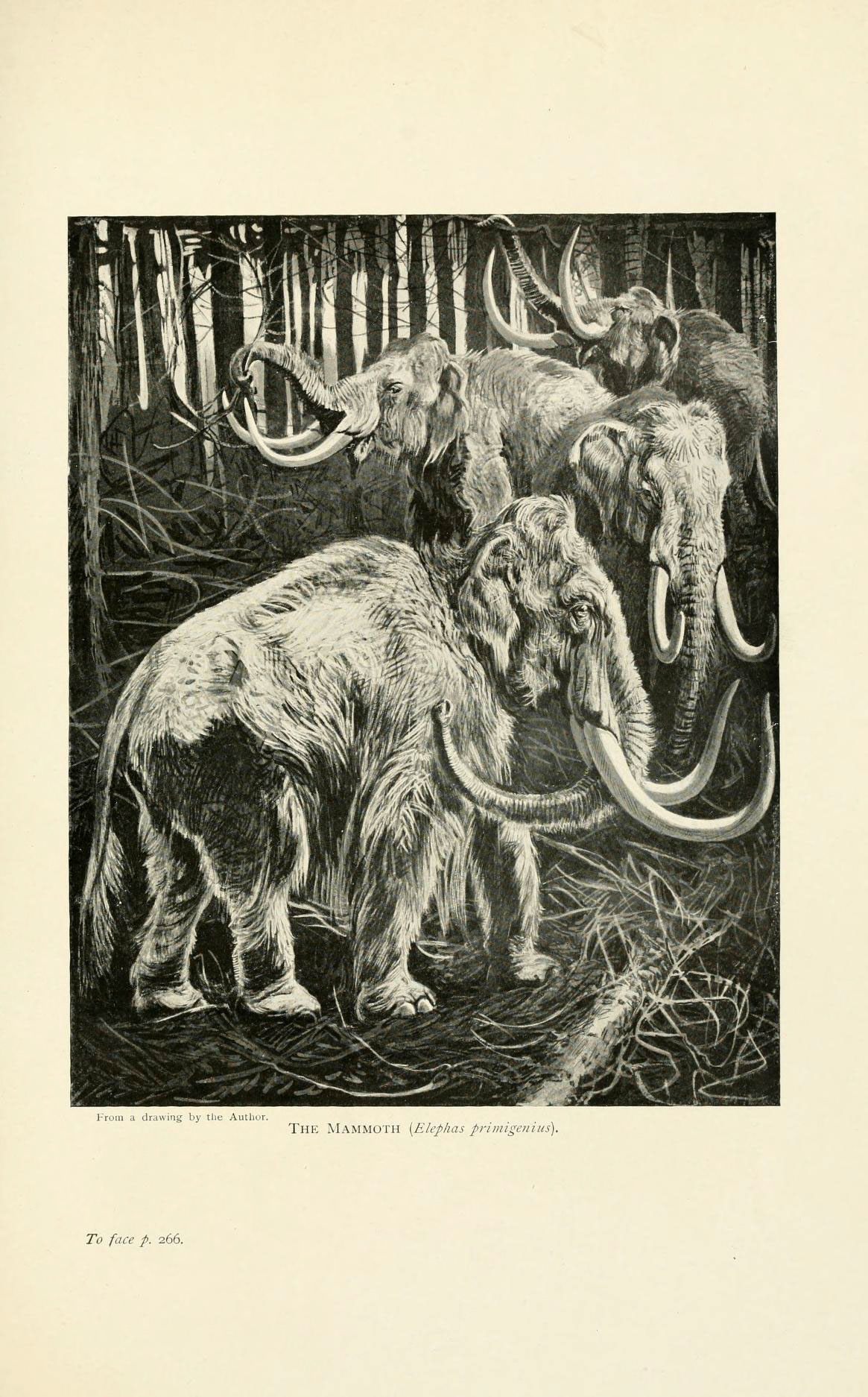

After a bit of Googling, Satterthwaite arrived at the same conclusion: In the United States, landowners have complete control over whatever they find in the ground. That assuaged Bristle’s concerns that experts would snatch the bones or wrest control of his land. Meanwhile, Bristle’s daughter pulled up a drawing of a mammoth on her phone, and his grandson went starry-eyed. “That’s what convinced me, ‘Let’s go ahead and dig,’” Bristle says.

Bristle and Satterthwaite reached out to Daniel Fisher, director of the University of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology, which is just 20-odd miles from the farm. Fisher, who has spent nearly 40 years in the field, said he’d swing by.

“I saw immediately that they had two pieces of a mammoth, the pelvis and shoulder blade,” Fisher says. Within 15 minutes, he’d spotted a smattering of other, less-conspicuous fragments mounded on the surface. “I said, ‘There’s quite a bit here. I’d be interested.’”

Bristle gave Fisher permission to dig, but with caveats: Any excavation had to wait until after the harvest, and Fisher had a single day.

Give the time constraint, Fisher and his team focused their digging. They uncovered nearly 60 bones, which Fisher attributed to a male mammoth and took back to the university for analysis. Radiocarbon dating placed the bones at around 15,000 years old, and there’s some evidence to suggest that early humans had butchered the massive mammal.

When the hubhub subsided and the scientists had left, Bristle refilled the hole and got back to work. He laid down more tile line and planted corn, then wheat. “By agreement with us, he did leave open one quadrant to the southeast,” Fisher says, just in case the preliminary research sparked enough questions to warrant a second dig.

For two years, Bristle planted and harvested atop where the mammoth’s bones had lain. That wasn’t a threat to the preservation of other, still-undiscovered remains, Fisher says. Most farm equipment is designed to exert minimal pressure on the sediment—otherwise, land would get compacted and drainage lines would get squashed.

Last month, Bristle allowed Fisher to return to the site for a two-day blitz of research and excavation. Fisher and his brigade of researchers collected samples of sediment and pollen, and recovered vertebrae and fragments of other bones. “We said we’d do it at a time that would minimize interruption to [his] work, and if we cause crop damage, we’ll cover that,” Fisher says. The team did bust up two tile lines, “and we’ll cover the cost of repairing those,” Fisher adds.

It is a solid skeleton, with a spectacular skull and tusks, but so far there’s no trace of its feet or the long bones of its limbs. “You always wonder about the things you don’t find,” Fisher said in a video produced by the university.

As gawkers descended on his farm during the digs, Bristle says, bystanders sometimes remarked that he looked nonplussed about the whole circus. Wasn’t he thrilled by the find? It’s not that he resented it, exactly, but the spotlight made him a bit squirrely, and he hadn’t been especially awestruck by the paleontology. “If I would have found the first steel-wheel tractor,” he says, “I would have been more interested.”

The whole thing “has been a little disruptive,” Bristle says, “but it was the right thing to do to dig and donate it.” Over time, Bristle has grown more interested in the Pleistocene, and the creature that trundled across his patch of tundra. His sister tucks all the articles and photos about the dig into a scrapbook, and he has a replica of one of the creature’s teeth.

He’s also rechristened his farm, too. On one of his red barns, Bristle has hung a metal sign bearing a colossal mammoth silhouette, alongside a nod to the elder generation of Bristles. “Mammoth Acres,” the sign reads. “Established 1956.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook